Federal panel recommends general physicians screen all adults for depression

A federal task force recommends that physicians screen pregnant and postpartum women for depression -- as well as all other adults.

- Share via

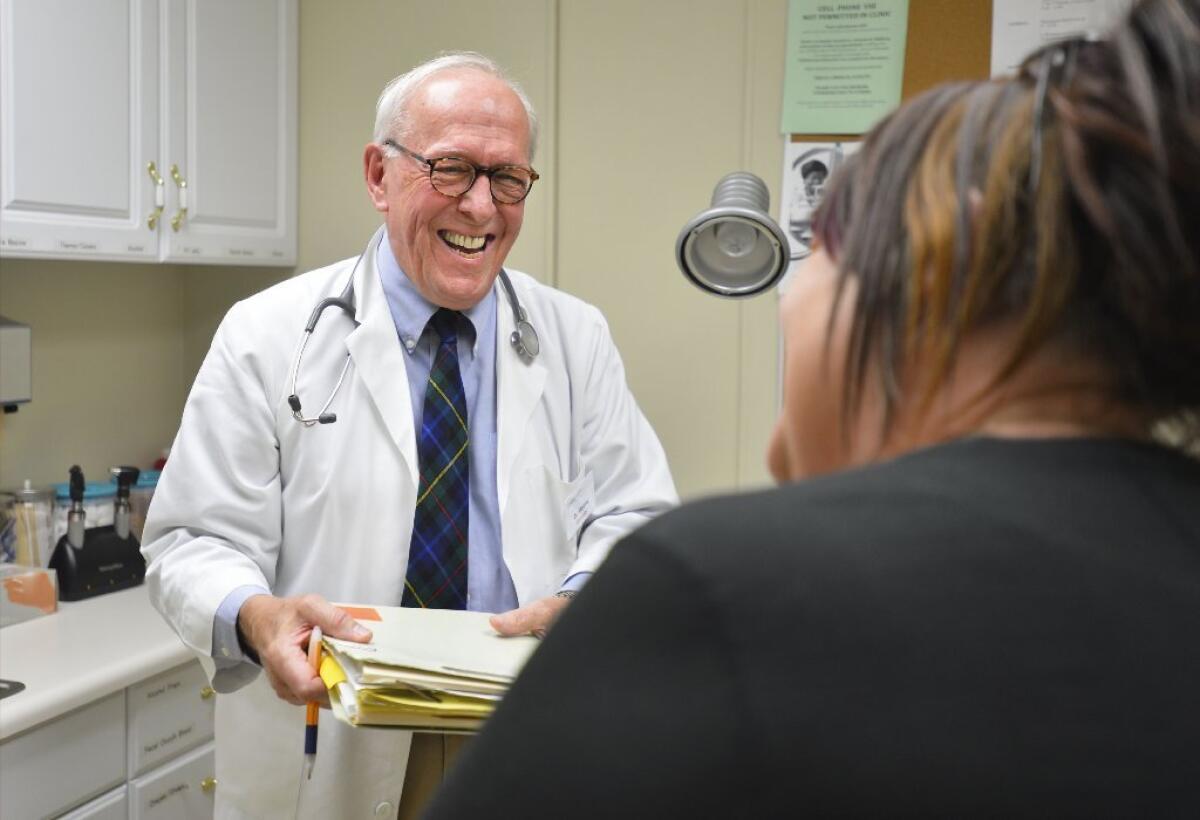

In a sign that the treatment of depression is shifting to the mainstream of American medical care, a federal panel has recommended that general physicians screen all adults for depression and treat those affected by the mood disorder with antidepressant medication, refer them to psychotherapy or do both.

For the first time, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force also advised that physicians assess all pregnant and postpartum women for signs of depression, as well as elderly adults.

The task force, which assesses the harms and benefits of screening programs and makes recommendations accordingly, said that screening pregnant and postpartum women for depression would have a “moderate net benefit.”

