Amid the protests, college football players, and top recruits, find their voices truly matter

- Share via

Fueled by a sense of empowerment that had been growing for weeks, Ceyair Wright opened his Twitter app Wednesday night. He had something to say, and, as one of the top uncommitted football recruits in Southern California, he would have no problem corralling an audience once he sent the alert.

“8:46 am tmr,” he thumbed into his iPhone, accentuating the tweet with a black heart emoji.

Within seconds, the replies from Wright’s followers poured in. They were not seeking further enlightenment about the reference to the amount of time Derek Chauvin had his knee on George Floyd’s neck. Instead they were rapt with anticipation that the Los Angeles Loyola High cornerback might be committing to their favorite college the next morning at 8:46.

Fans from USC, Oregon and Notre Dame weighed in, begging the 17-year-old to pick their school.

“I didn’t even think people would take it as a commitment thing,” Wright would later say.

When Thursday morning came, those fans learned that Wright had in fact made a decision — just not the one anyone expected. He had chosen to use his voice for the first time.

What started as a talk with his father, Claudius, at the kitchen table had blossomed into a video featuring Ceyair and 17 other top L.A. area football prospects, speaking out against police brutality and racism.

“Throughout history,” Ceyair begins, “African-Americans have faced seemingly unsurmountable adversities. We’ve been beaten, killed and discriminated against.”

“Eight minutes and 46 seconds to change the world,” follows Corona Centennial defensive end Korey Foreman, the No. 1 recruit nationally in the 2021 class.

“We will never be the same,” two others repeat.

“Watching a man’s life escape his body lying face down in the street … calling for his mother … I saw my father, my brother, myself,” three players read from the script.

Claudius had penned the other players’ lines, but not his son’s. Ceyair, an aspiring actor who played LeBron James’ son in “Space Jam: A New Legacy,” felt plenty comfortable in his own skin.

“Making it home safely shouldn’t be a thought on my mind,” Ceyair says, “but sadly it is for people across the country who look like me. The time is now to change.

“I am George Floyd.”

“We are George Floyd,” the rest of the players respond.

Ceyair’s college choice would have to wait for another day. The only pledge he and his friends were ready to make Thursday was one to “steer society in a new direction.”

His head-fake, while unintentional, was fitting in a way. A player is never as powerful as the moment before he or she picks a school. But once the national letter of intent is signed, leverage transfers to the school and its coaching staff with one sweep of a pen. For the next three to five years then, depending on the length of one’s stay on campus, players live by the code that one must silence himself or herself for the good of the program.

By speaking up about Juneteenth, Dodgers ace Clayton Kershaw underscored the importance of white athletes taking a stand that Black lives matter.

College football — and football as a sport in general, with its militaristic ethos — has never been a safe haven for activism. But the next generation of players now sees a window for real hope that won’t be snuffed out like that of their predecessors.

With the Black Lives Matter movement holding the country’s attention in the aftermath of Floyd’s death while in police custody, there’s a growing list of new role models popping up nationwide:

At Florida State, defensive tackle Marvin Wilson called out head coach Mike Norvell on Twitter after he said Norvell mischaracterized how the coach handled BLM discussions with his players.

“This is a lie,” Wilson tweeted, threatening to lead a team boycott of Florida State’s voluntary workouts.

The next day, Norvell apologized, and the Seminoles met to begin healing the wounds.

At Clemson, which houses slave owner John C. Calhoun’s plantation as a National Historic Landmark on its campus, Tigers players organized a peaceful protest and pulled in head coach Dabo Swinney, who was under fire for not taking alleged racism within his program seriously, to participate. Days after being ridiculed for wearing a “Football Matters” T-shirt, there was Swinney, publicly speaking on his willingness to learn as a white man in the time of Black Lives Matter.

At Oklahoma State, star running back Chuba Hubbard followed Wilson’s lead, tweeting his disgust at seeing that head coach Mike Gundy had been wearing a One America News Network T-shirt while out fishing. OAN, a news channel endorsed by President Trump, had been dismissive of Black Lives Matter.

