Few takers for free anti-COVID pills at Bay Area ‘test-to-treat’ site

- Share via

BERKELEY, Calif. — After avoiding movie theaters, restaurants and gyms for more than two years, Helen Ho decided to take her first big risk since the start of the pandemic to attend her graduation.

In late May, Ho, 32, flew to Cambridge, Mass., to collect her PhD in public policy from Harvard University. A few days after returning home to the Bay Area, she tested positive for a coronavirus infection. At first, the Ivy League-educated researcher found herself at a loss for what to do.

“The protocols on how to respond after you test positive are extremely confusing,” Ho said.

But a few days later, after talking to an advice nurse, she found herself in the scrubby courtyard of a defunct senior center in West Berkeley that had been transformed into one of the state’s new “test-to-treat” sites.

The senior center is one of 138 free COVID-19 testing locations that California has expanded into one-stop treatment sites to improve the accessibility of antiviral medication. The state’s initiative is modeled after the Biden administration’s “test-to-treat” program, announced in March, which aims to provide high-risk patients who test positive with instant access to antiviral medications. To do so, California is contracting with OptumServe, a Minnesota-based managed-care company, to spend $18.2 million a year on the effort.

One month into the initiative at sites from Eureka to San Diego, state health workers are slow to get Pfizer’s Paxlovid and Merck’s molnupiravir into the hands of patients, who must take them in the first few days of symptoms to avoid serious illness. Officials say fewer than 800 people statewide have received prescriptions at OptumServe sites despite new COVID infections reaching an average of nearly 14,000 a day in early June in California.

COVID-19 patients now have new treatments they can take at home to stay out of the hospital — if doctors get the pills to them fast enough.

And though the initiative aims to serve the uninsured, about two-thirds of those undergoing screenings already have insurance. For those with health coverage, OptumServe bills the insurer and then reimburses the state.

Dr. Tomás Aragón, the state public health officer, said the goal of the test-to-treat campaign is to “ensure high-risk patients have access to treatments that can keep them out of the hospital.”

The state says its priority is to make the pills accessible to millions of older, chronically ill and disabled Americans, especially the poor and uninsured — even if few people have heard about the drugs.

Liliya Sekreta, head nurse at the West Berkeley OptumServe site, has seen demand for testing and treatment ebb and flow. During the winter’s COVID-19 surges linked to the Omicron and Delta variants, the line for tests extended around the corner of the senior center.

“We had the National Guard here and extra staff on duty to make sure people didn’t get angry or antsy,” Sekreta recalled. At the time, rapid tests were not widely available.

These days, the site is run by a skeleton staff of two young nurses, a couple of medical assistants and a burly Spanish-language translator. Located a few blocks from University Avenue, Berkeley’s main drag, it’s in a formerly working-class neighborhood of stucco bungalows.

On a foggy morning in early June, medical assistants stayed glued to their phones between patients, who trickled in for tests at a rate of one every five minutes.

The White House wants to make Paxlovid pills more accessible as it projects that coronavirus infections will continue to rise during the summer.

Ho was one of them. She is among millions of Californians at risk of getting seriously ill from the virus — in her case, because she takes immunosuppressive drugs for chronic arthritis. Ho has health insurance, but a nurse who answered the advice number at the bottom of the text message notifying her of a positive coronavirus test result suggested it might be easier to return to the OptumServe site in West Berkeley where she’d gotten her test to find out whether she was eligible for antivirals.

Though she felt fine, Ho knew it was important to get treatment early. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says Paxlovid and molnupiravir are nearly 90% effective at reducing hospitalizations and deaths from COVID-19 if taken during the first five days of symptoms.

The FDA authorized the pills in December for emergency use, but supplies were initially scarce. By April, production had increased but, by that time, few physicians seemed to be prescribing the medicine, with pharmacists nationwide reporting stacks of unused antivirals on their shelves.

“I had read the reports about people who should be taking these meds,” Ho said. “But they just didn’t know about them.”

She also worried about infecting her elderly mother, whom she lives with along with her husband and 14-month-old son in the city of Albany.

