‘OK. Let’s do it!’ An oral history of how NASA’s Cassini mission to Saturn came to be

- Share via

In the predawn hours Friday, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft will make a suicide dive into Saturn’s atmosphere, vaporizing like a tiny meteor in the vast Saturnian sky.

It will be a fiery end for a spacecraft built and flown by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory that has spent the last 13 years exploring the ringed planet and its many moons.

Cassini set off for Saturn on Oct. 15, 1997, and spent seven years looping around the solar system before it finally reached its destination. Since then, the two-story spacecraft has revealed that ocean worlds are more common in our solar system than anyone knew, watched moonlets form in Saturn’s rings and found conditions suitable for life on two of the planet’s moons.

The Cassini mission has been an unequivocal success — but its fate was not always certain.

Originally conceived in the early 1980s, Cassini and its companion Huygens lander contended with debilitating budget cuts, narrowly escaped cancellation more than once, and faced last-minute attempts to ground the spacecraft out of fear that a launch mishap would cause radioactive plutonium to rain down on Earth.

Cassini followed in the footsteps of the Voyager and Galileo missions, becoming the last big spacecraft to explore the outer solar system. This is the story of how it got off the ground, told by the people who were there.

Voyager’s unanswered questions

Linda Spilker, Cassini mission project scientist at JPL: Had we not had Voyager, I don’t think we would have had Cassini. The whole reason we wanted to go back to Saturn was because of what Voyager was not able to do there.

