Must Reads: He was a first-round draft pick in the NBA. 14 years later, he was found dead. Who killed Lorenzen Wright?

- Share via

Sherra Wright guided the silver Cadillac SUV through the darkness on a mild night, seven years after search and rescue dogs found her ex-husband’s body in a Memphis field.

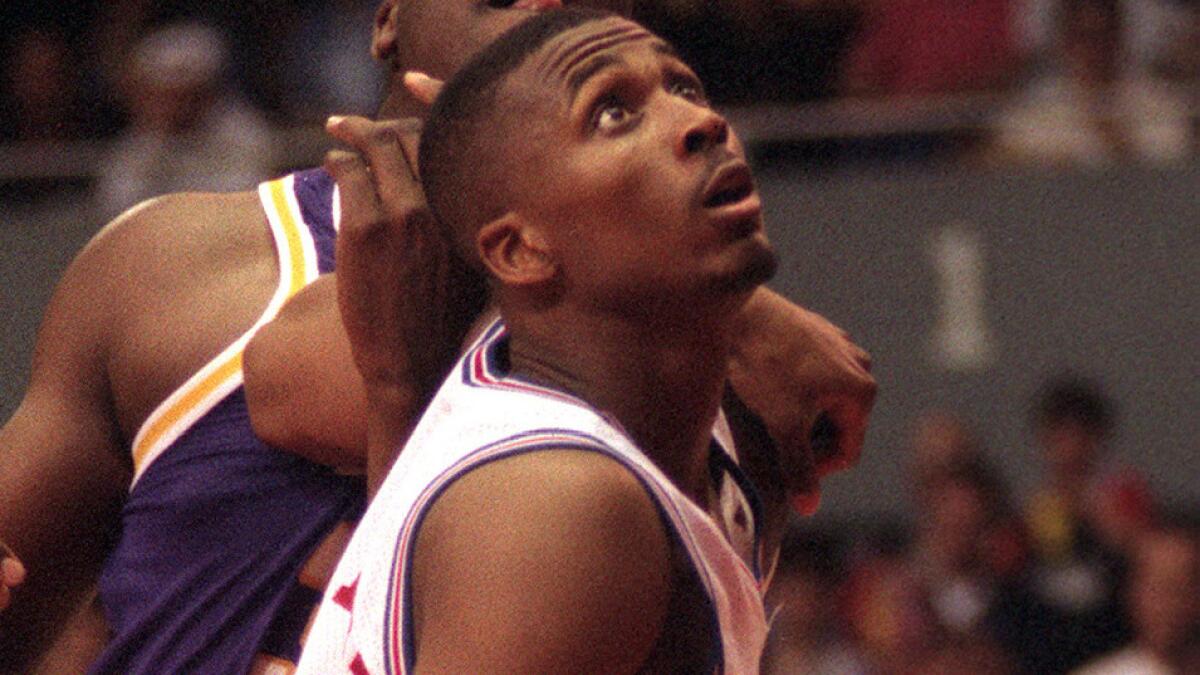

The remains of Lorenzen Wright weighed 57 pounds. The coroner needed dental records to identify the man the Clippers had picked in the first round of the 1996 NBA draft. Five gunshot wounds were visible in the withered corpse. Two in the head. Two in the torso. One in the right forearm.

The killing remained unsolved, but by last December a long-dormant police investigation had taken on new life. And a task force of federal marshals and Riverside County sheriff’s deputies was tracking the Cadillac on Interstate 15 near Norco.

As Sherra drove south with her twin 17-year-old boys, Lamar and Shamar, she relived the Murrieta Mesa High basketball team’s five-point win earlier that night. The twins combined to score 32 points. Sherra told her oldest son, Lorenzen Jr., all about the game on the phone.

Then red and blue lights flashed behind them. The SUV pulled over and a voice amplified by a loudspeaker ordered Sherra to exit the car with her hands up. She started shaking.

More cruisers zoomed up. Guns were drawn, Lamar said. The twins begged their mother to keep her hands up.

They met about 25 years earlier, the teenage basketball prodigy from small-town Mississippi still growing into his 6-foot-11 body, and the headstrong daughter of his club coach.

Lorenzen was 16, Sherra five years older. She paid for his hot wings and iced tea on dates, as well as for better clothes, new shoes, even a custom-made suit.

