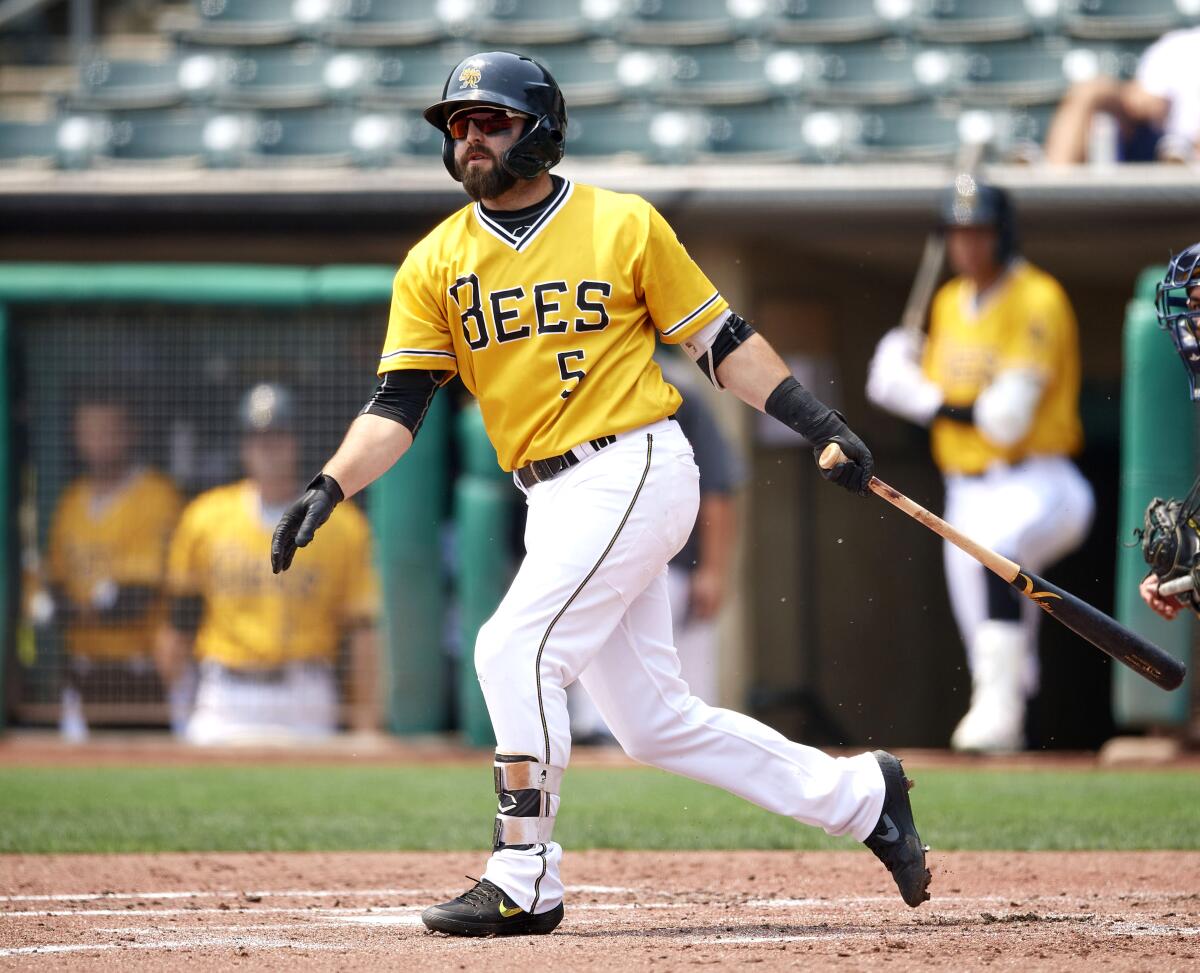

Consistent contact propels unheralded Michael Stefanic to the cusp of Angels roster

- Share via

SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. — A bonus baby, Michael Stefanic is not. When the former Westmont College infielder signed with the Angels as a nondrafted free agent in July 2018, he did not receive one penny. All he got was a bus ticket to Phoenix and the promise of a few rookie-league at-bats in the Arizona Summer League.

“I was just so grateful for the opportunity, I didn’t care,” Stefanic said after a workout at minor league camp this week. “I was one of those guys who said, ‘Shoot, I’ll play for free.’ So when I got my first $250 check after the first two weeks, I wasn’t disappointed. I was like, ‘I’ll get some meal money out of this.’ ”

The paychecks are still light, but Stefanic’s circumstances have changed dramatically since that no-budget signing, three seasons of feasting on opposing pitching and a selection to the triple-A all-star game last summer moving him to the cusp of the big leagues.

Stefanic, 26, shot through the Angels’ farm system like a line drive to the gap, jumping from rookie ball in 2018 to Class-A in 2019 and, after the coronavirus wiped out the 2020 minor league season, to double-A and triple-A in 2021.

