Column: Hideki Matsuyama’s historic Masters win carries different weight in Japan

- Share via

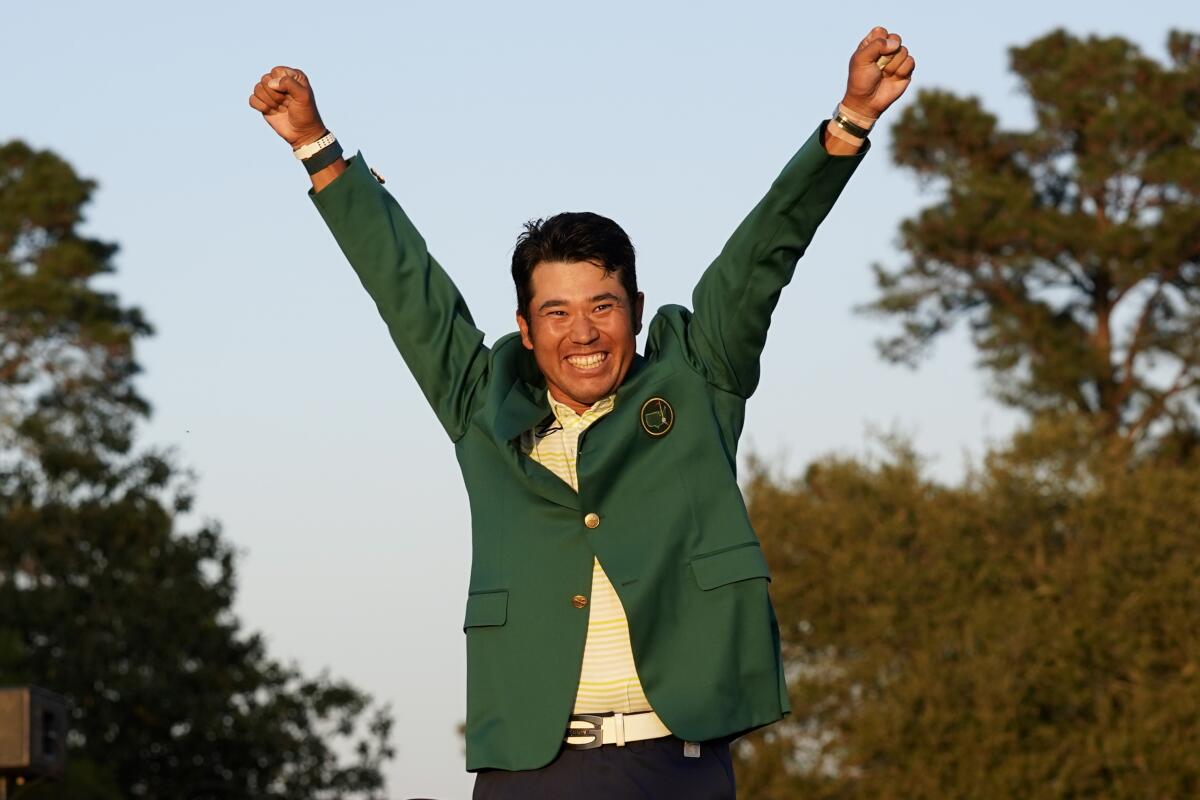

Hideki Matsuyama looked as if he was fighting back tears.

He scrunched his face. He looked down. He blinked.

The question from the Japanese talk show host that elicited the involuntary physical response wasn’t about his victory at the Masters earlier Sunday, but about his first time playing in the tournament.

“I think I was able to change when I was allowed to come here 10 years ago,” Matsuyama said in Japanese during a remote interview with the Tokyo Broadcasting System program “Hiruobi.”

“I’m glad I’m able to deliver positive news to the people who pushed me forward then. Thank you.”

His face still red, Matsuyama bowed to the camera.

The first time Matsuyama was invited to the Masters, he almost didn’t show up. At the time, he was a 19-year-old collegiate student-athlete in the Tohoku region, which a month earlier had been devastated by a 9.0-magnitude earthquake and a related tsunami that killed more than 20,000 people.

