Appreciation: Rafer Johnson was a humble champion who put others in the spotlight

- Share via

The most difficult stories to write are those where there is too much to say. Such as, when the subject is Rafer Johnson.

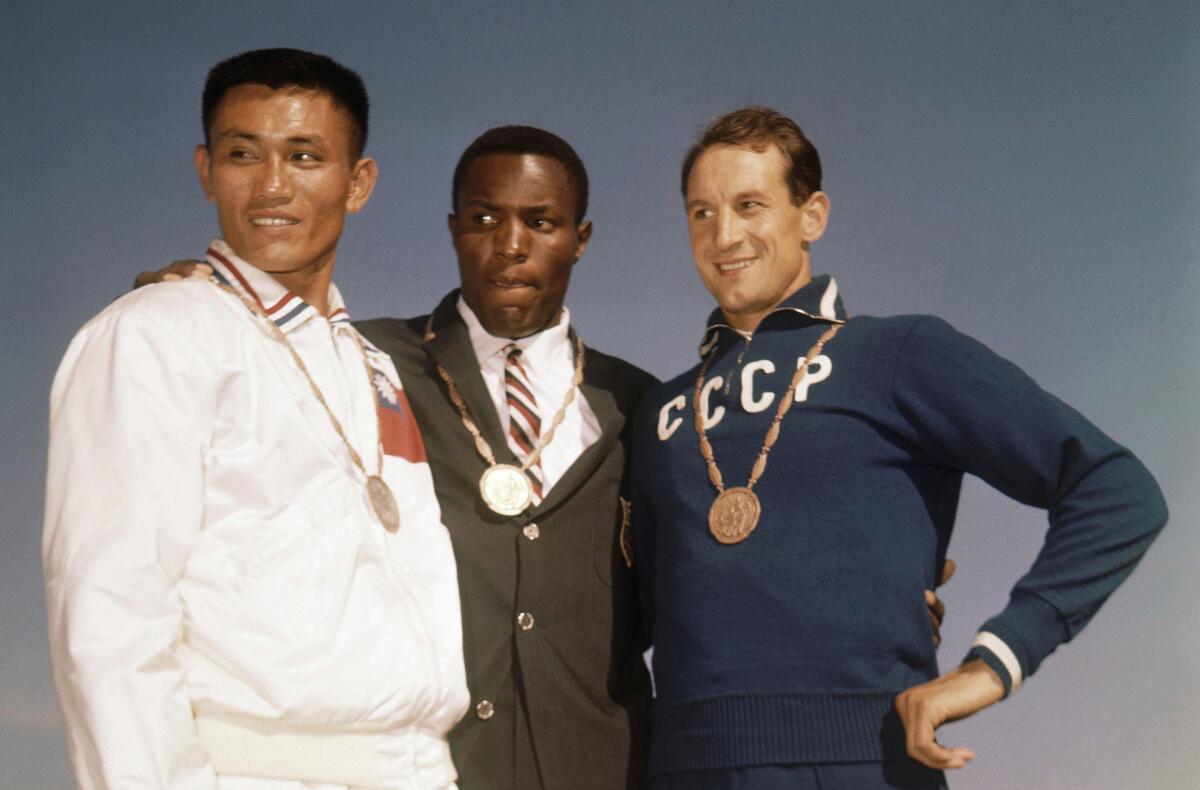

By now you know he died Wednesday. You probably know he was famous because, among so many other things, he won the Olympic gold medal in the 1960 decathlon in Rome. In those days, the man who did that was quickly labeled the world’s greatest athlete, and when you had to run and jump and throw for two days against the world’s best, through increasing exhaustion, on an international stage, the moniker was deserved. These days, that designation seems to lean more toward those who dunk basketballs or throw spirals.

