MLB’s extra-inning rule is a hit with some, a whiff with others

- Share via

May 1 was the 101st anniversary of a remarkable if obscure baseball game rediscovered every year. On that date in 1920, Leon Cadore, a right-hander for the Brooklyn Robins, and Joe Oeschger of the Boston Braves tossed 26-inning complete games opposite each other. Cadore is estimated to have thrown 338 pitches. Oeschger tossed 316. The game ended in a 1-1 tie because of darkness after 3 hours and 50 minutes.

The Dodgers — the Robins’ descendants — were in Milwaukee for the anniversary this year. Cadore’s name accordingly resurfaced during the television broadcast while the Dodgers and Brewers played a game that would’ve been unrecognizable to him.

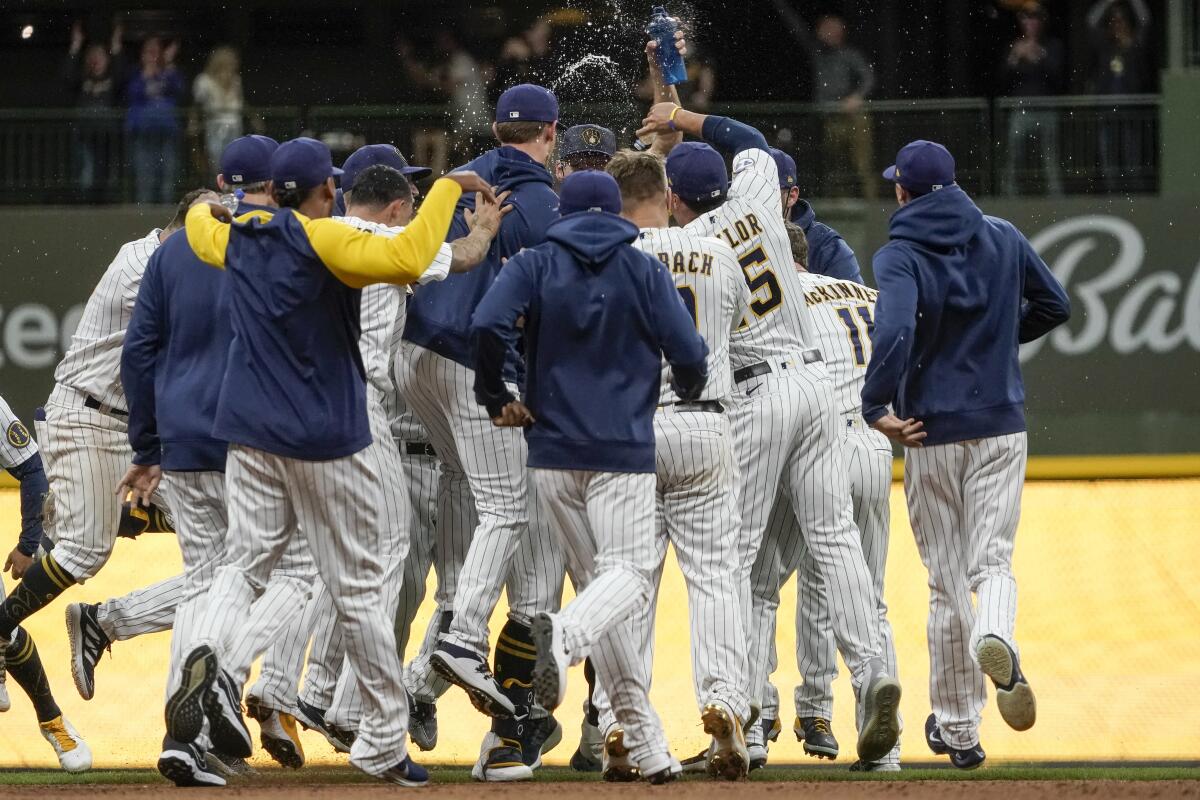

The Brewers beat the Dodgers that day, 6-5, in 11 innings at American Family Field. Starter Dustin May blew out his elbow in the second inning and the Dodgers used 10 pitchers. The Brewers countered with six. The Dodgers, left without a bench, used Clayton Kershaw as a pinch-hitter with the bases loaded in the 10th inning for the second time in a week. The game still lasted 4:48.

It probably would’ve gone longer if a runner wasn’t placed at second base to start each extra inning. It’s a rule Major League Baseball — an institution slow to enforce change in recent decades — initially implemented in 2020 to expedite results during the pandemic-shortened 60-game regular season after trials in the minors. It was kept for the 2021 regular season — not the postseason — after widespread approval outweighed initial aversion. The rationale: The league wants to avoid marathon games for both baseball and entertainment purposes.

Starting pitcher Dustin May left in the second inning with an arm injury, and the Dodgers lost 6-5 to the host Milwaukee Brewers in 11 innings Saturday.