He raked at every stop, building a resume that includes a .314 average and .824 on-base-plus-slugging percentage in 241 minor league games with just 129 strikeouts in 1,019 plate appearances.

He added 20 pounds of muscle during the 2020 shutdown, infusing his offense with much-need power, and his home run totals jumped from three in 2019 to 17 in 2021. He hit .334 with a .913 OPS, 16 homers and 54 RBIs in 104 games for triple-A Salt Lake last season.

Major League Baseball said the season would not start until at least April 14. An international draft is a big issue holding up a new collective bargaining agreement.

A second baseman with limited range, quickness and arm strength, Stefanic spent the last five months in Arizona shoring up his weaknesses and expanding his defensive versatility to prepare for a utility role. He was one of 14 non-roster players who were invited to big-league camp on Friday.

“It’s a testament to his character and perseverance as a player, for sure,” said Robert Ruiz, Stefanic’s coach at Westmont, an NAIA school in Santa Barbara. “He was relentless in his pursuit of finding an opportunity to play at the next level. And he didn’t take the first five no’s as his final answer.”

Stefanic, who grew up in Boise, Idaho, has always been overlooked, and not just because of his smallish 5-foot-10, 180-pound frame. He did not receive any major college offers out of high school and wound up at Westmont after catching the eye of Ruiz at a summer camp at Stanford.

“When he got here, you kind of question some of his tools, try to figure out where he’s going to fit in,” Ruiz said. “He’s scrappy, maybe a role player, and you think by his junior year, maybe he’ll have a chance to help you out. He had an unreal fall as a freshman, found his way into the starting lineup and never came out.”

A four-time All-Golden State Athletic Conference selection from 2015-2018, Stefanic hit .363 with a .901 OPS, 275 hits, eight homers, 50 doubles and 124 RBIs in 198 college games, but even more impressive, he struck out only 33 times in 853 plate appearances.

“Yeah, unreal,” Ruiz said. “It was a good approach, elite-level pitch recognition, knowing the strike zone. He’s that guy, if the umpire calls strike three and he takes the pitch, you kind of feel like the umpire was probably wrong.”

“Somebody went down in the AZL and they needed a body. I guess I was that body.”

— Angels prospect Michael Stefanic

Professional scouts, however, saw deficiencies in Stefanic: A lack of speed, arm strength, power and defensive versatility. Forty rounds of the 2018 draft passed, and Stefanic was not among the 1,214 players selected.

“It was devastating, kind of soul-crushing, honestly,” Stefanic said. “I was in a bad place mentally because I had such a good college career and was so confident that I could perform at the pro level.”

His then-girlfriend had an uncle in the San Diego Padres front office who suggested Stefanic put together a resume and highlight video and send it to all 30 clubs. Stefanic e-mailed it to 150-200 executives, most of whom didn’t respond.

“It was kind of a shot in the dark,” Stefanic said, “hoping someone would take a chance on me.”

A month later, Stefanic returned home from an interview for a legal assistant job with a law firm in Santa Barbara when he got a call from then-Angels player development coordinator Chris Mosch.

“Somebody went down in the AZL and they needed a body,” Stefanic said. “I guess I was that body.”

The lockout is preventing the Angels from many important matters, including checking on the status of injured players Mike Trout and Anthony Rendon.

Stefanic entered his first game as a pinch-runner, singled in his first at-bat, “and after that, it was like, ‘Game on, let’s do it, I can handle this,’ ” Stefanic said. “And that’s how I continued to approach things.

“I don’t care who’s on the mound, or what they’re throwing, they have to throw the ball over the plate, I have to put the bat on the ball, and let’s see who wins.”

One of baseball’s oldest adages is that if you can hit, they’ll find a spot for you. The Angels did last season for Jose Rojas, who, much like Stefanic, was a lowly regarded prospect from an NAIA school (Vanguard University) who put up great minor league numbers before reaching the big leagues last season.

“He’s been a huge inspiration to me,” Stefanic said of Rojas, a college opponent for two seasons. “He showed that it’s possible, and I hope to be the next one.”

If Stefanic is, it will be because of a natural feel to hit with a swing that hasn’t changed since he was 12 years old and an old-school two-strike approach that will warm the hearts of purists who long for a game with fewer whiffs.

“I heard this the other day, and I really liked it: The first two strikes of the at-bat are yours, and when you get to two strikes, the at-bat is for the team,” Stefanic said. “So when I get to two strikes, I’m really just looking to hit a low line drive and put the ball in play, no matter where it is.

“Putting pressure on the defense is good, in my opinion. That may be counterintuitive to the way the game is played now, but I’m never gonna be a 50-homer guy. That’s just not who I am. But you know who is? Shohei Ohtani and Mike Trout. I just have to get on base for those guys, and they can hit me in.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.