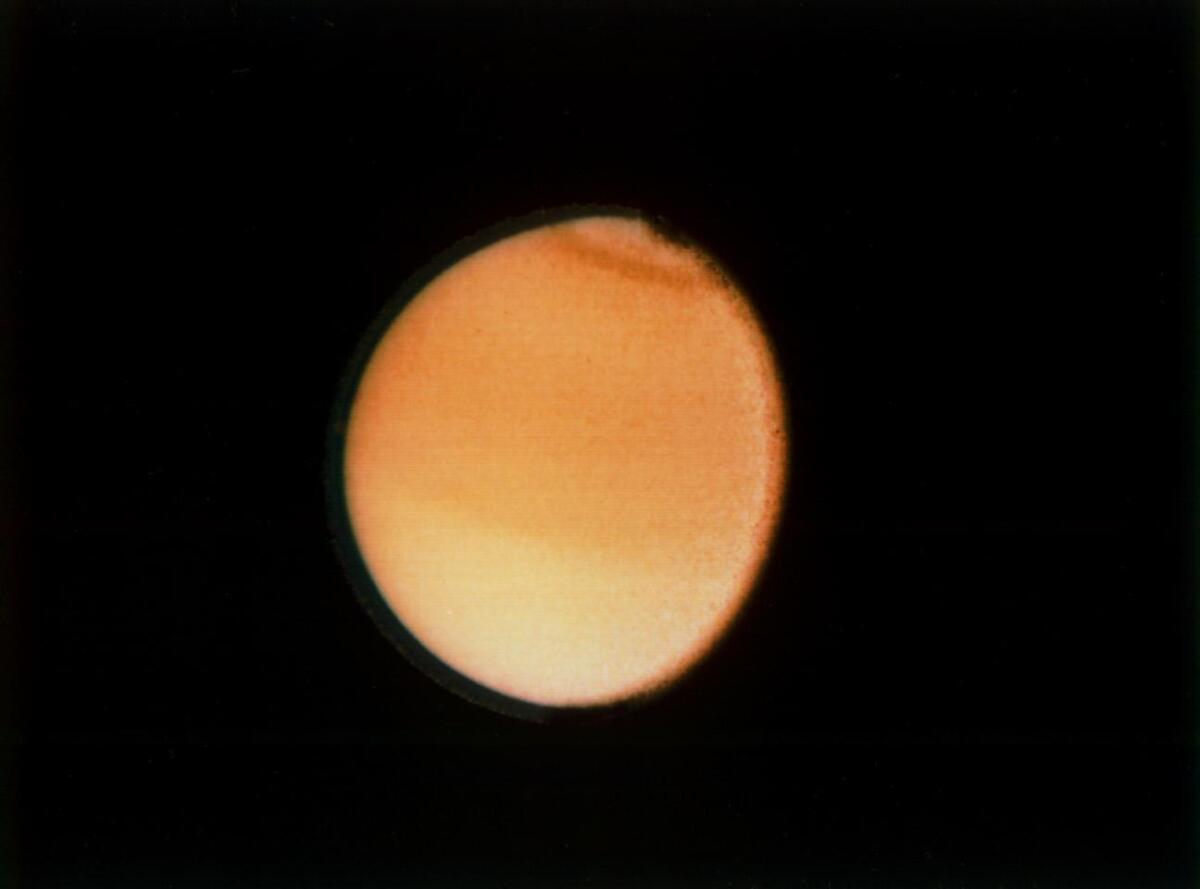

Bonnie Buratti, principal scientist and supervisor of the Comets, Asteroids, and Satellites Group at JPL: Voyager had done a reconnaissance of the Saturnian system and there were all these great discoveries. There was Titan, which looked kind of like an Earth in deep freeze. Enceladus looked like it was covered in snow. And there was Iapetus, a moon with one half as dark as tar and the other half basically as bright as snow. So there were all these mysteries.

Andy Ingersoll, planetary scientist at Caltech: Voyager had also done a lot to reveal the detailed structure of the rings. It was clear that the closer we got and the more time we spent there, it was going to be really fascinating. And it turned out it was.

Hunter Waite, director of planetary mass spectrometry at Southwest Research Institute: It’s like the onion that you peel back. Voyager scratched the surface — it pulled back the first layer.

