Aaron Hernandez conviction: Gambling on risky players is an NFL reality

- Share via

Heading into the 2010 draft, NFL scouts took a long look at Florida tight end Aaron Hernandez, and the red flags were undeniable.

He had first-round talent but also a reputation for frequent marijuana use, a hot temper and an unsavory group of hometown friends who made regular trips to Gainesville, Fla., to visit him.

Hernandez was expected by many experts to be among the top picks at his position, but he dropped to the fourth round, in which he was selected by the New England Patriots, because of concerns about his character.

One team scout, in a 2010 evaluation report obtained by the Boston Globe, said: “Self-esteem is quite low; not well-adjusted emotionally, not happy, moods unpredictable, not stable, doesn’t take much to set him off, but not an especially jumpy guy.”

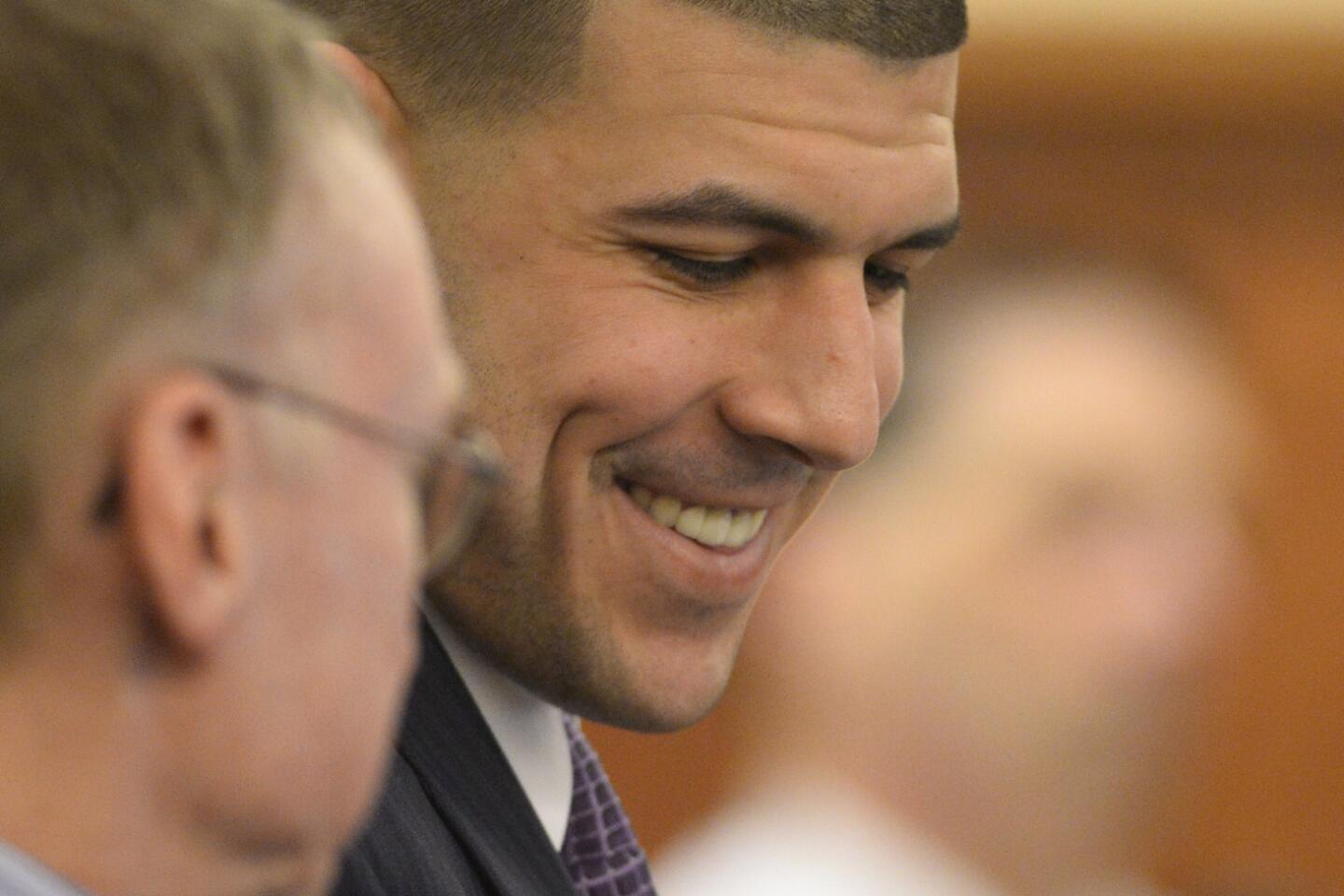

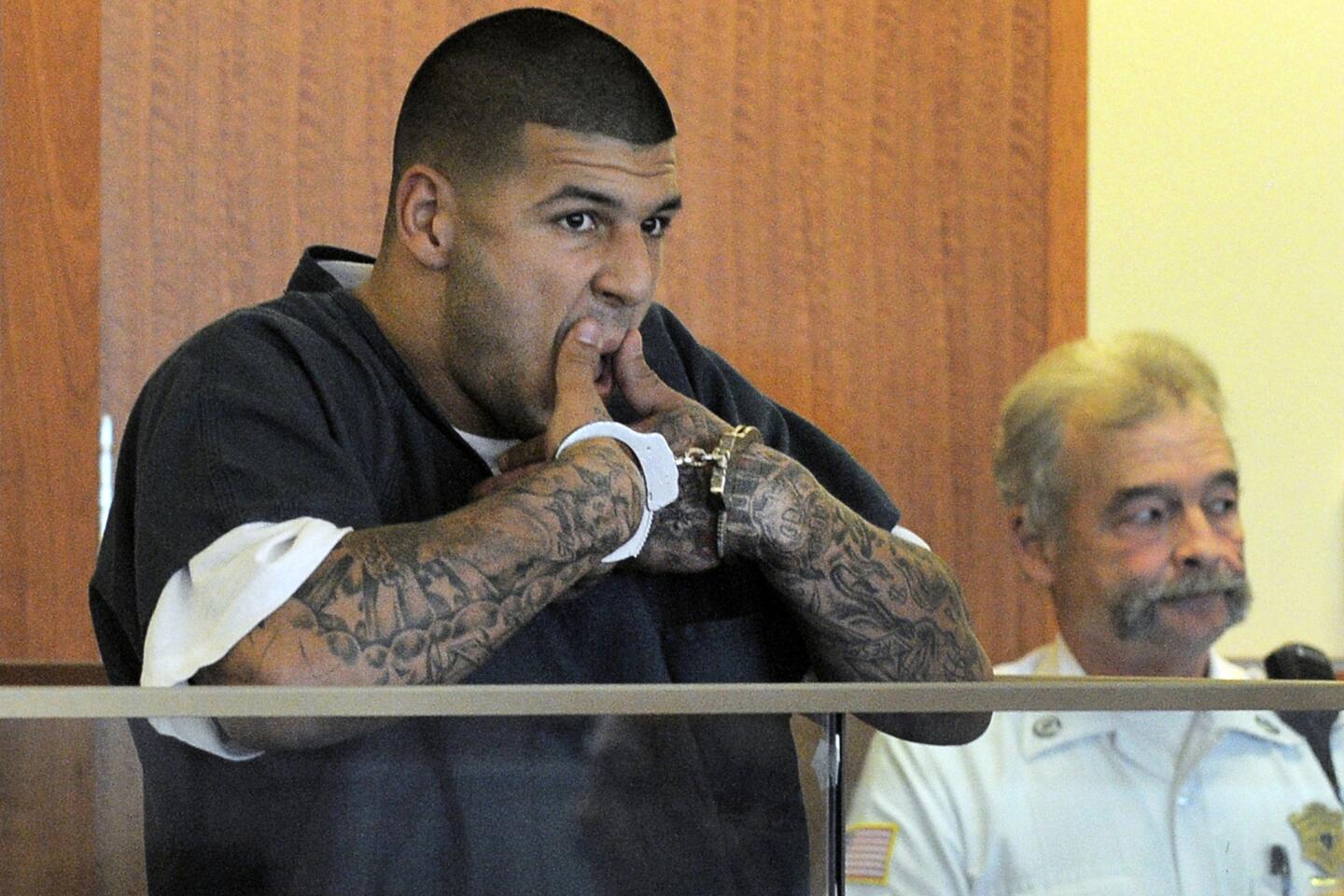

On Wednesday, Hernandez, 25, was convicted of first-degree murder for the shooting death of Odin Lloyd in 2013. The tight end, who earned millions playing for the Patriots, received an automatic sentence of life in prison without the possibility of parole.

