How did it become legal to be so pushy in the NFL?

- Share via

There’s nothing subtle about the shove.

One of the plays the Philadelphia Eagles run in short-yardage situations is a sneak with a pair of players immediately behind the quarterback, each poised to push on his backside as soon as the ball is snapped.

It’s the “double-cheek push,” or at least that’s how NBC’s Cris Collinsworth described it a few weeks ago, and it’s emblematic of what we’re seeing all over the NFL this season. Instead of traditional blocking schemes, these surging clusters of humanity turn the ball carrier into a cork bobbing in a wave.

“It’s one of those ways, if you’re trying to get a yard, it seems like a pretty efficient way to be able to do it,” said Rams coach Sean McVay, whose team plays the Chargers on Sunday. “And maybe you’ll see it this week if we get into those short-yardage situations.”

Remember the “Bush Push”? That was 17 years ago when USC running back Reggie Bush used all his might to help knock quarterback Matt Leinart into the end zone for the winning touchdown at Notre Dame. It was a controversial moment because aiding the runner in that way wasn’t allowed in college football at the time. Compared to what’s happening in the NFL, that shove in South Bend was merely a gentle nudge.

Sports Info Solutions recently looked specifically at quarterback sneaks and calculated through the first 12 weeks that Philadelphia led the league in that department by a wide margin. Heading into December, the Eagles had executed 24 sneaks and 21 of them resulted in first downs. The next-closest teams were Cleveland (15 of 18), San Francisco (11 of 13), Cincinnati (11 of 11) and Chicago (eight of nine).

Former NFL and UCLA running back Maurice Jones-Drew said it often boils down to a simple calculation: Which 11 players are stronger?

The Times’ Sam Farmer analyzes each matchup and predicts the winners in NFL Week 17. The Bengals will edge the Bills while the Chargers will beat the Rams.

“It’s just a mindset that you have that you’re going to fight for every inch,” Jones-Drew said. “I remember defenders saying, ‘Hey, we’re going to start taking your legs out because we don’t want to hold you up and then these other 300-pounders come in and knock us out.’

“You’ve got to remember, when you get the football it’s 11 on one. There’s 11 guys trying to tackle you. So how do you even those odds out? Other guys are going to help you with that rugby scrum.”

For decades, NFL rules prohibited offensive players from directly aiding a runner in any way, whether it was pushing or pulling him. But in 2005 — six months before the Bush Push — the league clarified its stance. There would be no pulling of ball carriers by teammates, but pushing was too difficult to legislate.

“What the league found was so difficult was you never were sure who was pushing who,” said Mike Pereira, the former NFL director of officials who became the rules analyst for Fox. “So you’re not necessarily pushing the runner. You could be pushing someone else that’s in contact with the runner. So it became really too difficult to officiate. Therefore, we just said, ‘OK, it’s legal to push.’ ”

The difference now is that teams are beginning to incorporate push plays into their repertoire.

“There’s a certain thing [about] pushing guys across the edge,” said Rams quarterback Baker Mayfield, more pushee than pusher. “You talk about it after the game and you see the momentum. You see the offensive linemen getting involved and you see the passion in guys and the will and the want to win.”

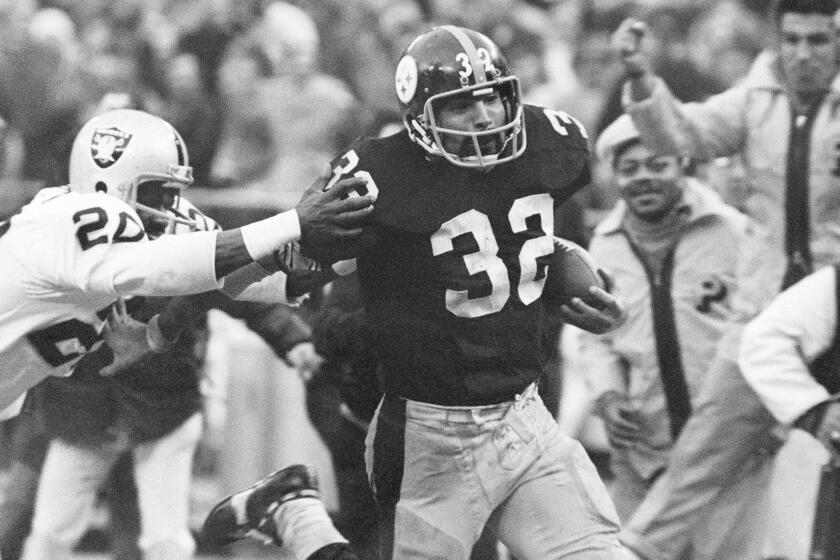

Dec. 23 will mark the 50th anniversary of the ‘Immaculate Reception,’ Franco Harris’ famous catch in 1972 that changed the course of Steelers football.

From the perspective of an offensive lineman, turning a one-yard gain into a five-yard pickup is an opportunity to set the tone in a game.

“I think it’s huge,” said retired All-Pro tackle Andrew Whitworth, now an Amazon Prime Video analyst. “It’s a symbolizing play of the day, kind of the mentality of your O-line. I always look, when I’m watching the line play in a game, for one of those type plays early in a game. When you see those guys fly in to push a pile, you can kind of tell where their head is for the day.”

Not everyone sees the now-routine occurrence of moving mosh pits as a positive.

“You could say that these scrums have become a safety issue,” Pereira said. “When you have all those bodies and all those legs moving forward … it does seem to be a player-safety type thing.”

There is a belief within the league that these types of push plays will be under scrutiny in the spring when teams propose and vote on potential rule changes.

As for the Eagles, they mix it up every so often. Sometimes, when everyone is squeezing down in the middle, they will pop the ball outside to the perimeter and get yards that way.

Sneaky, sneaky.

Times staff writer Gary Klein contributed to this report.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.