Before Jackie Robinson, Jorge Pasquel broke baseball’s color barrier — in Mexico

- Share via

VERACRUZ, Mexico — Pedro “Charrascas” Ramírez was born more than a century ago and he concedes his eyesight is fading and his knees ache when he climbs the narrow 15-step staircase to his breezy second-story apartment in the old part of Veracruz.

His mind, however, remains sharp and the memories it holds may prove key to an implausible campaign to get a flamboyant, daring Mexican millionaire named Jorge Pasquel enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Ramírez is the lone survivor of the 1946 Mexican League season, one in which Pasquel, the league president, used suitcases full of money to lure nearly two dozen white American players south, where they played alongside Negro League stars banned from the majors because of the color of their skin.

Pasquel’s gambit was not sustainable, and the league would later go bankrupt. But it became the first in professional baseball to fully integrate.

Although Jackie Robinson would join the Brooklyn Dodgers a year later in 1947, the last vestiges of the color line would not disappear until 1959, when Pumpsie Green debuted with the Boston Red Sox, the last major league club to integrate.

Pasquel was gone by then, having died in a 1955 plane crash at age 47. But now a grandson he never knew is revisiting his accomplishments and insisting that Pasquel’s role in integrating baseball makes him worthy of enshrinement in the Hall of Fame.

“He belongs for many reasons,” said Miguel Pasquel, a sports broadcaster in Mexico City. “He really helped a lot to break the color barrier. Thanks to him many, many Negro League players were able to play in Major League Baseball, including more than 18 Hall of Famers who were here in Mexico.

“This is not a dream. This is justice which my family and myself are looking for.”

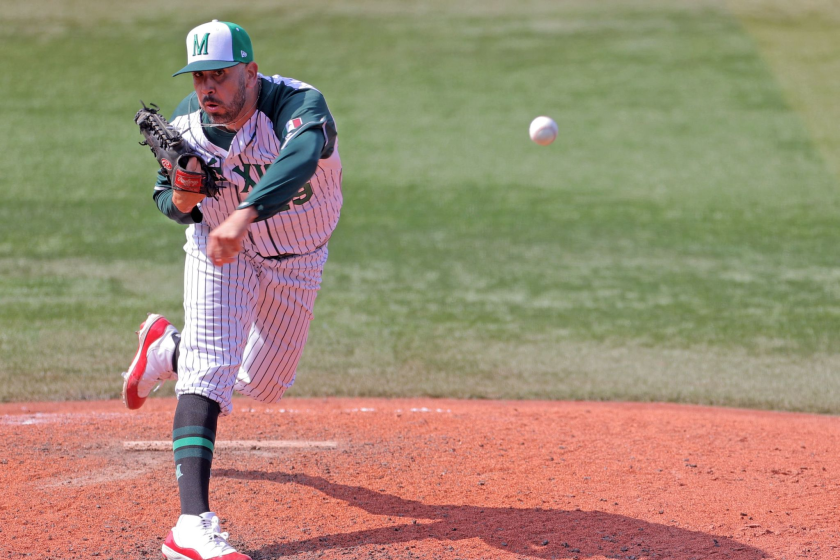

Miguel’s cousin Bernardo Pasquel, owner of the Mexican League team in Veracruz and the only member of the family still involved in baseball, said current events have made Jorge Pasquel’s story important again.

“Everything that’s going on right now, Black Lives Matter and all the social injustices, it’s a relevant story,” he said. “There was this guy that, 70 years ago, brought athletes to Mexico, treated them like the stars that they were no matter the color of their skin. That’s what is relevant about this.”

Josh Rawitch, president of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, N.Y., doesn’t disagree. But the bar Pasquel must clear is a high one.

Because he was a non-player who made contributions to the game before 1980, Pasquel must be considered alongside hundreds of nominations for umpires, executives and managers of the so-called Classic Era. Those nominations are whittled down to eight candidates who are voted on by a panel of 16 Hall of Fame members, club executives and baseball historians, with 12 votes needed for induction. The next Classic Era ballot won’t be considered until December 2024.

Rawitch noted that when you are competing against the most iconic figures from the first century of baseball’s history, the odds of making it onto the ballot, much less into the Hall, are long ones — especially since Pasquel’s story isn’t widely known.

Reflecting on the 100th anniversary of immensely popular Negro League baseball is particularly instructive during this time of racial reckoning.

The impact of what he accomplished, however, still resonates, although Ramírez is one of the few people still alive who experienced Pasquel’s showmanship and visionary thinking first-hand.