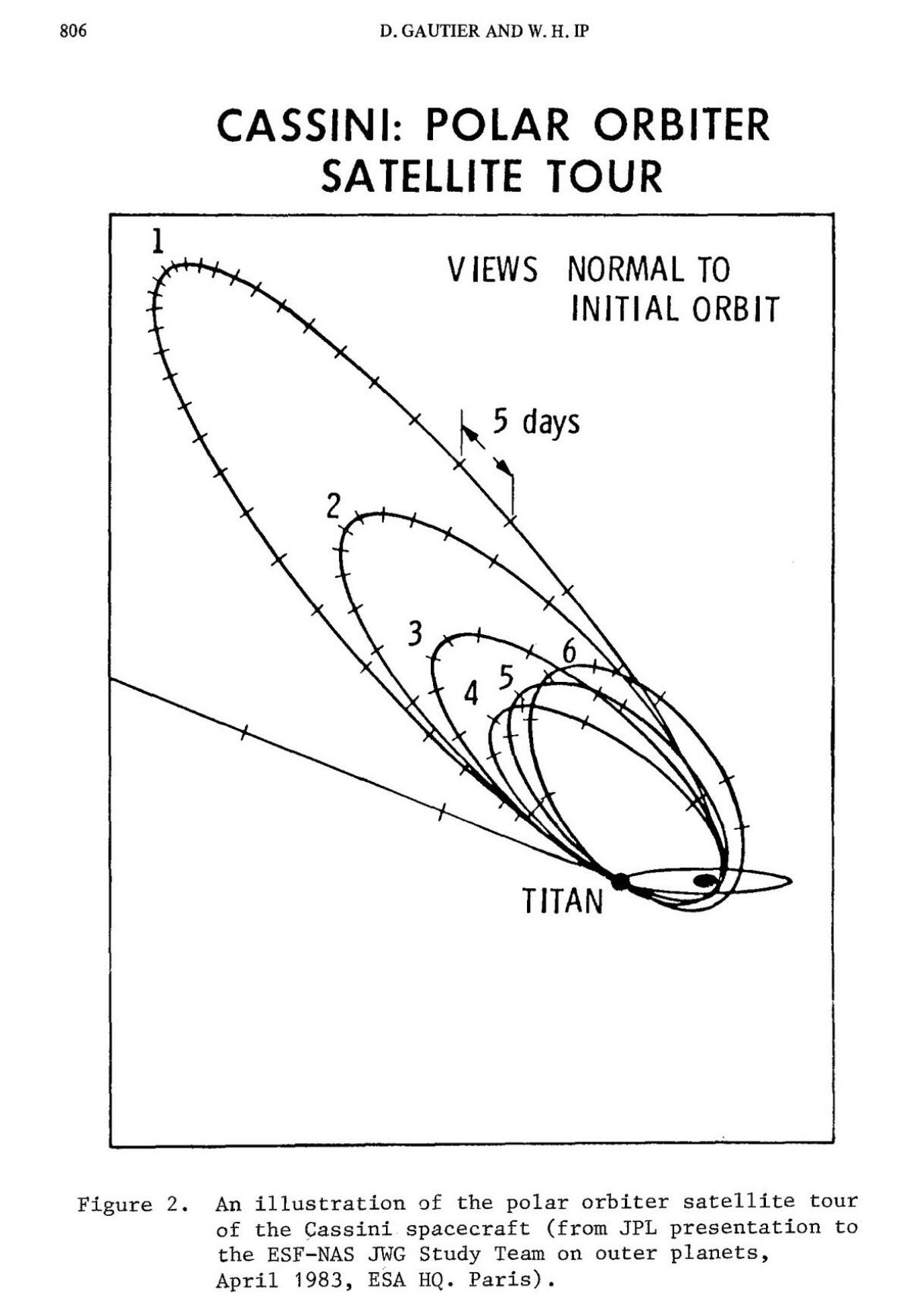

Spilker: With the Voyager 1 flyby in 1980, we flew close to Titan and found that with the cameras and instruments we had, we couldn’t see through the haze to the surface.

Toby Owen, planetary scientist at the University of Hawaii: What lay beneath that smog? Speculation ranged from a global ocean of ethane to a rugged landscape carved out by precipitating hydrocarbons, to a nondescript, gooey surface resembling a refrozen chocolate ice cream dessert.

Daniel Gautier, planetary scientist at the Paris Observatory at Meudon: Voyager revealed that the main component of the Titan atmosphere was molecular nitrogen, with a few percent of methane. Laboratory experiments had shown that an irradiated mixture of nitrogen and methane produces complex organic molecules and compounds, including some that are present in living systems on the Earth.

Ingersoll: Toby Owen gets a lot of credit for pushing the Cassini mission, especially the interest in Titan as an analogue of Earth in its early days. Before we had an oxygen atmosphere, before we had life, we could have had a similar atmosphere to Titan’s.