“It was love and hate at the very first sight,” she wrote in “Mr. Tell Me Anything,” a 2015 book featuring two characters she later said were based on her and Lorenzen. “He hated that she was all he had been warned she would be. She hated that her interest was officially sparked by a minor.”

This story is based on interviews with three of the couple’s six children — the first time they’ve spoken publicly — and others close to the family in addition to court documents, books, public records and media accounts.

“Ours is a Love Story, not this horror film that has been erected by the Media,” Sherra wrote in a brief letter to the Los Angeles Times.

Nicknamed “The Howl” because he screamed after dunking the ball or blocking a shot, Lorenzen earned $55 million during 13 seasons with the Clippers, Atlanta Hawks, Memphis Grizzlies, Cleveland Cavaliers and Sacramento Kings. Friends thought the couple put on a good show off the basketball court: the stay-at-home mother and doting father enjoying mansions, luxury automobiles, designer clothes and a family that always appeared to be smiling.

After the Clippers drafted Lorenzen from the University of Memphis with the seventh overall pick in June 1996, Ian Rice became close friends with the young family adjusting to Los Angeles.

Then a teenage ballboy for the Clippers, Rice helped Lorenzen and Sherra move into a custom home in Playa del Rey and cared for their Rottweilers. Lorenzen lent the kid his Chevrolet Tahoe with televisions and a video-game system in the back for prom, then bought him a tuxedo and Nikes to match the cherry red SUV. When Rice graduated from high school, Lorenzen and Sherra attended the ceremony and rented him a limousine with a “Class of 1999” banner.

“He was in love with her,” Rice said. “She had a grip on him.”

But privately there was trouble, which occasionally spilled into public view. In August 2005, police responded to a domestic disturbance call at the Wright’s Memphis home. Sherra, according to news reports at the time, had a cut hand and abrasions on her jaw. There were no arrests or charges.

Another time, Lorenzen and childhood friend Mike Gipson retreated to the family’s RV with a couple of strippers. Sherra discovered them, Gipson said, and Lorenzen jumped out a window. Sherra forced her way into the RV, chased the strippers out, ripped off Gipson’s shirt and tore up the vehicle’s interior.

A handful of violent incidents between the two main characters in “Mr. Tell Me Anything” are folded in with allegations of infidelity and explicit descriptions of sexual encounters. Sherra told the Memphis Commercial Appeal in July 2015 that “99.99 percent” of the book contained true stories from her relationship with Lorenzen. She described it on social media as “my story.” Lorenzen Jr. said his mother “wrote about things that really happened in her life.”

The book described the wife catching her husband with another woman. The wife kicked down the bathroom door, dragged the interloper out by her hair and repeatedly punched her. Then the wife turned to her husband and “slapped the hell out of his ass.”

Lorenzen and Sherra separated in early 2009, around the same time his NBA career ended. Banks foreclosed on two of their homes, including a 17-room mansion in Eads, Tenn. They had $3 million in joint debt.

A permanent parenting plan filed in Shelby County, Tenn., Circuit Court before the divorce was finalized in February 2010 required Lorenzen to pay $26,650 a month in alimony and child support based on his previous income as a professional basketball player. It cited the couple’s “extremely lavish lifestyle” and the need to continue to provide the children with benefits like a nanny and private basketball training.

Lorenzen also had to maintain a $1 million life insurance policy, with Sherra as trustee.

Document

E. LIFE INSURANCE If agreed upon by the parties, the father shall insure his own life in the minimum amount of $ ONE MILLION DOLLARS by whole life or term insurance. Until the child support obligation has been completed, each policy shall name the child/children as sole irrevocable primary beneficiary, with the other parent, as trustee for the benefit of the child(ren), to serve without bond or accounting.

see the documentA few months after their divorce, the relationship seemed to have thawed. Loren, the couple’s oldest daughter, said her father wanted to remarry Sherra.

“He would tell us every day he was working to win her back,” the 21-year-old said.

Investigators later found a series of sexually explicit text messages Sherra sent Lorenzen on July 17, 2010 — designed, they said in court records, to lure him to Memphis.

Lorenzen flew from his home in suburban Atlanta the next day without even packing a change of clothes.