“I will not stand for this,” Hubbard tweeted. “This is completely insensitive to everything going on in society, and it’s unacceptable. I will not be doing anything with Oklahoma State until things CHANGE.”

Within a few hours, Hubbard and Gundy appeared together in a video posted on social media in which Gundy said, “I’m looking forward to making some changes, and that starts at the top with me.”

Decisive moves like Wilson’s and Hubbard’s used to be reserved for pros. It had to be the LeBrons who showed young athletes the way.

“It speaks to the bravery of the student-athletes, and I think these brave stands will be even more inspiring than the stands of professionals, who perhaps if everything would be taken from them with respect to their jobs would still be fine,” said N. Jeremi Duru, a sports law professor at American University. “When you have student-athletes coming together against the injustice, it sparks all those that are watching the athletes perform, all those who idolize the athletes, generally younger, to start to take up the cause as well.”

The recruiting class of 2021 will be the first test case. These players now share a purpose with guys who are already in college programs, exercising underused muscles.

When Texas football players made demands last week for the school to remove building names and monuments that have connections to racism, there is a reason that their threat of choice was to discontinue the practice of players hosting recruits. UCLA players chose the same leverage point in their demands, released Friday by the Los Angeles Times, for further protection in their return to campus during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Thirty UCLA football players are demanding that certain measures for coronavirus protection be adopted or they will boycott recruiting activities.

What those Longhorns and Bruins knew is this: No program is going to win without the ability to consistently recruit Black athletes.

“This is going to revolutionize recruiting,” said Paul Finebaum, who hosts a daily college football radio show simulcast on the SEC Network. “This is the embryonic stage of a movement that very well could change this sport for the next generation. It’s going to change everything.

“You look at Mike Gundy for a second. I have no earthly idea how he’s ever going to be able to recruit again, after his 3-4 days of absolute buffoonery. The great debate now is going to exist out there: Who is going to be able to adapt? What coaches are capable of this?”

The Wright family, like hundreds of others across the country with blue-chip sons, is watching.

Ceyair said he won’t be choosing a school where he doesn’t feel confident in the program’s level of social literacy.

“Are you really about the movement or are you just saying it?” Claudius said. “You have to ask yourself: Was it really authentic?”

“Are you really about the movement or are you just saying it? You have to ask yourself: Was it really authentic?”

— — Claudius Wright, father of Loyola High cornerback Ceyair Wright

::

The year 2020 was already set up to be a big one for college athlete rights. The NCAA, because of pressure from name, image and likeness legislation being developed in more than 30 states, was actually preparing to draw up new bylaws of its own to allow players to profit from their time donning school colors — albeit with some “guardrails” that protect amateurism.

When the pandemic hit in March, shutting down spring college sports and football spring practice, it became sufficiently clear that schools were going to be hit where it hurts the most. The revenues lost from the cancellation of the NCAA basketball tournament were one thing. Now imagine if there was no football season.

Most college football players already understood that their games — played in front of tens of thousands and broadcast for hundreds of thousands — created scholarships for water polo teams, erected softball stadiums and made sure Power Five athletic director salaries soared into seven figures.

But the urgency with which conferences and schools began to assemble detailed plans of how they could “safely” return college football players to workouts during the midst of a pandemic? That felt like something new, not just for players but also for longtime observers of the power dynamics.

“I’ve never seen change racing through a sport that has primarily been run by autocratic football coaches who have no real interest or concern about what their players say once they get on campus,” Finebaum said. “Now you’re seeing pockets of resistance at quite a few places. The most important part of it is the pandemic. We’re asking players to do things that, quite frankly, I don’t know if anyone really has their best interest at heart. Right now it’s let’s get college football in stadiums and on your friendly television, and we’ll worry about everything else later.”

“I’ve never seen change racing through a sport that has primarily been run by autocratic football coaches. ... Now you’re seeing pockets of resistance at quite a few places.”