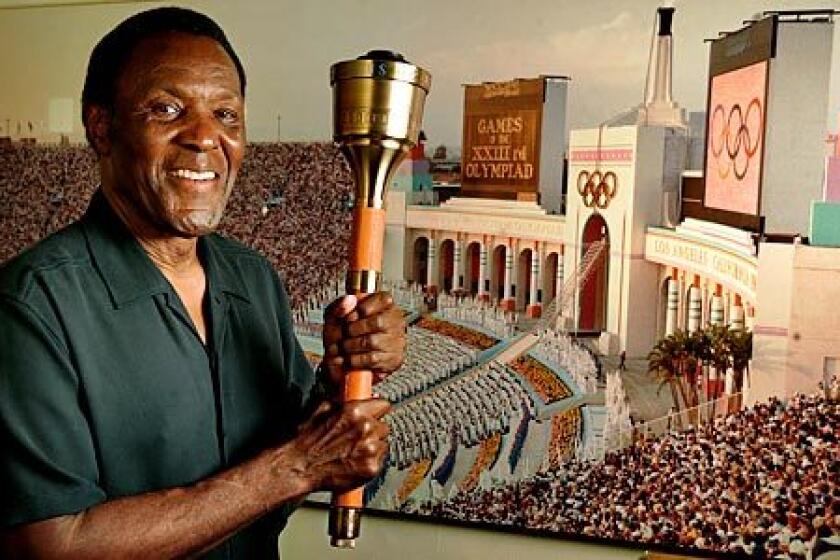

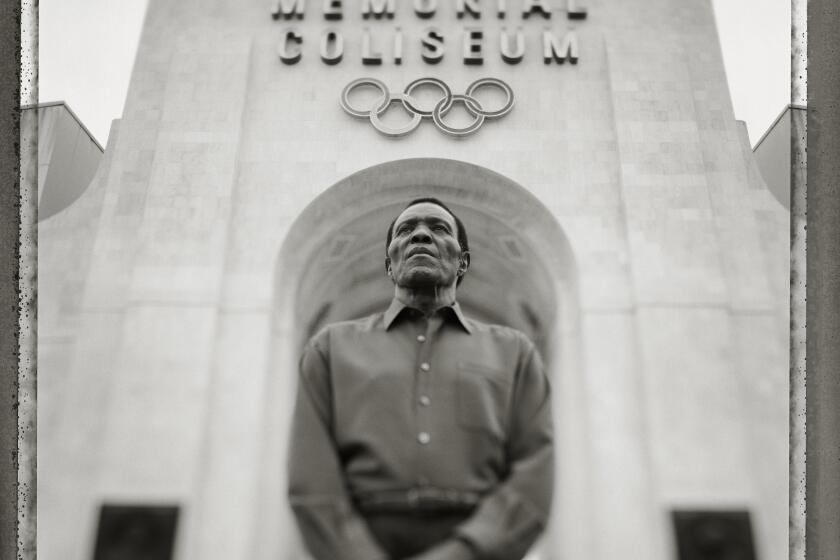

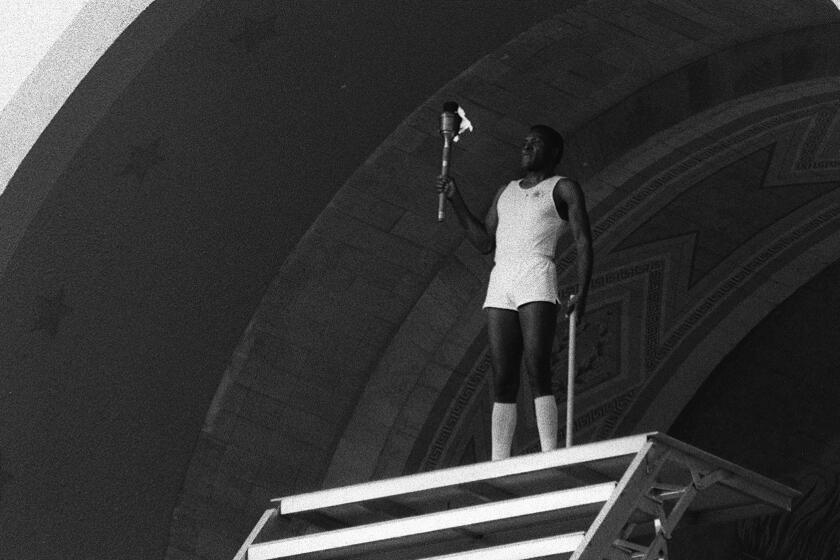

You also probably know his fame extended to lighting the Olympic torch on opening day of the 1984 Games in Los Angeles. His stories of the scary climb on the shaky ladder to get the flame to the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum lighting chute made their way into many of the obituaries.

Same thing with the story of the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy in 1968 in the kitchen area of the old Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. Rafer, an RFK supporter, and Rosey Grier, another muscular athlete, jumped on the shooter, Sirhan Sirhan, pinned him down and wrestled the gun away.

A look back at The Times’ coverage of the life of Rafer Johnson, who died Wednesday at 86.

There is so much more, because he was so much more. The summation of a person’s life is often dominated by awards, plaques on the wall, trophies in the case and placement of the obituary in the local newspaper. His was on the front page of most of them, where it should have been. But not enough of those summations captured what needed most to be said: That Rafer Johnson was the most decent, honest, caring person any of us may ever know.

We were friends about as much as any newspaper person can be friends with a news source. Get too close and your objectivity is gone. We had lunch, did interviews, chatted when we ran into each other about the good old days. My wife and I got to know his wife, Betsy. Years ago, our son participated in the Special Olympics. Rafer was an original founder, cared deeply and asked about that. Our common things led to an exchange of Christmas cards and life information. Had Rafer lived another year, he and Betsy would have celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary.

