Augusta National presents unique challenges for Masters photographers

- Share via

Reporting from augusta, ga. — They are on the outside looking in — and for sports photographers covering the Masters, that’s all part of the challenge.

Among the many unique elements of the storied golf tournament is that photographers and other media members do not have inside-the-ropes access, so it’s far more challenging to get into prime position to see the action, especially when there’s a strict no-running rule at Augusta National.

“Every other tournament you cover — I’ve covered the British Open, Ryder Cups, the U.S. Open and the PGA Tour — you’re inside the ropes,” said Reuters photographer Brian Snyder, who has covered every Masters since 2006. “So that’s easy: pin, ball, photographer — make a line. It’s not rocket science.

“But here you can’t do that because you’re not inside the ropes. So you need to know before coming to the hole, you have to have an idea where you’re going. You don’t have time to spend thinking about it. It’s too crowded.”

Seasoned photographers working the Masters, typically shouldering 20 to 30 pounds of equipment, often make a beeline for high ground when they approach a hole, know all the shortcuts to get around the course and are experts at sweet-talking spectators — known as “patrons” in these parts — to move over just a smidge.

“You learn different tricks for every hole,” said Curtis Compton of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, who has covered 30 Masters. “When Tiger Woods came along, and you’ve got like 20,000 people following him from hole to hole, the only way you could cover him is with radios and hop-skipping the holes. I’ll get him this hole, you get him the next, I’ll get him the hole after that.”

When working as a group — Reuters has a team of four on the course, for instance — photographers communicate with radios and are deathly afraid of their earpieces coming unplugged if jostled in a crowd. That could lead to a disruptive and humiliating chirp of the device, and that happens from time to time.

Experienced golf photographers know not to snap shots when a player is standing over his putt, or during his backswing. But sometimes the camera has a mind of its own.

“Years back, I had a camera on my shoulder and it just started going off,” Compton said. “It shorted out. I took it off and threw it on the ground, and it’s over there like womp-womp-womp-womp running.”

Sometimes those malfunctions are caused by rain, which presents an entirely different headache for photographers.

“When it rains, all the umbrellas come out,” said Mike Blake, a Reuters photo editor. “That’s another worst nightmare.”

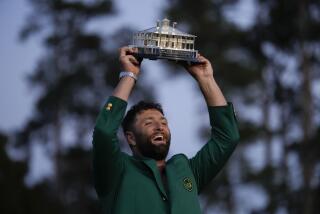

Make no mistake, these people love their jobs. They get to witness sports history and document it for the world, sometimes in a more enduring and artistic way than television.

Sign up for our daily sports newsletter »

“The course is part of the story here,” Compton said. “You’re not just shooting golfers. The beauty of the golf course is always part of it. So your images aren’t just tight sports action.”

Unlike a U.S. Open, World Series, Olympics or Super Bowl, the Masters happens in the same place every year. In many ways, the spectacular course is the star.

“You could send a picture with the golfer the size of a little ant, and anyone will say, ‘That’s Augusta,’” Blake said. “The golf course is sometimes more important than the golfer, and where does that happen in any other sport?”

The photographers know the ins and outs, tricks and hacks around the grounds. For instance, although they’re not allowed to use phones to transmit their images from the course, there are some secret stations at a few spots — hidden behind walls and camouflaged with green paint — where photographers can upload their photos to the media center (and nowhere else) via an ethernet connection. That allows them to keep working with minimal interruption.

On Monday, when they encountered each other during a practice round, Compton delivered some bad news to Snyder: They could no longer enter the restrooms through the exit door, thus circumventing the line. That had been tradition.

“You’ve got to be hydrated out here, but you can’t over-liquify,” Compton said. “Somebody told me that if you can’t hold it for eight hours, you’d never make it as an [Associated Press] photographer.”

Then there’s the schmoozing and finagling to get the lens into position. Sometimes it requires lifting the camera high overhead, in what’s called a Hail Mary move, while for others, it’s kneeling for a low angle through a forest of legs.

“For very popular golfers and on the 18th hole, you have to run up at the last minute and it’s completely full of golf fans, some of them there all day in their chairs,” said Lucy Nicholson, another Reuters photographer.

“But the nice thing about people not having cellphones on the course is they talk to other people more often. So people seem friendlier sometimes than at other tournaments. So on every hole almost, you’re having a conversation with somebody and talking your way into a spot.”

The key for these photographers is to notice everything … yet not be noticed.

“The golfers shouldn’t know you’re there,” Snyder said. “If they notice you, you’ve probably done something wrong.”

Twitter: @LATimesfarmer

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.