On the baseball front, shorter games help reduce injuries when pitchers are throwing harder than ever while limiting the need for teams to hastily overhaul bullpens for fresh arms. As for entertainment, MLB has been spurred by the reality that most fans aren’t sticking around to watch regular-season games go 15 innings at the pace games are played today.

“The current regular season extra innings rule has been enormously popular with our fans and with our Clubs, and has significantly reduced the length of extra-inning games,“ Morgan Sword, MLB‘s executive vice president of baseball operations, said in a statement.

The rule isn’t a permanent solution — at least not yet. The league and players’ union are expected to discuss permanently adopting it when the current collective bargaining agreement expires Dec. 1.

The league considered several ideas before choosing “the minor league rule,” including ending games in a push to make the next day’s game worth two wins, having a statistic serve as the tiebreaker after the ninth inning (most hits or fewest strikeouts are examples), taking one fielder off the field each inning, a home run derby, and sudden death to end the game after an extra half inning.

In the sudden-death scenario, a situation would be created in which the team on offense has a roughly 50% chance of scoring (a runner at first with nobody out or runners at first and second with one out are possible examples). If the team on offense scores, it wins. If not, the team on defense wins.

The league also contemplated enforcing the answer adopted by sports leagues around the world: the tie. Though an odd concept — even sacrilegious to some — for Major League Baseball, Japan’s Nippon Professional Baseball league and Korea’s KBO League, the highest level of baseball in those countries, have ties after 12 innings.

What happens if a player tests positive for COVID-19? Will there be a universal DH? How large are the rosters? Will there be exhibition games? Here are answers.

Miami Marlins third base coach Trey Hillman spent five seasons as a manager in Japan and two in Korea. Hillman said he’s against the countries’ iteration because ties aren’t included in the standings. Theoretically, Hillman said, a team can win the first game, tie for the rest of the season and finish in first place with a 1.000 winning percentage. He said MLB would have to adopt a points system to give wins more value.

“I remember just like it was yesterday, the feeling that I had being confused when our Japanese players were congratulating each other at the end of the 12th inning and we tied and I asked my pitching coach,” Hillman said. “I said, ‘What are they doing?’ He said, ‘A tie’s better than a loss.’ ”

Players, executives and scouts offered opinions on the tie split along three groups: indifferent, pro, and against.

“Just tradition,” one executive said. “That’s pretty much the only argument against it.”

“I actually like the runner on second,” one scout said. “I would vote for that over ties. I think the runner on second adds some excitement. Much more exciting than just starting an inning clean.”

“I’ve always said ties should be a thing,” Toronto Blue Jays and former Dodgers pitcher Ross Stripling said in a text. “Maybe play a normal 10th inning and then it’s a tie. There are 162 games. [I] find it hard to think it’d really affect standings that much.”

Ross Stripling was stunned when the Dodgers traded him to the Blue Jays. Now he’s rooting for his former teammates and thinking he could have made a difference.

In late April, the Pioneer League went another route, announcing it would settle ties this year not with extra innings, but with a home run derby. Each team designates a hitter to see five pitches. The game’s winner is determined by who hits more home runs. The teams pick another hitter to see five pitches if the round ends in a draw.

In its announcement, the league explained the reason for the change is “to avoid excessive strain on our pitching staffs.”

The home run derby isn’t unprecedented. The Futures Collegiate Baseball League, an eight-team New England summer league, introduced a variation of the home run derby to break ties in 2016. In the FCBL, up to three batters on each team are given three minutes and two timeouts to hit as many home runs as possible. Any member of the team, player or coach, can throw the pitches.

The difference is that the Pioneer League is the first professional league and the first league with a direct relationship with MLB to venture into this territory. The league’s eight teams began their 92-game seasons May 22. Through Wednesday, one game had been decided by the home run derby.

“I’m not a fan of it,” Dodgers manager Dave Roberts said. “I get the fan interest to finish a game with a derby. It is what it is if that’s the rule. But I kind of like baseball determining the outcome of a game.”

Baseball purists scoffed at Justin Turner’s idea decide tie games by a home run derby. But it’s already popular in a New England collegiate summer league.

Dodgers third baseman Justin Turner tweeted his approval of the Pioneer League’s decision within hours of the announcement. It wasn’t the first time he lobbied to use a home run derby as a tiebreaker. Last April, during the league’s shutdown, Turner pushed for MLB to implement the home run derby after the 10th inning as the league contemplated ways to curtail the toll on players in anticipation of a truncated schedule.

MLB instead chose to start extra innings with a runner on second base. The change was initially met with resistance, as with most changes in baseball, but it grew on people within the sport, leading to its adoption in 2021. So far, the format hasn’t helped the Dodgers.

They’re 1-7 in extra-inning games this season, including a nine-inning loss against the Chicago Cubs in the nightcap of a seven-inning doubleheader. At one point, they played five extra-inning games in a 11-game span and lost all five. It could’ve been worse. The longest went just 11 innings. Leon Cadore would’ve appreciated that.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.