- Share via

Myles Johnson folded his 6-foot-10 frame into his restaurant seat for a lunchtime repast of salmon rolls, shrimp tempura and other Japanese delicacies, never imagining the menu would also feature a challenge from his mother:

What are you going to leave your children, what is going to be your legacy?

In many ways, it was an odd question. Johnson was only 21. He was both a budding college basketball star and an emerging presence in the world of engineering, a year away from graduating magna cum laude from Rutgers University as part of a journey that would lead him to UCLA graduate school this fall.

What is going to be your legacy? Johnson wasn’t even sure what he was going to have for dinner.

Gigi Johnson had intended her query as a way of stimulating more than small talk at the restaurant near their Long Beach home. She knew that basketball players who went on to the NBA usually gave back to their communities and told her son to pick a passion project, something he could sustain.

There were certainly things he wanted to change. In his college classes involving the STEM fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics, Johnson watched the number of Black classmates dwindle to a handful as he moved into more advanced coursework. He didn’t have a single Black professor in any STEM classes.

His mother’s question surprised him. An answer didn’t immediately come to mind. He said he would have to think about it, his big idea forming in the hours to come.

It didn’t take much effort, really. Giving back was a family tradition.

::

Engineering is practically a Johnson birthright.

Rick Johnson is an electrical supervisor with the Los Angeles Unified School District and his sister, Camille Lewis, holds a master’s degree in electrical engineering from Georgia Tech. Gigi Johnson had taken engineering classes at Long Beach State before veering into criminal justice and a job with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security in Customs and Border Protection.

“People can never wrap their heads around a person loving more than just basketball.”