Phil Dotson, a close friend, later told reporters he dropped off Lorenzen and Lorenzen Jr. at Sherra’s rented home on Whisperwoods Drive in the Memphis suburb of Collierville around 10 p.m. Nothing seemed amiss.

Lorenzen planned to drive back to Atlanta with a friend, Jeremy Orange, and the children on July 19. The trip would include a stop at Six Flags White Water, Orange said. When he arrived at Sherra’s home that morning, she said Lorenzen wasn’t there. Orange repeatedly called his friend. There was no answer.

When Gipson called Sherra, she suggested Lorenzen had run off with a lady friend. She texted Orange that Lorenzen was “probably in one of his little holes” and ended the message “LOL.”

Lorenzen’s mother, Deborah Marion, filed a missing persons report July 22. When officers contacted Sherra, she told them her ex-husband left the home around 2 a.m. on July 19 with an unknown person in an unknown vehicle.

Police sifted through a slew of theories on Lorenzen’s whereabouts. Sherra suggested Las Vegas. His father, Herb Wright, thought Lorenzen was in Europe “getting his mind right.” Others guessed Lorenzen had flown to Israel for a basketball tryout.

A week after her ex-husband vanished, Sherra fought tears as she spoke with reporters at her front door: “I’m not going to believe anything other than he’s fine now.”

The next day, she told detectives that Lorenzen had been involved in “major criminal activity,” after previously telling them he didn’t have any “problems, concerns or enemies.” She said he left her home late on July 18 with a box of drugs and cash. Several weeks earlier, Sherra added, men in a car with Florida license plates had come to the house looking for Lorenzen.

In a separate conversation with detectives that day, Marion said her former daughter-in-law was “acting odd.”

On July 28, Sherra told detectives Lorenzen made a phone call before leaving her home around 11:30 p.m., saying he was going to “flip something for $110,000.”

By then, police had linked Lorenzen to a brief 911 call made at 12:05 a.m. on July 19. The call had been lost for nine days in the confusion of overlapping jurisdictions. Police tracked it to an overgrown field surrounded by woods in Memphis — a spot Lorenzen, Sherra and friends visited over the years to drink, talk out quarrels, relax.

Authorities discovered his body there, along with his necklace, watch and shell casings from two guns scattered on the ground.

In the call, Lorenzen sounded overwhelmed by confusion and terror.

[Bang! Bang!]

Lorenzen: “Hey, goddamn!”

Operator: “Germantown 911. Where's your emergency?”

[Bang!]

Operator: “Hello?”

[Bang! Bang!]

Operator: “Hello?”

[Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang!]

Operator: “Hello? ... I don't have nothing but gunshots."

Lorenzen’s body and nearby evidence spent 10 days exposed to 90-degree temperatures and a half-inch of rain. The remains were essentially a skeleton.

“It was pretty much a cold case by the time investigators got it,” said Toney Armstrong, a Memphis Police veteran.

Four days after the discovery of Lorenzen’s body, police searched Sherra’s home. Neighbors told them about an unusual bonfire in her backyard a night or two after Lorenzen disappeared. She retained a criminal defense attorney.

Thousands attended Lorenzen’s memorial service at FedEx Forum in downtown Memphis. The silver casket rested in front of the stage among a sea of photos and flowers. Coaches, pastors, relatives, politicians and former NBA players testified to the special bond between Lorenzen and Memphis during his 34 years:

“He had unlimited potential.”

“This boy, young man, was an icon to the city.”

“There’s gonna be rumors. There’s gonna be hearsay. But God knows the truth. And they will have to stand before the Lord.”

The $1 million in life insurance money arrived 14 months after Lorenzen’s death.