Nearly a decade before Robinson’s big-league debut, Pasquel integrated the Mexican League by recruiting top Black players, eventually signing more than 200 by giving them cars, apartments, dignity and contracts that had zeros where their old ones had decimal points.

Ramírez never saw that kind of money. Few Mexicans were paid anything close to what the Negro League players and white major leaguers got. But few complained. The U.S. players not only brought the Mexican League attention, but made the league better.

“Do you know how much I earned? Two-hundred-fifty pesos a month, said Ramírez, who hit .297 and won 51 games on the mound in 13 seasons in Mexico, according to the Mexican baseball encyclopedia. “I imagine that those people who came earned a fortune. Good players continued to come. There was always good baseball.”

That was just the first step of Pasquel’s plan to integrate the game he loved. During a frenzied two-year period beginning in 1946, Pasquel and his brothers tried to lure top white players such as Hank Greenberg, Hal Newhouser and Bob Feller — three future Hall of Famers — by offering a $1 million combined at a time when the top salary in professional baseball was $55,000.

Pasquel dropped another $25,000 in cash on the bed in Stan Musial’s hotel room in an effort to entice the National League batting champion south.

None of those players accepted, but 21 others did. Pitcher Sal Maglie and outfielder Danny Gardella were two of eight players who left the New York Giants. Left-hander Max Lanier walked away from the St. Louis Cardinals in mid-season. So did infielder Lou Klein and pitcher Fred Martin.

In Mexico the pitchers threw to Black catchers, the infielders turned double plays with Black infielders, they showered and dressed next to Black teammates and they took orders from Black managers. The games they played in were, in many ways, just as good as the baseball in the U.S.

Without the success — and the threat — of Pasquel’s experiment in Mexico, would Happy Chandler, the commissioner of baseball in the U.S., have overruled 15 team owners and allowed Robinson to join the Dodgers in 1947?

“I don’t think he would have,” said Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Mo., who participated in a recent panel discussion on Pasquel at Harvard. “I don’t know that you can have one without the other. But what I will say with no uncertainty is that [Pasquel] played a tremendous role helping set the stage for that monumental moment.”

A role big enough that he should have a plaque in Cooperstown, Kendrick said. “Why his name has never surfaced in any real, meaningful way is beyond me,” he said. “Most fans just didn’t know him.”

“Racism was not present here. There were no problems.”

— Ramirez, Mexican League baseball in the 1940s.

Ramírez did.

“He was eccentric,” the old ballplayer said with a chuckle.

At one time Pasquel owned six Lincolns and had a haberdashery in his massive Mexico City mansion, often inviting players in to pick through his walk-in closets and take home whatever fit.

“Once I went to his house and he told me to grab some shoes. Florsheim shoes,” Ramírez said. “I sold them for 100 pesos.”