The league has long accepted that taking chances on players with character flaws is part of the game. Hernandez is a worst-case scenario, signaling that every team is susceptible — even the ultra-disciplined New England Patriots, who have a reputation of getting the best out of hard-case players.

Every NFL team has players with trouble in their pasts. It’s an unseemly reality in a league in which the pressure to win is high and coaches are supremely confident they can succeed with problem players. The majority of NFL players are good guys, but every locker room has its problem players.

Just this off-season:

• Dallas signed Pro Bowl defensive end Greg Hardy, who was found guilty during a bench trial of assaulting and threatening to kill his girlfriend. (Charges were dismissed upon appeal when Hardy’s girlfriend failed to testify.)

• Buffalo signed Pro Bowl guard Richie Incognito, the main instigator in the bullying of a Miami Dolphins teammate.

• Denver Pro Bowl cornerback Aqib Talib, who has a history of physical altercations and arrests, is being investigated for his involvement in a fight outside a Dallas nightclub that included the firing of a gun.

All this followed the NFL’s most turbulent season, when the off-the-field transgressions of Ray Rice and Adrian Peterson overshadowed the games. Rice had punched and knocked out his then fiancé in an incident caught on casino surveillance cameras; Peterson was accused of child abuse after admitting to hitting his son with a switch.

“I thought this was going to be a very important off-season for the NFL to shore up brand and image, and to project a new responsiveness to these issues going into next season,” said Dan Hill, who works for a Washington, D.C.-based crisis communications firm. “But they’ve been hit with so many issues. … They can’t catch a break.”

Another public relations challenge lies ahead. Florida State quarterback Jameis Winston, who is expected to be selected No. 1 by Tampa Bay in this month’s draft, is another high-risk, high-reward talent. He was accused (though never charged) of sexual assault, arrested on suspicion of shoplifting crab legs and suspended for standing on a table in his school’s student union and screaming obscenities directed at women.

“You’re not going to have all choir boys on your team,” Cleveland Browns Coach Mike Pettine said.

The Browns understand that more than most. A year ago, they used a first-round pick on Texas A&M quarterback Johnny Manziel, whose free-wheeling style of play and history of partying were concerns. He turned out to be a flop on and off the field, and spent part of the off-season in a treatment facility that specializes in drug and alcohol rehabilitation.

It’s not as if the Manziel experience has caused the Browns to dramatically alter how they evaluate prospects, though.

“You don’t want to have a knee-jerk reaction and say there were some things that happened to us, so now all of a sudden anybody with that type of background issue is instantly off our draft board,” Pettine said. “That would be a pretty thin draft board.”

Rex Ryan, the new coach in Buffalo after six seasons with the New York Jets, brought Incognito on board, along with the volatile Percy Harvin. Seattle was more than happy to unload Harvin last season, trading him to Ryan’s Jets for a late-round draft pick after the receiver had multiple fights with teammates.

“Teams want players to play with rage, utter rage, blind rage,” said Jody Armour, a USC law professor. “So the players are socialized that way. We stoke these particular gladiators and then we’re shocked when those passions go beyond the gridiron and then start to spill over into everyday social life.”

Hernandez and Harvin were teammates on Urban Meyer’s Florida team before they were drafted.

“There’s not one person that’s perfect, and that’s you, me, everybody else sitting here, and everybody in the locker room,” Ryan said last month at the NFL owners meetings when asked about Harvin and Incognito. “People make mistakes. But we feel great about both of those guys.”

If a player is talented enough, and can stay out of jail, there is an NFL team for him. Hardy is a prime example, signing a one-year deal worth $11.3 million. His guilty verdict in North Carolina for beating his girlfriend was set aside when he requested a jury trial. Eventually, after receiving a financial settlement, the woman refused to cooperate with the district attorney’s office and the charges were dropped.

Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings was among those sharply critical of the Cowboys after the signing.

“I’m a big Cowboys fan; I love them to death and I want them to beat the Eagles every time they play,” Rawlings told reporters last month. “But at some point, being a sports fan gets trumped by being a father, husband, wanting to do what’s right for women, so this is not a good thing. I don’t think I’m going to be buying Hardy jerseys any time soon.”