An idea is born

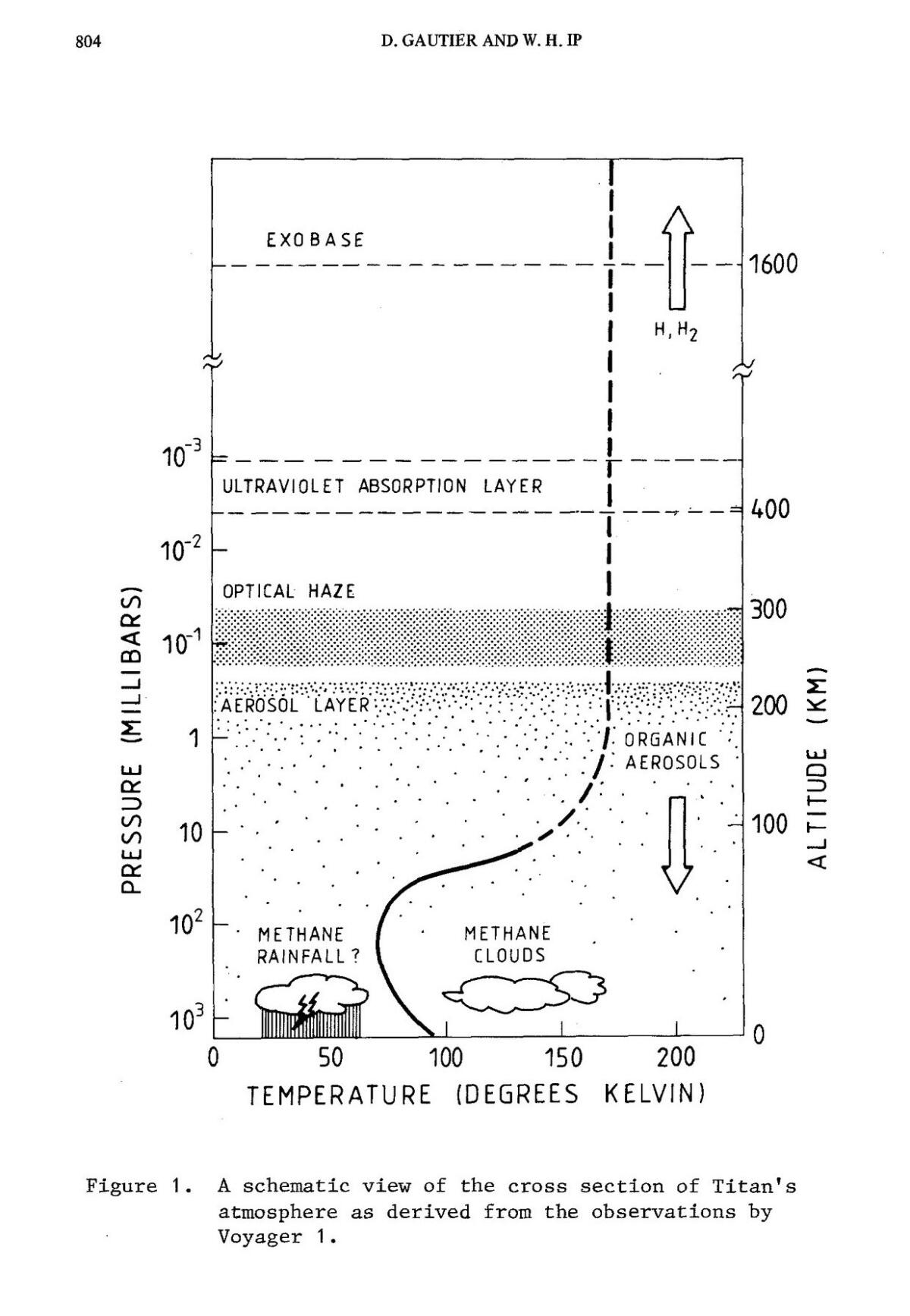

Wing-Huen Ip, planetary scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Aeronomy: The European Space Agency issued a call for mission proposals in July of 1982. Being young and naive, I thought it interesting to propose a Saturn orbiter with a probe to Saturn or Titan.

What Cassini revealed about Saturn's moons »

Gautier: One night after dinner I received a call from a person speaking English with a strange accent. The person was Wing Ip. He explained that he intended to propose an orbiter around Saturn. After some time, I understood that he was proposing to unite our efforts.

Ip: The conversation did not go too well at first. That was partly because Daniel found it hard to believe that someone in Germany might be interested in Titan. And the other part was that we had not understood each other well.

At the critical moment, I said to Daniel, “Dr. Gautier, do you know what this mission is going to be called? It is going to be named ‘Cassini.’” After 10 seconds he said, “OK. Let’s do it!”

Owen: The mission was named Cassini in honor of the first director of the Paris Observatory, Jean Dominique Cassini. In addition to his discoveries in the Saturn system, Cassini also embodies the spirit of international collaboration essential to this mission.

Ip: Naming the mission "Cassini" was quite natural after the Galileo mission to Jupiter. Especially because it would rally the support of France, which is a key member of ESA.

Gautier: Early in November, Wing Ip, Michel Combes of the Meudon Observatory in France and myself wrote the proposal for a Saturn orbiter/Titan probe mission and submitted it to the European Space Agency. It was co-signed by 27 other European scientists. The concept was clearly presented as a cooperative ESA-NASA mission.

Ip: ESA and NASA were not exactly on good terms with each other at that time because of the problem with the Ulysses mission to study the sun (which is another story). Coming on the heels of this controversy, such a close collaboration was not exactly met with enthusiasm.

Meanwhile ...

Owen: In the early 1980s, NASA convened a series of workshops in which designated groups of scientists developed concepts for future missions throughout the solar system. I was the chair of the Outer Planets Group that was determined to include Saturn in the final list of proposed missions.

Although initially we had not been given the right to include collaboration with foreign partners, my long friendship with Daniel Gautier made me well aware of the proposal by Wing Ip and Daniel to develop a European mission to Saturn and Titan with some kind of U.S. partnership.

Ingersoll: I was a member of a National Academy of Sciences planning study committee called COMPLEX. That stood for Committee on Planetary and Lunar Exploration. In 1982 we published a report on the next step in planetary exploration. It was time for an orbiter. The first orbiter was to be Galileo around Jupiter and the second was to be around Saturn.

Epic storms, new moons and worlds that might host life: Here are Cassini's greatest discoveries »

Owen: The first idea had actually been for the Europeans to fly a copy of their highly successful Giotto spacecraft, while the Americans would build copies of the Galileo probe to be launched into the atmospheres of Saturn and Titan. The concept rapidly reversed into a European probe carried by a NASA spacecraft.

