Key instrument on NASA’s InSight lander is stuck. A Martian rock may be to blame

- Share via

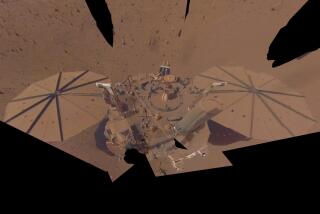

NASA’s Mars InSight mission has hit a snag: Its heat probe appears to have struck an obstacle just below the surface of the red planet.

The instrument, which was designed to hammer itself 16 feet underground, encountered some kind of resistance over the weekend and hasn’t made progress since.

For the record:

6:45 p.m. March 5, 2019An earlier version of this story said the heat probe’s digging ability was tested at JPL. Those tests occurred in Germany, where the instrument was developed.

On Tuesday, scientists announced they would stop hammering and try to find a way around the problem.

The team operating the probe is attempting to dig the deepest hole ever drilled on another planet with a tool that weighs less than seven pounds and uses less power than a cellphone. It’s not exactly easy.

“We knew from the beginning that this part of InSight was a risky part,” said Tilman Spohn, the principal investigator in charge of the heat probe.

The team members also knew they might be stymied at some point. “But we were a bit surprised that it came so soon,” said Spohn, a researcher with the German Aerospace Center in Berlin.

The Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package, or HP3, was successfully deployed by the lander’s mechanical arm on Feb. 12. Its mission is to measure the heat escaping from Mars’ interior, which will give scientists clues about the planet’s composition and history.

Engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge first tried to fire up the probe — nicknamed “the mole” — last week. But the command failed to reach the Mars Odyssey orbiter, which was supposed to pass it on to InSight in a game of interplanetary telephone.

After two days of delay, the burrowing got underway on Thursday. The mole punched out of its housing and into the Martian soil, making quick progress during the first five minutes.

Then something changed. The mole continued hammering for four more hours, but it couldn’t go much deeper. In addition, it is now pitched to one side, leaning about 15 degrees off vertical.

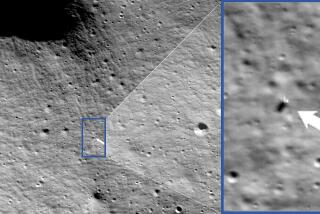

Mission scientists estimate the probe has reached a depth of about a foot, meaning one end of the 16-inch mole is still sticking out of the ground.

“We are a bit worried,” Spohn wrote in the mission logbook, “but tend to be optimistic.”

Why is Mars so different from Earth? NASA’s InSight mission will dig deep to find answers »

The most likely explanation for the holdup is that the probe has hit a buried boulder or a layer of gravel.

Scientists picked InSight’s landing spot because it appeared to be soft and sandy. However, they were aware that something like this was a possibility.

“We can’t truly see into the subsurface,” Sue Smrekar of JPL, the deputy principal investigator for the heat probe and the overall mission, said in November before InSight landed. “We can always hit a rogue rock.”

Tests conducted in Germany, where the instrument was developed, suggest the probe should be able to work its way around small rocks and through layers of pebbles. Based on its tilt, researchers surmised it may have already fought its way past one obstacle, only to immediately encounter another.

Engineers tried a second bout of hammering on Saturday to see whether the probe could push through.

“Keep your fingers crossed!” Spohn wrote in the logbook before the attempt.

But from what researchers can tell, the effort yielded little success.

“We cannot really say that we did no progress on Saturday, but we can say that we did not make enough progress,” Spohn said.

Now the researchers have decided to pause the project for two weeks to come up with a new plan and test it using models and spare instruments housed at JPL.

Smrekar said team members are waiting to receive images and other data from the lander that will help them “better assess the situation.”

The good news, Spohn said, is that “we are still in a situation where we could do something about it.” Since part of the mole is above ground, researchers are considering whether to use the robotic arm to press on the probe and absorb some of the shock from hitting the obstacle. They could also use the arm to try to right the instrument. Or they could also decide to keep hammering, since tests of the probe showed that it often takes time for the mole to work its way around obstacles.

“I’m reasonably optimistic that we can figure out ways of handling it, and at least convince it to go a little deeper,” Spohn said.

The probe itself still seems to work fine, and researchers will take advantage of the break to collect the first round of data.

The mole will measure how quickly a pulse of heat spreads through the Martian soil, giving scientists a better sense of the surface material. “If worse came to worst,” Spohn said, “then we would at least be able to do that.”

Another instrument in the HP3 package has already started to track changes in the surface temperature during eclipses of the moon Phobos, which orbits Mars every eight hours. This week, it will cast a shadow over InSight’s landing site three times.

The first eclipse occurred Tuesday, and Spohn said preliminary data registered a slight cooling. The speed and degree of change tell researchers about the nature of the Martian surface, he said.

These readings will help scientists gauge the planet’s heat flow more accurately if and when the mole is finally deployed as planned.

InSight’s team members still hope that will happen, but they know better than to take anything for granted.

“Planetary exploration is not as easy as pie!” Spohn wrote Tuesday in the logbook.