Alaska’s sick fish

Fayleen Peters Wiehl, 12, nets a salmon caught on the Yukon River in Tanana, Alaska. Native Americans and other subsistence fishermen who live in this tiny town about 700 miles inland rely on the migrating salmon for smoked and dried fish to get them through harsh winters. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Freshly caught salmon lie on the deck of Stan Zuray’s boat as it makes its way to the Zuray fish camp, about an hours boat ride up the Yukon River from Tanana. Zuray and his wife maintain the fish camp during part of the year to stock up for the winter. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Fayleen Peters Wiehl makes her way up the bank of the Yukon River to unload a backpack full of fresh king salmon fillets so they can be cut into strips for drying in the smokehouse. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

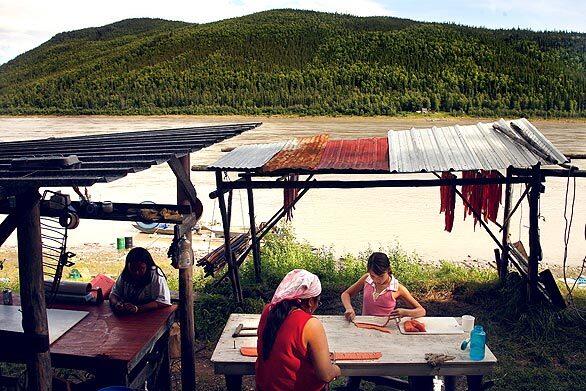

Faith Peters and Haley Brigham, 12, help Kathleen Zuray cut king salmon into strips at a fish camp on a stretch of the Yukon River called the Rapids. Eagerly awaited each year, king salmon are the biggest and most prized fish migrating upriver to spawn in the Yukons headwaters, in Canada. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

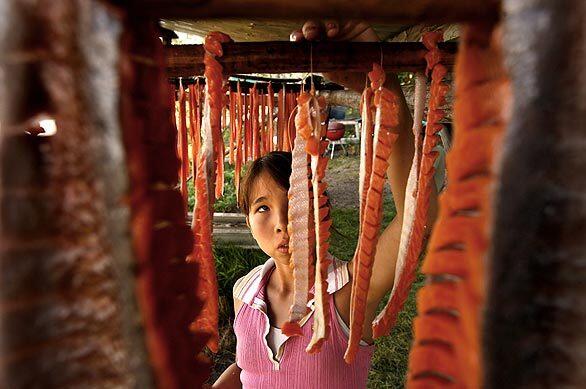

Haley Brigham helps hang strips of king salmon to cure for winter consumption. Drying salmon is a long-standing tradition among Native Americans and subsistence fishermen living along the Yukon River. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Fresh strips of king salmon hang in the smokehouse at Stan Zurays seasonal fish camp along the Yukon River. Once cured, the strips are taken down and stored for winter consumption. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

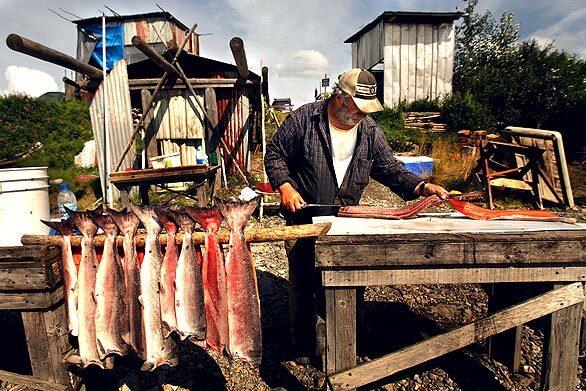

At his cutting table on the banks of the Yukon River, Pat Moore prepares king salmon to be sliced into narrow strips and hung in the smokehouse. It frustrates him when salmon show signs of “white spot disease,” or Ich, which turns their flesh mealy and gives off an unpleasant odor. See, its all of the biggest, best-looking fish, Moore says. It breaks my heart. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

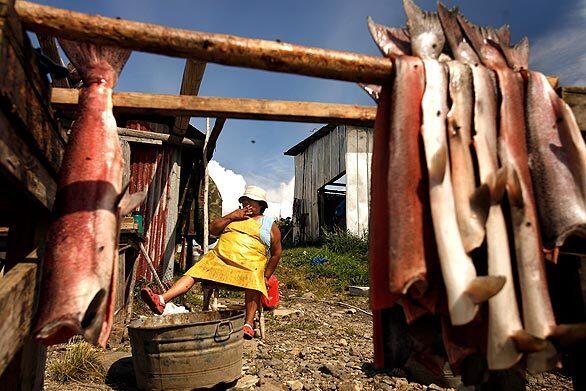

Lorene Moore, a native of Tanana, Alaska, takes a break from filleting salmon caught by her husband, Pat, at their fish camp along the Yukon River. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Piles of diseased salmon are headed for the dogs at Pat Moore’s fish camp. As much as a third of the catch gets tossed when fishermen discover Ich, which is linked to an increase in the temperature of the Yukon River. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

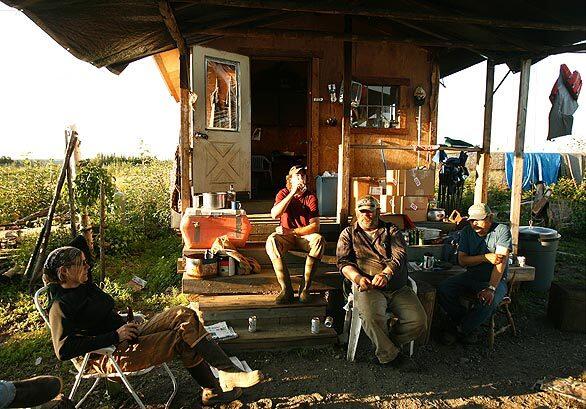

Lara Dehn, a biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, discusses the salmon disease with Pat Moore and his helper, Steve Langenhorst, at Moores makeshift camp. Fishermen have urged state officials to take a more active role in investigating the disease and looking for a solution. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

The sun dips toward the horizon behind Pat Moore’s fish camp on the Yukon River. During the summer months, the sky never gets completely dark. During the winter, Moore and his wife abandon the fish camp for their home in downtown Tanana, about a mile away. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)