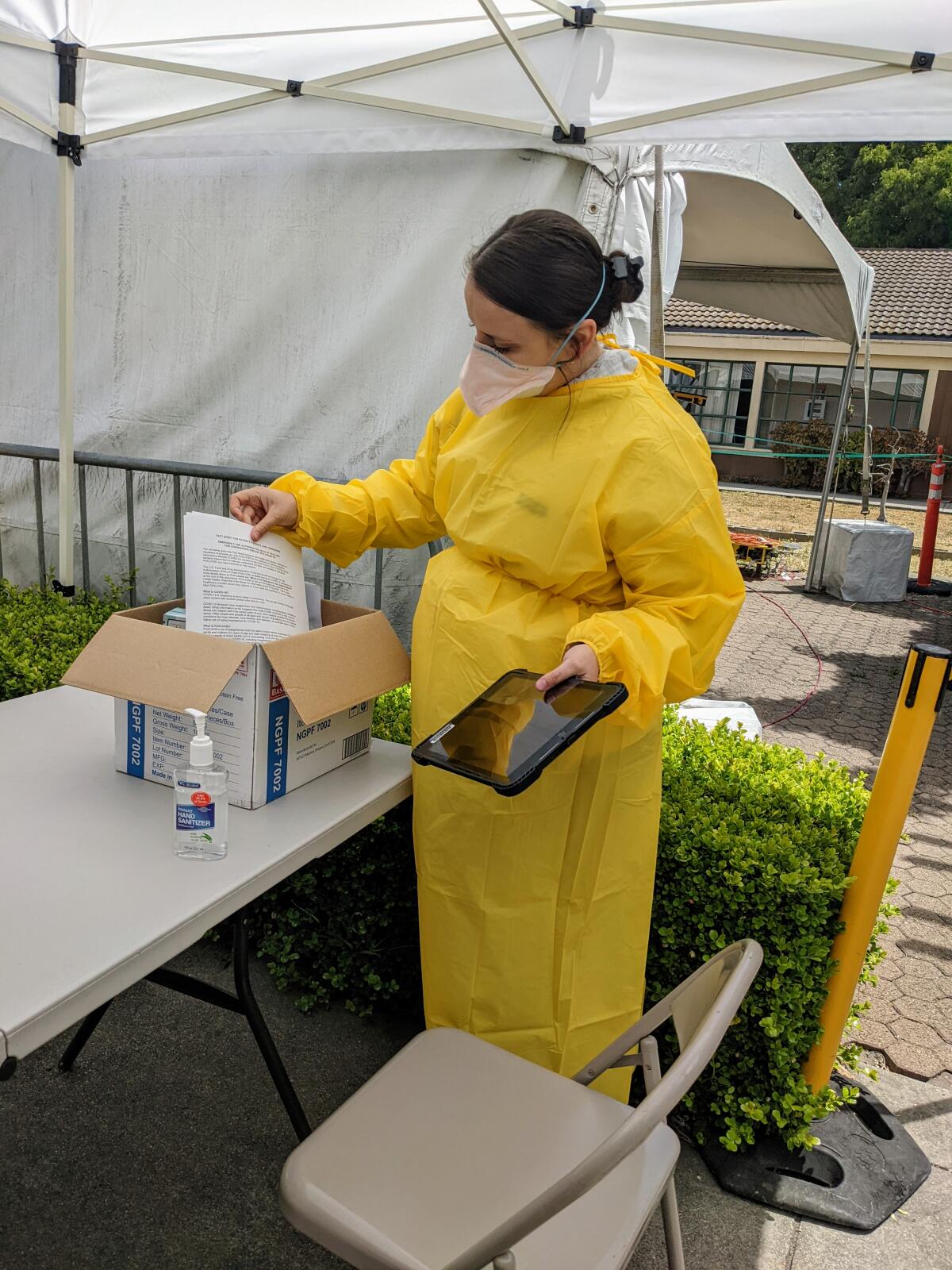

Ho sat at a folding table across from a nurse draped in yellow plastic and answered questions to determine her eligibility for the pills. Afterward, Ho talked via iPad with a doctor who concluded Ho would be eligible for a prescription if she showed symptoms. Those who qualify can go home with the medicines without having to make a trip to the pharmacy.

“I was glad to have somewhere to go that was accessible,” said Ho. “But honestly, it wasn’t very well advertised. Not everyone has the time to call around like I did and ask, ‘What should I do next?’”

There is no longer a shortage of anti-COVID medications in most locations, California health officials say.

Screenings for treatment can take up to an hour and a half. Workers must make sure the patient isn’t taking a drug that can interact with the antivirals, including cholesterol-lowering medications and some birth control pills. Sekreta, the head nurse, said patients who may qualify include those 65 and older, people with chronic diseases, and those who are obese or unvaccinated. People shouldn’t take the pills if they are too sick, or if they’re not sick at all.

Such in-person screenings have made the test-to-treat model confusing and inefficient, said Dr. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, an epidemiologist at UC San Francisco.

“It should be easy — if the doctor says yes — to get these pills by telehealth,” she said.

So far, staffers say, demand for medicine has been low enough that no one in need has had to wait long. Officials said 1,219 people statewide had been screened for the drugs at OptumServe sites as of mid-June, and 768 of them walked away with Paxlovid pills.

“I think it’s a new concept that people are still getting used to,” said Katharine Sullivan, a Berkeley city employee overseeing the West Berkeley site, which has served as a community testing site since early in the pandemic.

Some residents prefer the peace of mind of speaking to a nurse or doctor over taking a test at home.

When Mary White, an art teacher and Berkeley resident of 53 years, came down with cold symptoms in late May, she got on her collapsible bike and rode to the West Berkeley center for a coronavirus test, where she’s gone for tests since the first months of the shutdown. White has health insurance but said she finds this more convenient than the hassle of trying to schedule an appointment that might be days away at a Kaiser Permanente facility in neighboring Oakland.

For the first time, her test came back positive.

“I was just like, ‘Oh, no! What can I do? I’ve got to do something!’” said White, 74.

She returned to the center and underwent antiviral screening. After meeting remotely with a doctor in Chicago, she left with a full five-day course of Paxlovid, which she took for just two days before stopping because the drugs made her feel nauseated.

Back for a follow-up test a few days later, White reported feeling much better following the age-old remedy of rest and fluids. She added that with no end to the pandemic in sight, she was grateful for a community facility where locals could simply walk in and talk to a health worker.

“For people like me,” she said, “that’s very comforting.”

This article was produced by Kaiser Health News, one of the three major operating programs at the Kaiser Family Foundation.