— Rick Johnson, father of UCLA center Myles Johnson

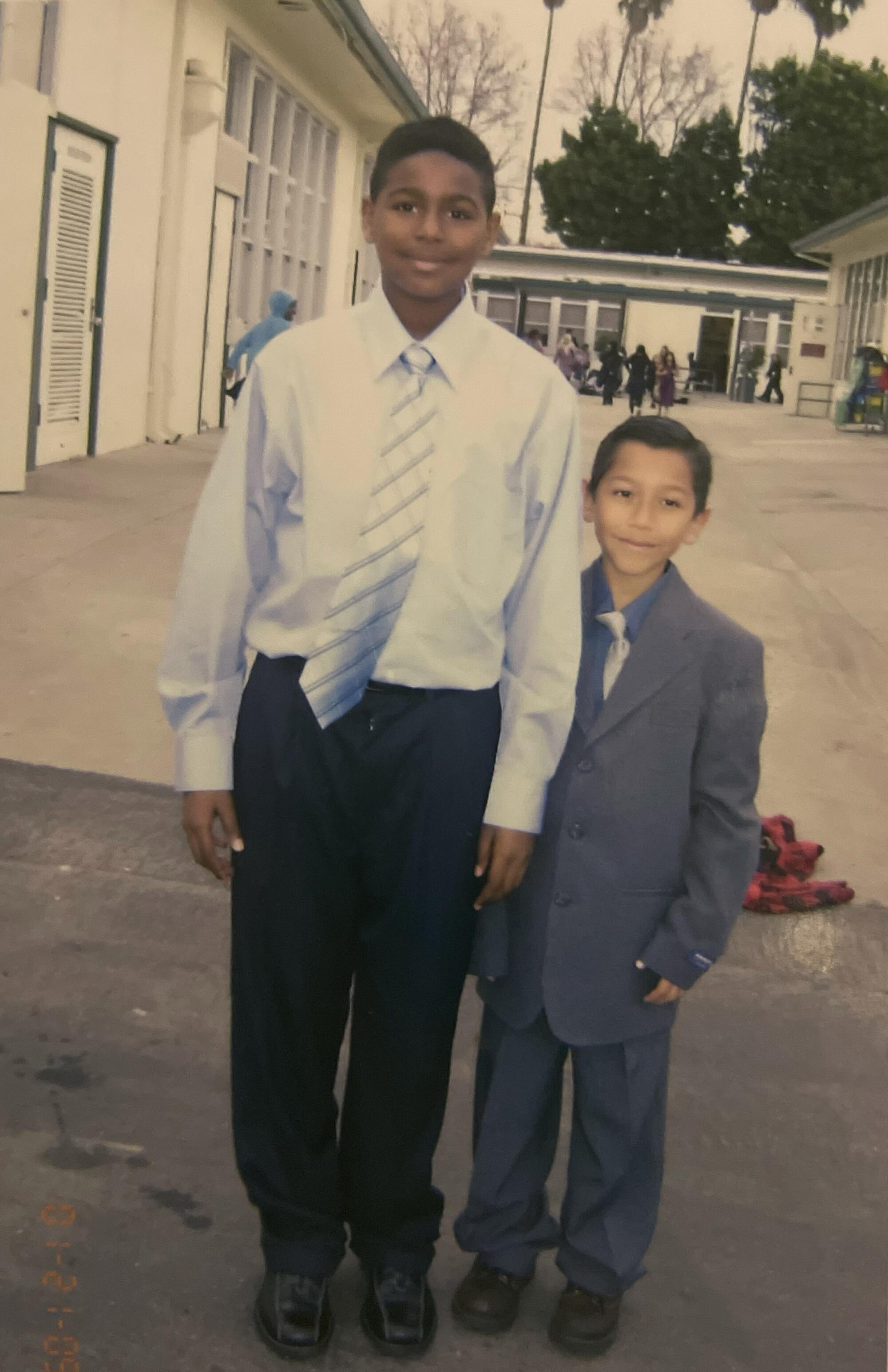

The genetic cocktail seemed to infuse Johnson with a natural curiosity. As a boy, he preferred Legos over action figures because they were more interactive and enjoyed dismantling and reassembling old laptops.

Even weekends centered on tinkering. Not wanting their only son sitting around the house watching cartoons, the Johnsons enrolled him in a weekly activity fair called Saturday Science at King/Drew High in Los Angeles.

“The program starts in kinder,” Rick Johnson said, “but Myles got in a year before because I kept going up to the place bugging them until finally the lady just said, ‘We’ll let your son in.’ ”

The head start paid quick dividends. Johnson understood fractions before his peers, taking second-grade math while in the first grade. For a science fair project, he showed how an electric current could turn a dill pickle into a lightbulb.

By the time he reached middle school, he was taking math at Mayfair High School in Lakewood.

It wasn’t all math and science. He studied Japanese in high school, reaching conversational level, and developed a love of cooking, especially chicken dishes. He cultivated an early interest in philanthropy, handing out boxes of grilled chicken on Los Angeles’ skid row and later traveling to Puerto Rico to distribute sneakers to needy children.

There was also that other hobby that involved dribbling and shooting. But as he progressed from youth basketball to his high school team at Long Beach Poly to the brink of college, his proficiency in engineering was seen as a hindrance by coaches who wanted him to focus on their preferred pursuit.

“People can never wrap their heads around a person loving more than just basketball,” Rick Johnson said. “We’ve sat down with so many coaches — oh, my God — even when he was going through recruiting and the first thing that comes out of their mouth is, ‘Well, he doesn’t love basketball.’

“And we’re like, ‘No, he loves basketball, it’s just that he loves other things too.’ ”

UCLA and USC the Pac-12 amass its best across-the-board showing in NCAA tournament history, piling up 13 victories. Now they’re hungry for more wins.

Those dual passions required some juggling. At Rutgers, the basketball team set its practice schedule around his engineering classes. Double reminders on his phone let him know where he needed to be, one notifying him two hours before something and another 30 minutes ahead.

“If it’s a super-busy day,” he said, “I’ll allot time to actually eat.”

::

His smarts made him the head of the class.

His height put him literally a head above everyone else.

Johnson towered over his classmates and even some teachers, always measuring off the charts.

There was no easy explanation for this blossoming beanstalk. His father is 6 feet 4 and his mother 5 feet 7. Neither had more than dabbled in sports.

“We have no one that’s tall in our family line, no true athlete to that extent,” Gigi Johnson said. “So I claim it’s G-o-d all day.”

Interest among college suitors dissipated after Johnson suffered a broken kneecap before his junior season at Poly. Upon his return a year later, he picked Rutgers because of its combination of engineering excellence and a basketball team that competed in the powerful Big Ten Conference.

He was known as “Myles the Monster” in a nod to his size, even though the nickname didn’t really fit someone so soft-spoken and sociable.

“A lot of people call me a gentle giant,” Johnson said, “so definitely the monster is like a fuzzy monster.”

Often that monster needed prodding to emerge. His teammates challenged him to become more assertive last season while helping Rutgers reach the NCAA tournament for the first time since 1991.

“It’s kind of hard to see yourself becoming that if you don’t see someone like you in that area.”

— UCLA center and engineering student Myles Johnson

A similar dynamic played out in engineering classes where Johnson starred in the shadows.

“I think what I respect about him the most is that he’s probably one of the most humble and down-to-earth students that I’ve had,” said Mehdi Javanmard, an associate professor in electrical and computer engineering at Rutgers. “Maybe even myself, I’d probably have an ego the size of this building that I’m sitting in right now if I was on that career path and have NBA potential and was doing everything that he is.”

Johnson announced in April that he would complete his college career at UCLA, enticed by a top graduate program in electrical and computer engineering, a basketball team coming off an unexpected Final Four run and a 30-minute commute home without traffic. He has two years of remaining eligibility and may use them both depending on the feedback he receives after next season about his NBA prospects.

Local basketball fans saw the monster surface in a Drew League game this summer. Johnson broke a rim with a vicious dunk, calling it every big man’s dream.

“All centers,” he said, “eventually want to break a rim or two.”

::

Johnson’s arrival in Westwood could help reverse a troublesome trend off the court.