Matsuyama, who earned a Masters berth by winning the Asia-Pacific Amateur Championship, was in a training camp in Australia when the earthquake and tsunami ravaged the region. When he returned to Tohoku Fukushi University, he experienced the effects of the destruction firsthand, losing weight as he survived on a diet of instant ramen.

“You didn’t know whether it was appropriate to leave,” Tohoku Fukushi golf coach Yasuhiko Abe said on “Hiruobi.”

The Olympic volunteers in the red and gray tracksuits walked down to a section of seats in the lower half of Gangneung Ice Arena and asked the reporters there to relocate to the upper deck.

As Matsuyama debated whether to play in the Masters, he started receiving letters and faxes from people in the Tohoku region who encouraged him to accept the invitation. Matsuyama listened to them, taking with him the more than 200 pieces of correspondence, which he read throughout the tournament.

Matsuyama became the first Japanese golfer to earn low-amateur honors at the Masters, finishing in a tie for 27th overall with the previous year’s Masters champion, Phil Mickelson. A decade later, on Sunday, he became the first Japanese golfer to be crowned Masters champion.

How Hideki Matsuyama won the 2021 Masters.

He’s also become a symbol of the Tohoku region’s recovery, alongside figure skater Yuzuru Hanyu and baseball player Rouki Sasaki.

Hanyu was practicing at his home rink in the Sendai prefecture when the earthquake struck. He ran into the streets in his skates and was forced to spend three days in an emergency shelter. He later became a two-time Olympic gold medalist.

Sasaki, who is from the Iwate coast, lost his father and a set of grandparents in the tsunami. Instead of accepting an invitation to play for a baseball powerhouse, Sasaki attended high school in the same town in which he and his family rebuilt their lives. While there, he threw a 101-mph fastball that made him the country’s most sought-after pitching prospect since Shohei Ohtani. Sasaki, now 19, plays for the Chiba Lotte Marines.

Rouki Sasaki, a small-town 17-year-old high school senior, has a triple-digit fastball. He overcame a family tragedy and is considered the next Shohei Ohtani.

While Matsuyama’s triumph was a first for Japan, it wasn’t the same caliber of breakthrough as, say, Hideo Nomo’s debut with the Dodgers. Since Nomo moved to the United States in 1995, Japanese athletes have become gradually more competitive on the world stage. They don’t think nationally, as athletes from previous generations did. They think globally, as was the case with Matsuyama, who dreamed of playing in the Masters after watching Tiger Woods win the 1997 tournament.

Japan regularly exports players to Major League Baseball and to European soccer leagues. It has won two World Baseball Classics and a Women’s World Cup. Naomi Osaka is a four-time Grand Slam champion. Naoya Inoue is considered one of the world’s top boxers. And in the last four years, two of its sprinters have broken the previously impenetrable 10-second barrier.

Matsuyama’s achievement was a step toward greater distinction in more popular sports — for example, of Ohtani becoming as dominant a two-way player for the Angels as he was for the Nippon-Ham Fighters, or of teenage prodigy Takefusa Kubo leading the men’s national soccer team to World Cup glory.

Manager Joe Maddon is keeping things simple in the Angels’ two-way experiment with Shohei Ohtani, an approach that could be a good fit for the standout.

Nonetheless, in a country that obsesses over one thing before quickly moving on to the next, Matsuyama is enjoying his time as the man of the moment. During the weekend, Japan was fixated on swimmer Rikako Ikee, a 20-year-old leukemia survivor who won four events at the Olympic trials. Now, it’s Matsuyama’s turn, just as it was once Inoue’s or Rui Hachimura’s or the national rugby team’s.

However society at large comes to view his achievements, Matsuyama’s place in Japanese golf history is secure. In a country that celebrates regional differences, so is his place in Tohoku mythology.

The main page on Tohoku Fukushi University’s website includes four rotating graphics. One of them is of Matsuyama.

“Graduates are challenging the world with the heart of welfare,” it reads in English.

Every shot from Hideki Matsuyama’s final round at the Masters on Sunday.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.