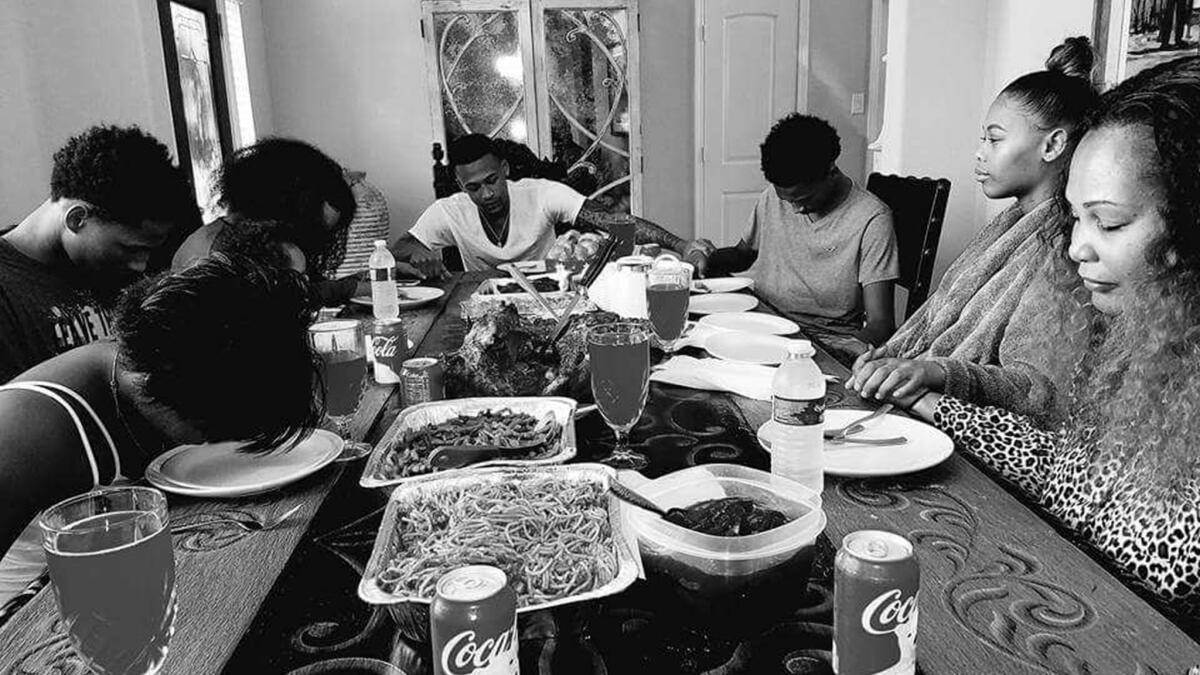

One of the first expenses, according to court records, was $1,445 for Lorenzen’s headstone engraved with a cross and basketball. After that, Sherra bought almost $70,000 of furniture and a Cadillac, Mercedes and Lexus. She acquired a 5,300-square-foot house in foreclosure. She put $7,100 down on a swimming pool and spent $11,750 for a family trip to New York.

Sherra made cash withdrawals or wrote checks to herself for more than $344,000. She spent most of the life insurance money in the first 10 months, the records show.

“All that money she so-called blew, it wasn’t spent on anybody else, it was spent on us,” Lorenzen Jr., now 23, said in a recent interview. “She don’t care about anything else but her kids.”

A court filing in 2014 excoriated Sherra for a “lack of prudent financial judgment.” Just $5.05 remained in the trust’s bank account.

Meanwhile, the investigation into Lorenzen’s death stalled. Memphis CrimeStoppers received only a handful of tips. The reward money remained modest, starting at $6,000 before reaching a high of $21,000.

Armstrong, the Memphis Police director from 2011 to 2016, said he received phone calls suggesting police look into Sherra. A grand jury questioned her, but no charges were filed.

“The entire city wanted that homicide solved,” Armstrong said.

Sherra helped start a charity for inner-city children called Born 2 Prosper; the IRS revoked the organization’s nonprofit status in 2013 for not filing returns. She became a minister at Mt. Olive No. 1 Missionary Baptist Church in Collierville and rehearsed sermons in front of her children. She married Shelby County Sheriff’s Deputy Reginald Robinson in March 2014.

“Over the past few years I have been called all sorts of things including crackhead, gold digger, stripper, murderer, whore and all other various terms,” Sherra wrote on Facebook in January 2015. “I gave it ALL to God and HE worked it out and works it out!”

A reporter named Kelvin Cowans met Sherra in a Memphis-area Starbucks early in 2015. He planned to write a story for a weekly newspaper marking the fifth anniversary of Lorenzen’s death. During the interview, Sherra denied having anything to do with the killing and assailed her treatment by local media and relatives who suspected her involvement.