— — Paul Finebaum, college football radio show host

Then, George Floyd happened.

For Claudius Wright’s generation, seeing a Black man die like that, without having even tried to fight back, was painful but not exactly eye-opening.

For Ceyair’s group, it was an awakening, as if the past came to life right before their eyes and became present.

“Everything is just unfolding slowly in front of our eyes,” said Jaylin Smith, a heavily recruited Mission Hills Bishop Alemany cornerback from Palmdale. “We’re finally seeing it all. It’s been happening for over 400 years, now it’s unraveling, seeing how the system is kind of ran, and we have nothing to distract us from it.”

This time, televised Black Lives Matter protests showed more white people in attendance, many of them young and passionate about social justice. Instead of the news focusing on numbers of COVID-19 cases or the potential for a vaccine, channels stayed locked into images of packed streets. Images from marches filled social media feeds in the absence of other events put off by the pandemic.

“Forever, people have always just been able to shut out everything that they don’t agree with,” UCLA offensive lineman Jon Gaines II said. “And this isn’t a time where you can do it.”

Gaines, a rising redshirt sophomore, knows what it feels like to be shut out. When he brought up issues of racism and police brutality previously, his classmates at Milwaukee’s Marquette University High, a private, all-male Jesuit school that has an enrollment that’s 72% white, brushed him off.

Philando Castile, a 32-year-old Black man, was killed by a police officer during a traffic stop in 2016. Gaines, a junior in high school at the time, was outraged that a man, driving with his partner and young daughter in the car, could be gunned down as he complied with an officer’s instructions.

Well, his classmates replied, he had a gun.

His classmates told him he was just being dramatic. That he wanted to make everything about race. He became bitter.

He says he’s done being “gaslighted” now.

Four years later, Gaines realizes he hadn’t been properly educated to stand up for his views. Through African-American history classes at UCLA, he gained confidence in what he believed. This month, he spoke out by leading a video project with UCLA football players and coaches, who took turns reading a pointed script written by Gaines and defensive lineman Odua Isibor highlighting Floyd’s death and systemic racism.

The idea from UCLA’s video came after Gaines’ older brother showed him a video of Ohio State players in a similar project. As more and more players use social media platforms as personal megaphones, it’s creating a “dominoing effect,” Duru said, and the act of questioning authority may expand into matters outside of race.

Athletes at USC, led by track All-American Anna Cockrell, formed the United Black Student-Athlete Association (UBSAA) and released a list of demands this week after consulting with athletic administrators. The group addressed diversity measures like seeking a diverse applicant pool and considering Black candidates for open positions while also lobbying for athletes to be included in conversations about returning to campus amid the pandemic.

Speaking up about any injustices, racial or otherwise, is “our civil, almost humane duty,” said USC offensive lineman Jalen McKenzie, a UBSAA member.

Gaines’ name is listed among the UCLA players who Friday demanded a third-party health official to oversee the football team’s return to training amid the pandemic and protections for players who choose to speak out or to not participate. He is reminded of why he must act now every time he leaves his house to run.

His mother always reminds him to wear his UCLA gear. It could be his shield.

“It could be the thing that saves my life,” Gaines said.

“There is a privilege that comes with being a student-athlete at a Power Five school, yes, but at the end of the day, we’re all still Black men and women.”

::

On June 13, the day of Clemson’s Black Lives Matter protest, WSPA News out of South Carolina posted a video of pickup trucks lined up on a street, letting their Confederate flags fly, one after the next.

Later that day, Clemson’s freshman quarterback, DJ Uiagalelei of Bellflower St. John Bosco, retweeted it with a comment: “Dang this crazy because this where I go to school and I also call my second home … sad to see this.”

Jaylin Davies, a top cornerback recruit out of Santa Ana Mater Dei, was surprised to see it, too. He had visited Clemson with Uiagalelei, rated the top quarterback in the 2020 class, and that wasn’t how he remembered it.