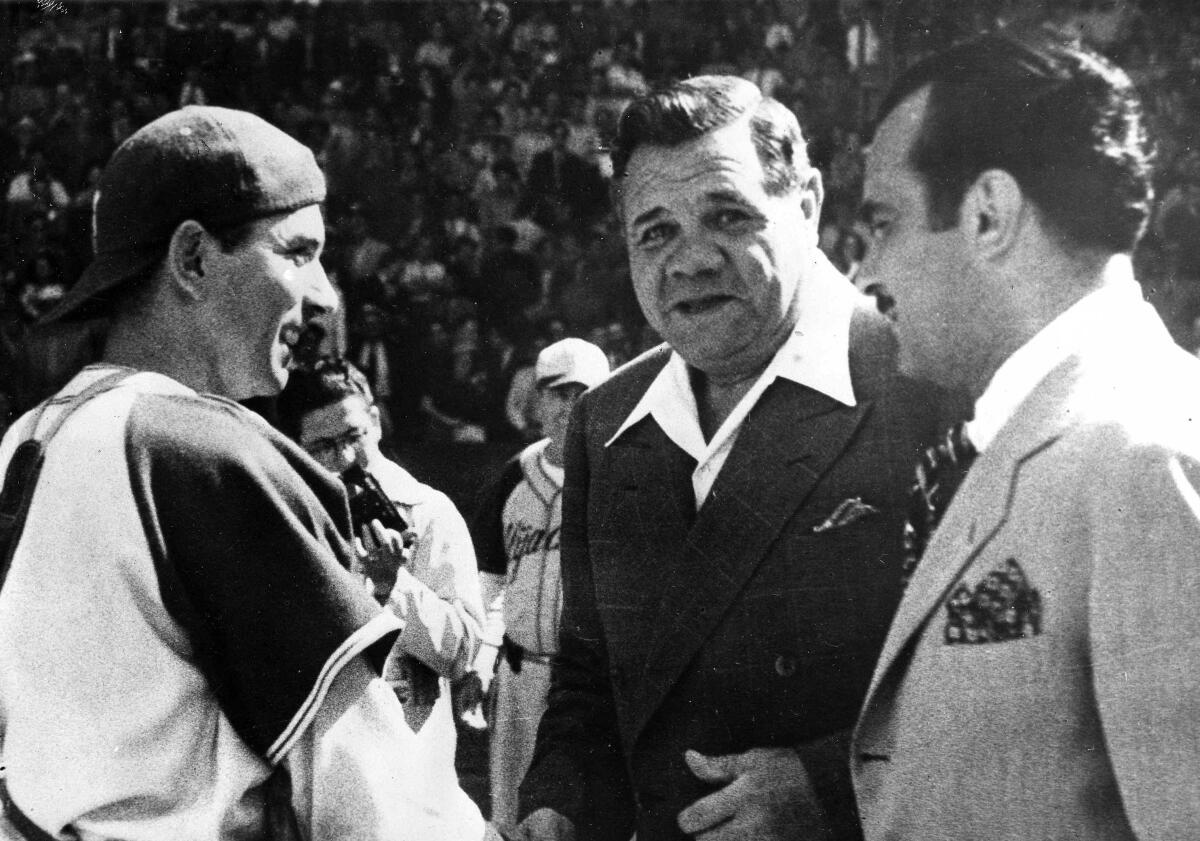

A natty dresser, Pasquel attended games wearing a suit — often with a pearl-handled pistol tucked in the waistband — but that didn’t stop him from borrowing a catcher’s mitt and warming up pitchers. One season, disappointed with his team’s performance, he traded the suit for a uniform, managing Veracruz to a league championship.

Another time Ramírez showed up at the ballpark in Puebla only to find fans crowding outside the gates. When Pasquel asked why, they said the owner of the land where the ballpark stood had locked them out.

“A half an hour later I returned,” Ramírez said. “[Pasquel] had bought the land.”

Pasquel was a soft touch who made huge donations to charity and would open his wallet when asked for help. But he also had a temper, once killing a man in an Old West-style gunfight in the streets of Nuevo Laredo.

“He was a rock star during his age,” said Bernardo Pasquel, the baseball team owner.

His brothers, who all sported identical thin, short mustaches, helped run the varied businesses that supported Pasquel’s baseball ambitions. His brother Bernardo — for whom the younger Bernardo was named — also was eccentric, keeping a lion named Elsa at his house in Mexico City.

But Pasquel, who never smoked or drank, also had rules.

“If you came up to him smoking or with alcohol on your breath, he said ‘No, no, no. If you want to talk to me, no cigarettes or alcohol breath,’” said Ramírez who, like Pasquel, is enshrined in the Mexican baseball hall of fame in Monterrey.

The main thing Pasquel didn’t tolerate was racism. He was born and raised in Veracruz, which, as Mexico’s most important port, has long been the main point of entry for people from Cuba and the Caribbean, as well as slaves from Africa. Many of those people settled along the Gulf coast, infusing the culture with Cuban and African influences and making the state one of the most ethnically diverse in Mexico.

“Racism was not present here,” Ramírez said from the sofa of a living room packed with memorabilia from his playing days. “There were no problems.”

That wasn’t true across the border. When Pasquel and his chauffeur once stepped into a diner in Texas, the manager showed the light-skinned Pasquel to a table but insisted the driver, who was much darker, wait outside.

“It was the first time in my life that I felt free. We could go anywhere we wanted, eat anywhere we wanted, do anything we wanted and not have to worry about anything. We just had a wonderful time and I owe that experience to Jorge Pasquel.”

— Monte Irvin, Black baseball player who competed in the Mexican League

That incident would later fuel Pasquel’s passion to have a baseball league in which a man’s talent, not skin color, determined whether he could play.

Unlike playing in exhibition games, “the Mexican League meant that you see each other as equals,” said Adrian Burgos Jr., a history professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and author of “Playing America’s Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line.”

“You’re teammates, you are sharing the locker room, the dugout space. It is a very different dimension. And that’s what Pasquel tapped into.”

Off the field too. Even when Blacks began integrating the major leagues, they often were barred from the hotels and restaurants their white teammates used. In Mexico City, Pasquel gave his players luxury apartments and when they went on the road, there were no signs telling them which drinking fountains or restrooms to use.

“It was the first time in my life that I felt free,” the late Monte Irvin, who would later play in the majors with the Giants and Chicago Cubs, repeatedly told interviewers, among them author Peter Golenbock. “We could go anywhere we wanted, eat anywhere we wanted, do anything we wanted and not have to worry about anything. We just had a wonderful time and I owe that experience to Jorge Pasquel.”