Gautier: Technical studies of the orbiter were made by JPL and those of the probe by the European Space Research and Technology Centre.

Owen: The joint ESA-NASA study culminated in a presentation to European scientists at Bruges in 1988. Cassini was in competition with another solar system mission called Vesta that would have explored asteroids, and with three astrophysical proposals as well.

Gautier: Why was Cassini-Huygens the winner of the ESA selection? In part because the mission covers practically all domains of planetology: the physics and origin of the atmospheres of Saturn and Titan, exobiology, internal structure and evolution of Saturn, rings, icy satellites, magnetosphere, asteroids, interplanetary medium.

Owen: Two critical problems remained: to convince NASA that Cassini-Huygens should be its next mission for planetary exploration, and then to convince Congress that they should add the necessary funds to the NASA budget.

Two missions for the price of one-and-a-half

Buratti: NASA is really big on efficiency, so we got the idea of building two essentially clone spacecraft. One would go to Saturn and the other one would go to a comet. Comets are very interesting — they are basically the debris left over from the formation of the solar system.

Ingersoll: They stuck Cassini together with a comet mission called Comet Rendezvous Asteroid Flyby. It became CRAF-Cassini. It was a very kludgy thing, but you have to sell these to NASA higher-ups and ultimately to Congress.

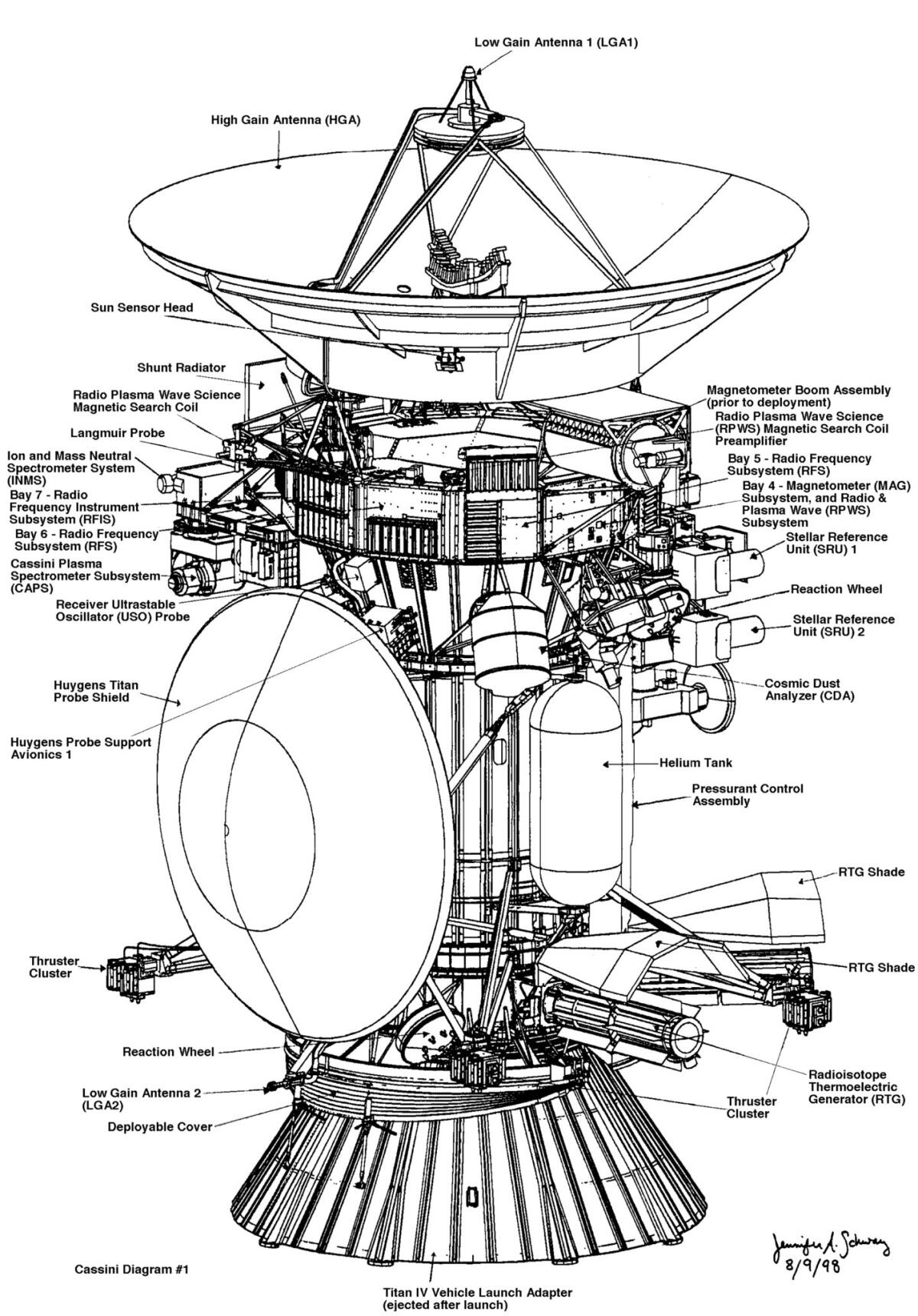

Earl Maize, Cassini program manager at JPL: These large outer-planet spacecraft were very difficult to make, so they tried to make a standard bus called the Mariner Mark II. It was a standard structure of propulsion systems and avionics that one could kit out with whatever instruments you thought were appropriate for the mission.

Owen: I was given the task of presenting CRAF-Cassini to NASA administrator James Fletcher and his advisors. The administrator quickly understood that he was looking at two different missions and asked why we couldn’t simply do Cassini, as he thought it would be more productive and doing just one mission would obviously save money. I made the point that NASA had not launched a planetary mission for 11 years and could certainly afford this beautiful package of two for a bargain price.

Ingersoll: In 1989 I was the division chair of the American Astronomical Society’s Division of Planetary Scientists. I was the first chair to send out email messages to the membership and say, “Write your congressman to support CRAF-Cassini.”