“When we were out there, we didn’t even know that kind of thing happened down there,” Davies said. “They mainly highlighted the campus and the football aspects of Clemson. They didn’t show much of the town and everything.”

On Friday, Davies committed to Oregon.

Beaux Collins is a rising senior at St. John Bosco who was noticed by Clemson coaches as he caught passes from Uiagalelei. Collins committed to Clemson because of the program’s impressive record of turning wide receiver prospects into pros — DeAndre Hopkins, Sammy Watkins, Mike Williams.

The video of the Confederate flags — and the criticism of Swinney’s late-developing response to Black Lives Matter — have not affected his plans to become a Tiger. Even though some in Southern California may not understand it.

“I’d just say it’s a really warm place to be,” Collins said. “You go to eat around town, everybody’s nice and really accepting. It starts with Coach Swinney. He has sent us as recruits and our parents videos of him addressing the issues, and just him being a face of the protest that took place this past week really said a lot to me about him as the head coach.”

Before the pandemic, Bishop Alemany’s Smith had planned a big recruiting trip to the South, where he was considering taking official visits to Texas, Alabama and Clemson, among others.

“It’s going to be tough making a decision about people, what they’re about outside of football,” Smith said. “You want to know about the head coach, what he is outside of football. I’ve been paying very close attention.

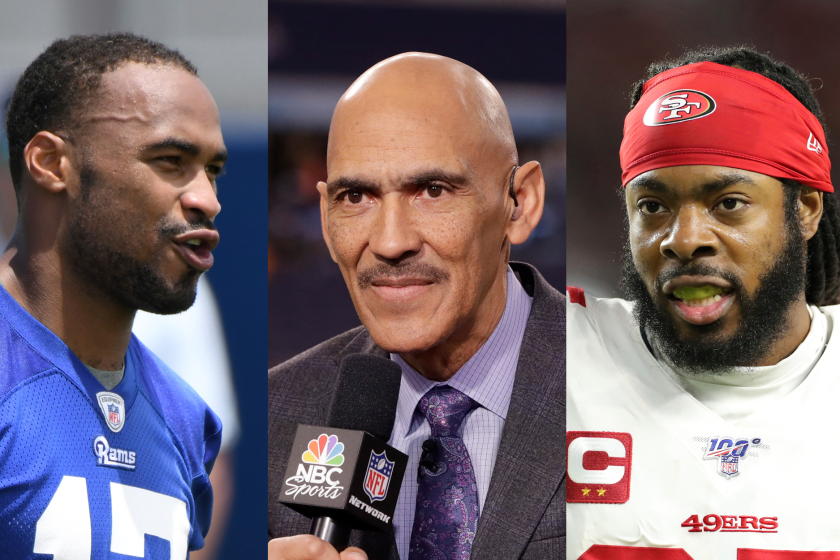

Richard Sherman, Tony Dungy and Robert Woods join The Times’ LZ Granderson and Sam Farmer to discuss social justice, racism and the NFL.

“I feel like before I make a decision, I will want to know about the city more, if it’s a loving city. I think it’s very important to go to a city where you’re loved and that the whole city is safe. That’s a big factor for me.”

Ceyair Wright said that coaches who are recruiting him — Black and white — have been addressing the issue head on, starting with the most basic question: How are you feeling?

“It’s kind of like the elephant in the room right now,” Ceyair said. “It should be addressed. This time is allowing schools to show where they stand on certain issues.”

Ceyair made it known to the world Thursday where he stood. He said the response to his video has been “amazing.”

“I just think that people are extremely pleased with the younger generation,” Ceyair said.

Some of those same fans who had come for his commitment at 8:46 in the morning were left with admiration for the young man and his friends.

“Powerful,” one reply said. “Thank you for using your voices and your platform to share your hearts and experience and to build momentum. There’s a mountain to climb and it’s been there a long time, but we’re moving faster than usual in the right direction. #BLM.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.