Among UCLA’s domestic student population, Black students made up 8.1% of graduate students for fall 2020, the most recent period for which statistics are available. The proportion of Black graduate students in STEM fields was 7.6%, including 4.0% for the Samueli School of Engineering.

As of this fall, only five of the 191 faculty members (2.6%) in the school of engineering are Black, up from two as of 2019. School officials say they have initiated programs to improve diversity while being constrained by Proposition 209, the California law that prohibits race from being used as a factor in public education hiring practices.

Efforts to increase minority representation among students include supplemental math instruction in high school and introductory robot coding sessions intended to stimulate interest in engineering.

“Probably the biggest hurdle is a lot of our [prospective] students aren’t getting the level of education they should be getting because they attend underserved schools,” said Scott Brandenberg, a UCLA engineering professor who previously served as the engineering school’s associate dean for equity, diversity and inclusion. “There’s just huge discrepancies in resources available to local public schools.”

Johnson was uncomfortably familiar with the fallout from those discrepancies. As he pondered his mother’s question about his legacy, he scanned the list of Fortune 500 chief executives, searching for faces resembling his own. He found only three and considered the improbable path for Black children who wanted to become the next Bill Gates or Jeff Bezos.

“It’s kind of hard to see yourself becoming that,” Johnson said, “if you don’t see someone like you in that area.”

That was a conundrum Johnson figured he could help solve. He would inspire others to follow his size-17 footsteps toward a career in engineering.

Johnson told his mother of his plans the day after her challenge, answering her question with one of his own: How do nonprofit foundations work? The one he envisioned would try to make fields that had largely excluded Black students more welcoming.

What is going to be your legacy? More than basketball.

::

The first steps involved some stumbles.

Johnson didn’t know much about starting a nonprofit, his mother having to explain that it would require money upfront. A cousin who was an attorney advised him of the legal maneuvering required, and he found a company to help with the paperwork.

The first snag came when Johnson discovered the name he wanted — Codeblack — was taken by a film studio in Santa Monica. He quickly pivoted to BLKdev.

“It rolled off the tongue pretty well,” he said, “and in the engineering world, you always shorthand development for dev.”

NCAA compliance presented another hurdle. Rutgers initially told Johnson he couldn’t have his name associated with the nonprofit before relenting with the caveat that he couldn’t raise money prior to the launch of name, image and likeness deals this summer.

UCLA is No. 3 in the Pac-12 women’s basketball coaches’ preseason poll and USC is ninth. Follow along for more updates from media day.

Johnson designed the website himself, using a tool that did most of the coding. The site, blkdev.org, launched on June 11, 2020, and quickly developed a loyal following with the help of his girlfriend, Jabria Baylor, who helped promote it via social media.

“I go on there to look for scholarships and new resources that he’s always adding,” said Joe Barr, a Rutgers engineering major. “I have it bookmarked.”

The site started as an information bay, hosting links to educational resources, scholarship funds and Black STEM news. It also showcases stories of Black students and professionals in STEM fields intended to inspire others.

“Looking back,” Johnson wrote in his biographical blurb, “I would tell children who are on the fence about pursuing STEM that there is such a wide range of possible professions, not just coding, or machinery, which comes to mind when hearing ‘engineering.’ The world of opportunities is never-ending.”

::

BLKdev remains in its infancy, with Johnson intending to expand its reach. He hopes to hold free coding camps online and later in person once COVID-19 restrictions loosen. He also wants to show high school students that STEM doesn’t just involve coding and robotics; one can make a new toothpaste formula or design a line of makeup.

Now that name, image and license legislation has freed college athletes to endorse products, Johnson is exploring additional ways to expand and promote his foundation. One idea is partnering with IBM after recently completing an internship in firmware development. His work for the company entailed devising micro code that functions as software that can run securely inside hardware as part of IBM’s confidential computing efforts.

“There may be a right time in the future for collaboration between IBM and Blackdev,” said Ross Mauri, general manager of IBM Z. “We’ll just have to see how it grows up, but I have pretty high hopes that someone with his vision and his determination, he’s going to see it through, he’s going to see it grow and there’s going to be a great crop of students that will be engaged in it and we’ll want to participate in that and support it.”

Johnson’s hope is that BLKdev can become the next Black Girls Code, which has attained a worldwide following over the last decade after securing a host of corporate sponsors. Playing in the NBA, as Johnson intends to do, would provide a massive bump in exposure.

Once his basketball career ends, Johnson wants to work in hardware design, reducing the carbon footprint through cleaner energy sources. That could involve designing more efficient solar panels or car batteries, among other possibilities.

If he inspires someone by making the NBA, that’s great. But he can imagine something more rewarding.

“Just to hear like, ‘Oh, my little kid wants to be an engineer now because he sees you’re an engineer,’ that, for me, is more rewarding than like, ‘Oh, now he wants to play basketball’ because there’s a million people that want to play basketball.”

What is going to be your legacy? Be like Myles has a nice ring to it.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.