Buratti: It’s not really NASA that makes a decision, it’s Congress. So we had leaders of NASA helping us, we had the director of JPL helping us. We had Ed Stone, who was the project scientist on Voyager, helping us. A whole slew of people did push to originally have both missions.

Owen: Fortunately, enough positive interest was generated by these activities to lead to the inclusion of CRAF-Cassini in the NASA budget. In a reasonable world, that would have been the end of the story.

‘We’ll show we can bleed’

Buratti: There were cost overruns. We couldn’t do both missions, and CRAF was the one that got canceled.

Julie Webster, Cassini chief engineer at JPL: CRAF was canceled in 1992, and if some of NASA headquarters had its way, Cassini would have been canceled at the same time.

Spilker: We wondered if we would be next. There were signs that it was the direction we were headed. It looked likely.

Webster: NASA Administrator Dan Goldin was calling us “Battlestar Galactica.” We were huge in an era when they were trying to go to better, faster, cheaper. He didn’t like having all the eggs in one basket like that.

Waite: People from ESA and France wrote and said how upset they would be at the U.S. if they walked away from this thing. As far I know, that’s what saved it. It was the international outcry.

Spilker: The international collaboration really paid off, but it came at a reduction of cost for Cassini.

Ingersoll: John Casani, who was the project manager at JPL, said, “We’ll show that we can bleed,” and they took away the scan platform.

Buratti: What a scan platform is, it means the instruments are on a moving platform so you can point them rather than pointing the spacecraft. We weren’t able to get that, and that was a big loss.

Ingersoll: Casani said if we want to point the instruments we’ll rotate the entire spacecraft, ponderous as it is. I don’t know how much money it actually saved — 10% or something.

Waite: At the time it was considered absolutely necessary to get Congress to continue the funding. You can’t really dis the people who made the decision.

Webster: The silver lining was the incredible stability of the images taken over hours, because we are very, very stable. It’s like the difference between taking a picture on a tripod and taking a picture with Parkinson's. I think it was a net positive gain for Cassini.

Spilker: The instruments also had to de-scope. Each one had to make cuts to detectors and different capabilities along the way to fit with the new budget we had from NASA.

Maize: We were essentially going to go into this thing with all guns blazing all the time — a 24-hour-science machine. The Cassini we have now is not like that.

The trading board

Spilker: One thing we did that I thought was very smart is we set up a trading board and allowed the instruments to trade for mass, power, data rate and money.