A life in photos

A goal in one of our interview sessions was to get him to talk about being the deciding vote on the selection committee that put Peter Ueberroth, a little-known travel business executive, in charge of the ’84 Olympics. Rafer’s deciding vote had long been rumored, and it even caused a slight ruffle in the media when Rafer was selected to light the torch. Conspiracy theorists smelled payback, missing the obvious point that Rafer was the best choice, no matter what. I asked about it, even pressed.

“I’d rather not say,” Rafer said that day, and several times after that.

There are certainly people who know, but Ueberroth says he is not one of them.

“I always heard that, but I was never sure,” Ueberroth said Friday. “I do remember that he was one of the first to congratulate me — and to warn me of what was ahead.”

Addressing the voting issue meant Rafer would be injecting himself into Ueberroth’s story. He never injected himself into anybody’s story.

Ann Meyers Drysdale, whose UCLA basketball career brought her into the frequent company of her fellow Bruin superstar, said it well the other day. “With Rafer, it was never about him and always about everyone else.”

There are several unrelated testimonials to Rafer’s selflessness.

When the LA84 Foundation was putting together its recent display, “Rafer Johnson: His Life. His Impact,” Betsy had to secretly scramble for memorabilia stuffed away on garage shelves. Things hanging on walls and on trophy shelves inside his home displayed the achievements of his children, daughter Jenny and son Josh. Things such as gold medals and halls of fame were displayed for dust and cardboard.

The Times’ Bill Plaschke wrote a while back about how stunning it was that Rafer was never awarded a Presidential Medal of Freedom. Go through the list of the hundreds who have — and the dozens of athletes — and you will likely agree.

The 1960 Olympics champion in the decathlon was a regular at UCLA sporting events. “We’ve really lost a legend,” said former athletic director Dan Guerrero.

While Plaschke is correct, it isn’t stunning. Rafer Johnson was among the least self-promoting people to ever live. He loved the spotlight, just as long as it was on somebody else.

Even when dealing with things of great historic value, such as the Robert F. Kennedy assassination, Rafer was reticent. In another of our luncheon interviews, I dug for details of that night. But anything that hinted at heroics, even though his actions were that night, made Rafer uncomfortable. Kennedy had died. That’s all that mattered. He called it one of the “most devastating times” of his life.

The little-known story about the assassin’s gun came out, again after considerable prying, as kind of an afterthought.

“Rosy was wrestling him down and I had my hand on Sirhan’s gun hand,” Rafer said. “It was clenched tight on the gun and I had my hand covering his hand and I held on as tight as I could.”

Eventually, he said, Grier had so much weight on Sirhan that he couldn’t move. That allowed Rafer to slowly pry the gun out of Sirhan’s hand. In shock, he put it in his coat pocket, wandered out to his car and drove home, took his coat off next to the bed and fell into a stunned sleep. A few hours later, he awoke, realized he needed to get back to the hospital, and felt a strange weight in his coat pocket as he put it on.

“I called the police,” he said.

For many others, that would have been a story triggering massive and newfound celebrity — talk show appearances for weeks, maybe even a book. Not for Rafer. He probably saved several more people from getting shot in the melee. He had been a hero, but Rafer’s radar never allowed that blip to surface. When he told the story, he did so only succinctly, and only when pressed.

Before writing about a former athletic star, I usually check the various compilations of Jim Murray columns. The characterizations of the late, great Times Pulitzer Prize winner were always classics and worthy of repeating. I looked long and hard. There was very little Murray on Rafer. That’s not a discredit to either. Murray’s best columns usually dealt with some measure of flamboyancy. Rafer had little. He was self-effacing, almost to a fault. In today’s me-first world, he would disappear, as he kind of did.

When Rafer ran the grueling 1960 decathlon final race, the 1,500 meters that he hated the most, he did so by staying close enough to his friend and UCLA teammate, C.K. Yang, to manage enough points for the gold medal. Afterward, he didn’t grab an American flag and circle the arena. He went to Yang, put his arm around him and leaned on him, in exhaustion, friendship and commiseration.

Before Rafer pounced on Sirhan, he made sure that Kennedy’s wife, Ethel, walking with him about 20 feet behind, was safe. He got her down to the ground and protected, then charged the shooter.

Ethel Kennedy has a Presidential Medal of Freedom.

When Rafer was UCLA’s student body president, he signed the paychecks of coaches, including John Wooden. “When somebody asks me about that,” Rafer said years later, “I always feel embarrassed.”

John Wooden has a Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Ueberroth’s recent words best summarize what so many of us feel now.

“We’ve lost a marvelous human being, and I’ve lost a true friend,” he said. “With deaths these days, for some of us older than 80, we take these things in stride. With Rafer, I’m having trouble doing that.”

Presidential Medals of Freedom are, occasionally, awarded posthumously.

Rafer Johnson’s legacy was interwoven with Los Angeles’ history, beginning with his performances as a world-class athlete at UCLA.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.