See the most-read stories in Science this hour >>

At the same time, the panel acknowledged that, given the small risk that treatment with antidepressants could harm a developing fetus, pregnant women with depression should be offered a “range of treatment options,” including cognitive behavioral therapy, which has been found effective in relieving depressive symptoms.

The new recommendations, published Tuesday in the Journal of the American Medical Assn., ensure that virtually all adults consulting with a physician will at some point be asked a battery of questions aimed at discerning the signs of depression. Among those are prolonged sadness or irritability, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, disturbances of sleep or appetite, and loss of energy and interest in activities once a source of enjoyment.

The federal panel’s advisory issued Tuesday departs from an earlier slate of recommendations on depression screening by urging that physicians look for signs of depression, at least periodically, in all of their adult patients.

The last time the task force took up the subject in 2009, it recommended physicians screen adults for depression “when staff-assisted depression care supports are in place.” Physicians without staff to make referrals or to counsel patients on how to seek further treatment were left to decide for themselves whether they should screen their patients for depression.

Now, the panel said, “such support is ... much more widely available and accepted as part of mental health care.” Physicians who provide general care for adults should have “systems ... in place to ensure proper diagnosis, treatment and follow-up care for depression,” the task force added.

“What this recommendation is saying is that, as a country, we don’t have an excuse” for failing to diagnose and treat depression, said UCLA psychiatrist Dr. Nelson Freimer, director of a university-wide initiative that aims to improve depression care and uncover the biological bases for the disorder.

“This is one of the nation’s leading killers and causes of disability, and it has enormous effects throughout our society. It’s just too important to be optional,” Freimer said.

He added that the task force’s recommendation that pregnant and postpartum women be screened underscores the powerful impact that a mother’s depression has not only on her own well-being but on that of her child.

“If I’m depressed right after giving birth and have a newborn depending on me, it has an enormous effect,” said Freimer. “It’s important we don’t miss any cases.”

In the United States, as many as 1 in 5 women who give birth each year is thought to have postpartum depression symptoms.

In 2009-12, the most recent period for which statistics are available, 7.6% of Americans over the age of 12 were thought to suffer from moderate to severe depression. A recent study estimated the yearly economic burden of the disease--in lost wages, cost of treatment and suicide-related costs--to be $210.5 billion in the United States.

As more seek care for depression, those numbers will probably increase. Experts say that depression, which is more common in women and among low-income Americans, remains significantly underdiagnosed. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that only about about a third of those experiencing severe depressive symptoms have had contact with a mental health professional in the previous year.

Increasingly, physicians in family medicine and general care are the first to suspect depression in their patients. Those doctors’ growing role in prescribing antidepressant medication has driven the growth of those drugs, which, despite doubts about their effectiveness, are the third most commonly prescribed class of medication in the United States.

In 2010, more than 253.6 million prescriptions were filled for antidepressants, according to a report by IMS Health.

Roughly half of patients who seek treatment for depression, however, do not report their symptoms having resolved completely, said Freimer.

Over the next 10 to 15 years, UCLA’s Depression Grand Challenge is expected to screen all patients cared for by the university’s healthcare system--more than a million patients. Under the initiative, the university expects to enroll 100,000 participants into research studies that will explore the genetic and neural bases of the disease and seek better ways to match depression sufferers to treatments that are effective.

An editorial on the task force’s recommendations, also published in JAMA, said that although progress in recognizing and treating depression has been substantial, “there is still much work to be done.”

Dr. Michael E. Thase, professor of psychiatry at University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, wrote that physicians treating depressed patients will have to be prepared to follow up to determine whether the treatment is working, and change course if it is not. In time, he expressed hope that “better methods to match patients with specific forms of treatment”--one of the aims of the UCLA initiative--will be found.

Follow me on Twitter @LATMelissaHealy and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.

MORE FROM SCIENCE

Bizarre birth defect is on the rise, and researchers are baffled

Overweight children are a growing problem in Africa and Asia

Astronomers’ findings point to a ninth planet, and it’s not Pluto