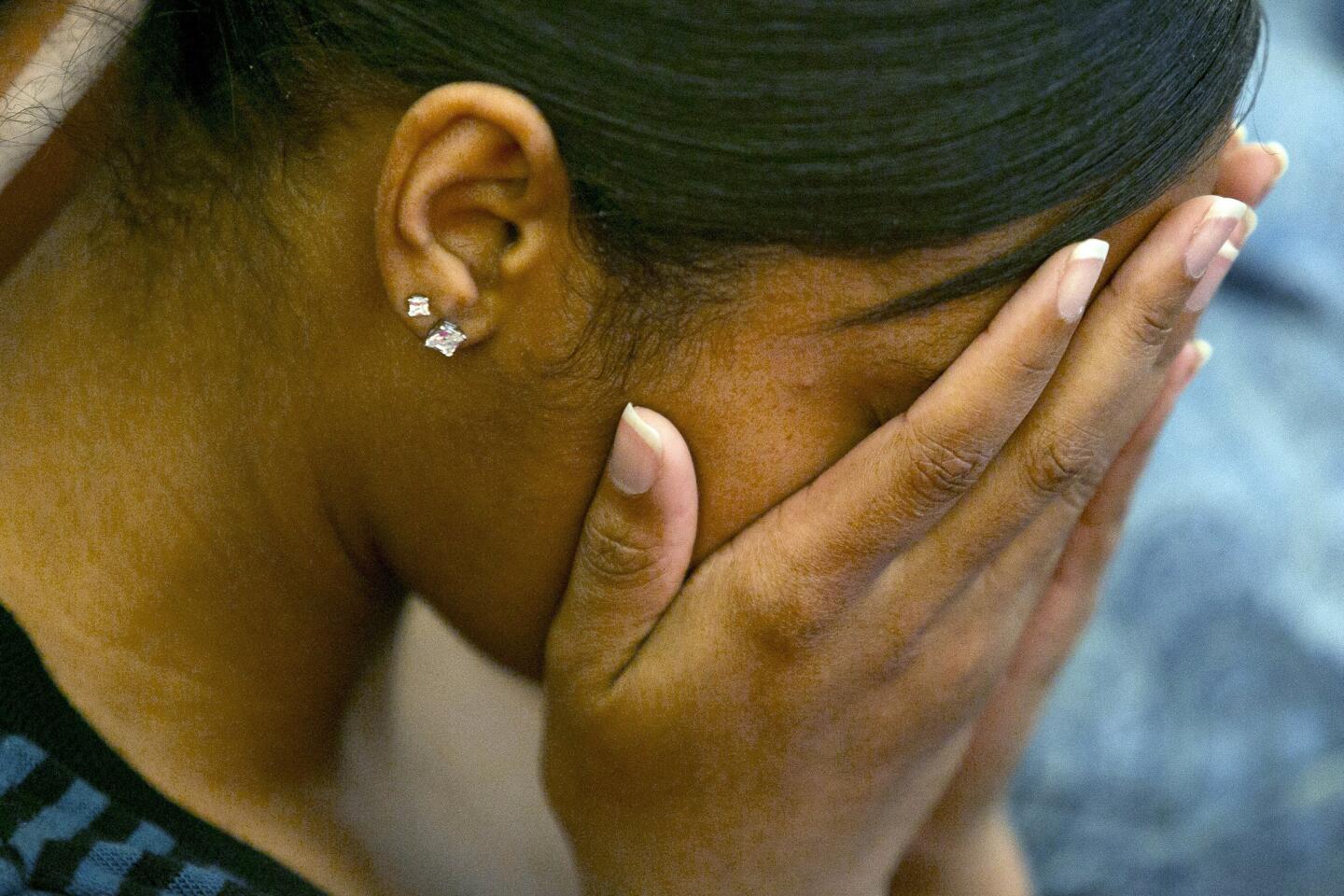

Hernandez was convicted Wednesday after a jury deliberated for 35 hours in Bristol County Superior Court in Fall River, Mass. The jury ruled he had acted with “extreme atrocity or cruelty” in the slaying of Lloyd, a 27-year-old semi-professional football player who was dating the sister of Hernandez’s fiancé. The body of Lloyd was found shot six times in an industrial park near Hernandez’s home.

The prosecution never gave a clear picture as to why Lloyd was fatally shot other than indicating that things escalated after Hernandez believed he was disrespected or betrayed by Lloyd.

Hernandez had signed a five-year, $40-million contract extension with the Patriots the summer before the slaying. Next, he will stand trial in a separate case, a 2012 double killing in Boston.

Twitter: @latimesfarmer

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.