Among the Negro League stars Pasquel signed were future Hall of Famers Cool Papa Bell, Josh Gibson, Ray Dandridge, Martín Dihigo and Willie Wells.

“Here in Mexico, I am a man,” Wells told Pittsburgh Courier sportswriter Wendell Smith. “I can go as far in baseball as I am capable of going.”

Some, like Dandridge, learned Spanish. Another, outfielder “Wild Bill” Wright, never came back to the U.S., retiring as a player and spending the last 40 years of his life in the town of Aguascalientes, where he owned a restaurant.

“I can’t recall any arguments down there about race or anything,” said poet and journalist Quincy Troupe, whose father, also Quincy, played eight seasons in Mexico. Troupe, like the children of many Black players in Mexico, grew up speaking Spanish after being tended to by nannies provided by Pasquel.

By the mid-1940s, with the Mexican League full of Black players, Pasquel began recruiting Latin American players, such as Tomás de la Cruz, Roberto Ortiz, Chico Hernández and Antonio Ordeñana, who had been fringe major leaguers. But by 1946 he was all in, offering exorbitant contracts not only to Greenberg, Musial and Feller but also to Ted Williams, Vern Stephens, Phil Rizzuto and Joe DiMaggio.

Most of Pasquel’s overtures were unsuccessful, but major league owners felt Pasquel’s boldness had to be answered, so Chandler, the baseball commissioner, instituted a five-year ban for any player who jumped to Mexico.

Pasquel responded by offering Chandler $50,000 to become commissioner of the Mexican League.

“[Pasquel] was a direct challenge to a number of the ideas that were the supporting rationale for the segregation of MLB,” Burgos said. “One of them was that white players were unwilling to play with Black players. As Danny Gardella and a few others began signing and migrating south, that disrupted that narrative. The other was he showed players would be invested in breaking the color line and breaking down racial segregation if the price was right.

Slowly, more and more Mexican players are reaching the highest levels of baseball, a feat reflected in Mexico’s Olympic debut.

“Owners didn’t want to pay these players more than they had to. They were trying to exercise a monopoly on talent. That is what raised the ire of owners.”

Baseball also was operating under the reserve clause, which bound a player to his current team indefinitely. Players breaking their contracts to accept more money in Mexico not only threatened the sport’s segregation, but also its financial model by creating the option of playing elsewhere.

In response to Pasquel’s raids, major league salaries spiked overnight. Musial’s went from $13,500 in 1946 to $31,000 a year later. Greenberg, already the best-paid player in the game, got a $30,000 raise, while Newhouser, another player Pasquel had enticed, nearly doubled his salary to $70,000.

But the biggest threat resulting from Pasquel’s hiring was a lawsuit filed by Gardella to overturn Chandler’s five-year ban on players who jumped to Mexico. When a federal court ordered a jury trial to investigate baseball’s labor practices, the owners quickly realized the reserve clause likely would be overturned, potentially costing them millions in salary. So they offered Gardella a lucrative settlement and a chance to return to the major leagues.

It would be 26 years before an arbitrator finally ruled against the owners in another lawsuit, brought by pitchers Dave McNally and Andy Messersmith, that ushered in free agency and changed the landscape of professional sports forever.

“Who knows what happens if Danny Gardella doesn’t settle the lawsuit?” Dodgers historian Mark Langill said. “Why would [the owners] settle it unless they were nervous he might win?”

The threat Pasquel posed to the major leagues was short-lived — the money he spent to import American players bankrupted the Mexican League after two seasons and by 1952, Pasquel and his brother Bernardo were out of baseball. Even so, his influence still is being felt today. Pasquel may not have ended segregation or overturned the reserve clause, but he certainly hastened the demise of both.

And while he was seen as a villain by U.S. baseball, he was a hero in Veracruz, where more than 20,000 mourners lined the streets the day his coffin was carried through the old part of town.

But is that enough to get him in the Hall of Fame nearly seven decades after he died?

“The time is right whenever we can figure out an opportunity to right a wrong,” Kendrick said.

For Burgos, the question is one of time, not timing.

“One of the dimensions that becomes challenging is the longevity,” he said. “Was Pasquel around long enough to be enshrined in Cooperstown?”

Ramírez, who at 101 has been around longer than most, said longevity can be overrated. In Pasquel’s case, he said, it’s what he did, not how long it took him to do it, that counts.

“Should he be in the Hall of Fame?” Ramirez asked, repeating the question. “¡Si! Because he didn’t discriminate.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.