Maize: In all missions there is a fixed amount of power, a fixed amount of mass, and a fixed amount of data bandwidth. So the instruments were allowed to trade various components. For example, I need 2 watts, but I don’t need 2 kilograms — does anyone have an extra 2 watts for 2 kilograms? I’m making it much simpler than it was, but that’s the general idea.

Waite: It was trying to give people an opportunity to not have to meet set guidelines with every instrument but to be able to mix and match. If someone had extra mass they could get more money and so forth. All that mattered to the spacecraft was how much the overall payload was.

Maize: It was an open commodities market on the various very critical resources. Cassini may have been the first to do something like that, but other missions have since used it.

Back on the chopping block

Maize: We were almost canceled again in fiscal year 1995. We had gone through this whole restructuring, we were actually soldering boards and creating real hardware when another big budget crunch came along. We were very seriously on the chopping block.

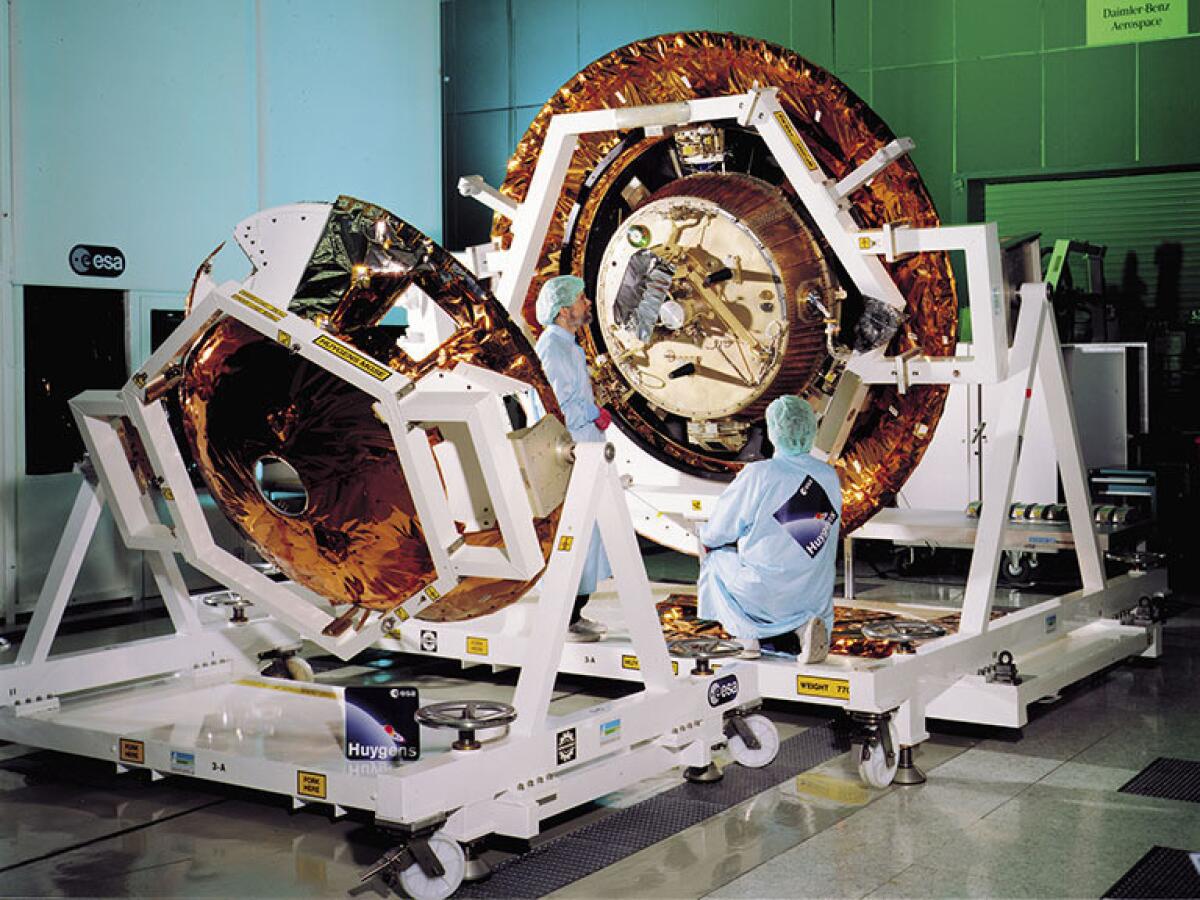

Webster: The Europeans had already built the probe that was going to be launched on the spacecraft, so they wrote letters to Congress and NASA saying, “Hey, we put all this time and effort into this.” They really went to bat for us.