“That bothered me — that the first time they would try to find out who I was would be when they are trying to tie me to a murder of somebody I’ve spent half my life with; somebody that I loved more than myself,” Sherra told Cowans in an interview he recorded. “That was so hurtful.”

The six-hour discussion ended only because the coffee shop closed, he told The Times. They started dating within a week or two. Sherra divorced Robinson a few months later and eventually moved with Cowans to a white brick home in Sugar Land, Texas, with five of her six children. Lorenzen Jr. had left for college.

Sherra cheered her children during high school basketball and volleyball games. The couple watched “Game of Thrones” and “Grey’s Anatomy.” And Cowans said Sherra kept spending: a gray Jaguar, a BMW, $15,000 for Christmas. Even after the insurance money ran out, she had property and other assets left over from the marriage to Lorenzen.

Not everything was normal. Cowans recalled that Sherra sometimes paced the street in her bathrobe while shouting into her phone. He couldn’t figure out what precipitated such intense conversations and tried to block them out.

A few nights each week, Sherra retreated to the couple’s walk-in closet to pray, usually with a pillow and blanket. Most of the closet belonged to her: mink coats, Rolex watches, about 300 pairs of shoes, more than 200 purses and an abundance of designer clothing. Cowans sometimes heard crying and incomprehensible speech coming from the closet.

On one occasion, Cowans said, Sherra walked into their bedroom in the middle of the day, played Lorenzen’s 911 call and asked if he thought an indistinct voice on the recording sounded like a man or woman.

“She’d have this scared look on her face,” said Cowans, who later split with Sherra and wrote about their relationship in the book “The Whispering Woods of Sherra Wright.”

Repeated court fights with Herb Wright, the executor of Lorenzen’s estate, kindled Sherra’s anger. In one clash, she alleged Lorenzen didn’t make alimony and child support payments before his death and petitioned Shelby County Circuit Court in February 2016 to take the money from the estate.

“Lorenzen’s family questioning her about anything would always set her off. … It was real bad. It was just ugly,” Cowans said. “Looking back, now I believe Sherra felt like Lorenzen wronged her so it really didn’t matter how she treated him or his family.”

Sherra bolted awake one night breathing heavily. She usually didn’t talk to Cowans about the constant nightmares.

This time, though, she said Lorenzen had called her down a street in their old neighborhood.

“You know I love you,” Lorenzen said. “Get over here.”

He reached out, she said, and crumbled into dust.

Sherra and Cowans broke up in February 2017. She and the children moved to Riverside County, where her brother, Marcus Robinson, worked as a pastor.

Tim Robertson, an old friend, became her third husband. They settled in Murrieta. Loren learned about the marriage when Sherra mentioned it during a casual phone conversation.

Sherra ferried the younger children to practices and games, hosted their friends, retweeted basketball highlights from the twins and finished writing the sequel to “Mr. Tell Me Anything.”

When she floated the idea of pursuing a job providing in-home medical care, the children recoiled. She had been a stay-at-home mother their entire lives. They didn’t want that to change.

“I know how much she has sacrificed over her whole life just trying to protect us and make sure we’re OK,” Lorenzen Jr. said.

Unknown to the family, the hunt for Lorenzen’s killers had taken on new life. The Shelby County Multi-Agency Gang Unit received an unspecified tip in spring 2016 that led it to reexamine the case. Officers dubbed the effort Operation Rebound because it was a second chance to bring closure to Lorenzen’s family. They investigated the murder as if it had just occurred, even retracing his final steps in the field.

Each tip and piece of evidence pointed to a murky lake next to a landfill in Walnut, Miss. It had been searched without success earlier in the investigation after a tip from one of Sherra’s cousins, Jimmie Martin. Investigators tried again.

On June 27, 2017, an FBI dive team found a semiautomatic 9-millimeter Smith & Wesson pistol in the lake. Ballistics testing matched the shell casings near Lorenzen’s body.

About four months later, investigators secured a court order to monitor Sherra’s phone calls. They announced the pistol had been found, then intercepted a call by Sherra that seemed to imply an informant led authorities to the weapon.

“Someone done sent somebody somewhere to get something,” she said in the call.

Cowans texted. He thought Sherra would be relieved the pistol had been found. Instead, she sounded worried, even agitated. He didn’t know what to make of the response.