Maize: The European Space Agency mounted quite an intensive campaign to pressure the Clinton administration to reconsider. Because without Cassini, Huygens didn’t have a ride. Fortunately they prevailed. I think without their intervention, Cassini might have met an entirely different fate. Those were very tight times.

Webster: We just kept going on building Cassini. We were still headed to an October 1997 launch. Most of us had been through many cancellation talks on several spacecraft, so we just kept our heads down and kept working.

The plutonium scare

Maize: Saturn has about 1/100th the sunlight as we have on Earth. Solar panels would work, but they would be so inefficient that it would just be ridiculous. In the outer solar system, plutonium is the best power source.

Waite: There were a lot of people protesting because we had plutonium as a fuel. They were trying to lobby against us being able to launch because we were going to kill people and so forth.

Webster: The theory was that we were going to release radioactive materials into the atmosphere if there was a launch failure. You can make bombs out of plutonium 235, but that’s a different isotope from what we used. We used plutonium 238 and we made into an oxide so it’s not a bomb. It’s not fissionable material. But it is radioactive, so it’s hot. We take the heat and put it into a thermocouple and make it into electrical energy. It’s exactly like a solar panel. It just happens to be a radioactive solar panel.

Waite: Plutonium is dangerous stuff but the way it is processed and used in space is pretty darn safe for the most part.

Buratti: Cassini scientists were very confident that the plutonium was packaged in a way that it would not escape the spacecraft in the case of a launch vehicle failure. The conservative engineers at JPL did a number of studies showing this. Many of the Cassini scientists were active in the antiwar and nuclear disarmament movement, so we didn't take these concerns lightly.

Nevertheless there were a lot of protests and a movement to stop the launch. JPL had a whole office to address the public's concerns at that time. I do remember the protesters: They were few but vociferous. They were mainly at Cape Canaveral, but I seem to remember a few stragglers at JPL as well.

Maize: I tend to be pretty green on environmental issues, but I had seen so many precautions taken and the reliability of these systems was so high. I don’t want to dismiss the concerns of the folks who were worried about it, but I really felt we had this more than covered.

Webster: Our project manager at the time, Richard Spehalski, was on “60 Minutes” right before we launched. He basically looked at the “60 Minutes” guys and said, “My grandchildren are watching the launch. If I was worried about this, would I have my grandchildren watching the launch?”

Epilogue

There would be more nail-biting moments to come over the 20 years Cassini spent in space: a harrowing 90-minute engine burn to enter Saturn’s orbit, Huygens’ 2.5-hour descent to Titan — “I’m still trembling with fear from that time,” said Ip — and, just a few weeks ago, the spacecraft’s first dip into Saturn’s atmosphere. Cassini sailed through these hurdles, and many more.

“We’ve been so lucky that so little has gone wrong,“ Spilker said. “Like Earl Maize has said, the toast falls butter-side up with Cassini.”

The original four-year mission was extended twice. And even now, it’s ending only because the orbiter has run out of fuel. Nearly all its instruments are still functioning properly.

“Cassini was always the best athlete, the best child in school,” Webster said. “More than a thousand people worked on the spacecraft in some capacity. And look what they accomplished.”

About this story

These interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Linda Spilker, Bonnie Buratti, Earl Maize, Andy Ingersoll, Hunter Waite and Julie Webster were interviewed in person.

Toby Owen, Daniel Gautier and Wing-Huen Ip's comments were taken from first-person reminiscences published in the Proceedings of the International Conference “Titan — From Discovery to Encounter.”

Ip worked at the Max Planck Institute for Aeronomy at the time of the events in the story. He is now a planetary scientist at the National Central University in Taiwan.

Do you love science? I do! Follow me @DeborahNetburn and "like" Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE ON THE CASSINI MISSION

After 13 years at Saturn, NASA’s Cassini spacecraft is ready for its grand finale

Check out Cassini’s jaw-dropping discoveries of Saturn’s moons

Epic storms, new moons and worlds that might host life: Here are Cassini's greatest discoveries

Here's the nothingness Cassini heard as it flew through the empty space between Saturn and its rings