Four days after the intercepted call, investigators said, Sherra flew to Memphis and met with Billy Ray Turner — a convicted felon who served as a deacon at the Collierville church she once attended. A relative of Sherra told investigators the ex-wife and Turner were in a romantic relationship at the time of Lorenzen’s murder. Loren disagreed.

“He was not my mom’s secret lover,” she said.

Turner had also been named in Lorenzen’s death in 2010 by two tipsters to Memphis CrimeStoppers. It is not clear why those tips didn’t advance the case.

(Speaking generally at a news conference about the case last December, Memphis Police director Michael Rallings said tips don’t always give authorities sufficient evidence to make an arrest.)

In another intercepted phone call, investigators overheard Sherra tell an unknown person that when police searched the home on Whisperwoods Drive in August 2010, they missed three guns.

Police arrested Turner in Collierville on Dec. 5. A week and a half passed before the task force pulled over Sherra’s Cadillac SUV on Interstate 15 in Norco.

The twins started crying, Lamar recalled. They had no idea what was happening. Officers removed the children from the Cadillac one at a time. They seated Lamar in the back of a cruiser. An officer told the boy they were arresting his mother for killing his father.

The prosecution’s case centers on Martin, an aspiring Memphis rapper who used the stage name Triksta. He is also Sherra’s cousin.

In addition to providing the tip about the pistol in the lake, Martin alleged that Sherra paid him and Turner in a failed attempt to kill Lorenzen to collect the life-insurance money. According to the complaint, the men tried to kill Lorenzen at the suburban Atlanta townhouse in early 2010. They entered through a window Sherra left unlocked, but Lorenzen wasn’t there.

After Lorenzen's death in July 2010, Martin told authorities, Sherra and Turner had “confessed to him that they had murdered Lorenzen Wright.”

Martin is serving a 20-year prison sentence for second-degree murder in the shooting death of his girlfriend. He didn’t respond to an interview request through his attorney.

Sherra and Turner have pleaded not guilty to first-degree murder charges. Five years passed between Martin’s tip about the gun and their arrests.

Most of the case file is sealed, the people involved remain tight-lipped and prosecutors haven’t offered an explanation for the delay.

An orange jailhouse shirt had replaced Sherra’s designer clothes in late January when she arrived in Memphis after a cross-country trip in a prison transport bus.

During a hearing May 30, Shelby County Judge Lee Coffee read a series of reports about Sherra’s behavior in jail. The previous day, the judge said, she directed “abusive, profane language” toward guards. Coffee described the words as “so foul, so offensive, so incendiary that I will not even publish these statements in this courtroom.”

Six minutes after the outburst, she allegedly stripped naked and attempted to stuff items into a toilet to flood the cell. The judge said she told guards she was “going swimming, y’all.”

One of Sherra’s former attorneys, Blake Ballin, suggested at the time the incident raised concern about her mental health. The judge increased Sherra’s bail to $20 million.

“It’s all like a terrible dream, all of it,” Sherra, now 47, wrote in the letter to The Times delivered by Loren. “From his murder to my arrest, unreal. But, I have grown as a woman of God that is putting my hope in the Lord. I believe, with the help of the nation, I will make bond. … I can’t wait until the day that I sit down for a ‘real’ documentary or movie with the TRUTH in it.”

The letter ended with a plea for supporters to write her in jail, raise bail money and buy the sequel to “Mr. Tell Me Anything.”

“Stay tuned for my upcoming book during the Christmas holiday,” Sherra wrote. “Be blessed.”

On Aug. 22, Coffee ordered Sherra to undergo a mental evaluation. No trial date has been set.

Her new attorney, Juni Ganguli, said his client “misses her children terribly” and maintains her innocence.

The six children — who range in age from 11 to 23 — are adamant their mother was not involved in their father’s death.

“Not my mom, not Sherra,” Loren said.

The children created a GoFundMe in late June to help bail out their mother. The “Bring Mommy Wright Home” campaign, seeking $500,000, accused prosecutors of “having no case other than lies and fabrications.”

More than two months later, it hadn’t raised a dollar.

Twitter: @nathanfenno

Additional credits: Produced by Justin L. Abrotsky.

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.