Behind the Story: I wanted to know how a Texas Ranger got a serial killer to spill his secrets

- Share via

DECATUR, Texas — Late last year I wrote a story about how the FBI and local police determined that Samuel Little was a serial killer.

I interviewed detectives and FBI analysts, but one major player in this drama was missing — the Texas Ranger who got Little, 79, to confess to having strangled 93 people during a decades-long killing spree.

I have long been fascinated by detective stories. As a police reporter in Baltimore and Washington for five years, I frequently trailed detectives as they investigated crimes ranging from slayings to burglaries. I even embedded with a homicide squad for a book I wrote about the craft of police work.

Texas Ranger James Holland’s interrogation of Little is one of the most consequential in policing history, and I had so many questions. How did he convince Little to talk? How did he build a rapport with someone who killed with such ease? How did he succeed where so many other investigators had failed? What did he make of the killer?

I emailed and called Holland over the next six months asking to sit down with him. In June he invited me to Texas. “We can visit for a bit,” he told me. In July and August, I interviewed him over the course of four days.

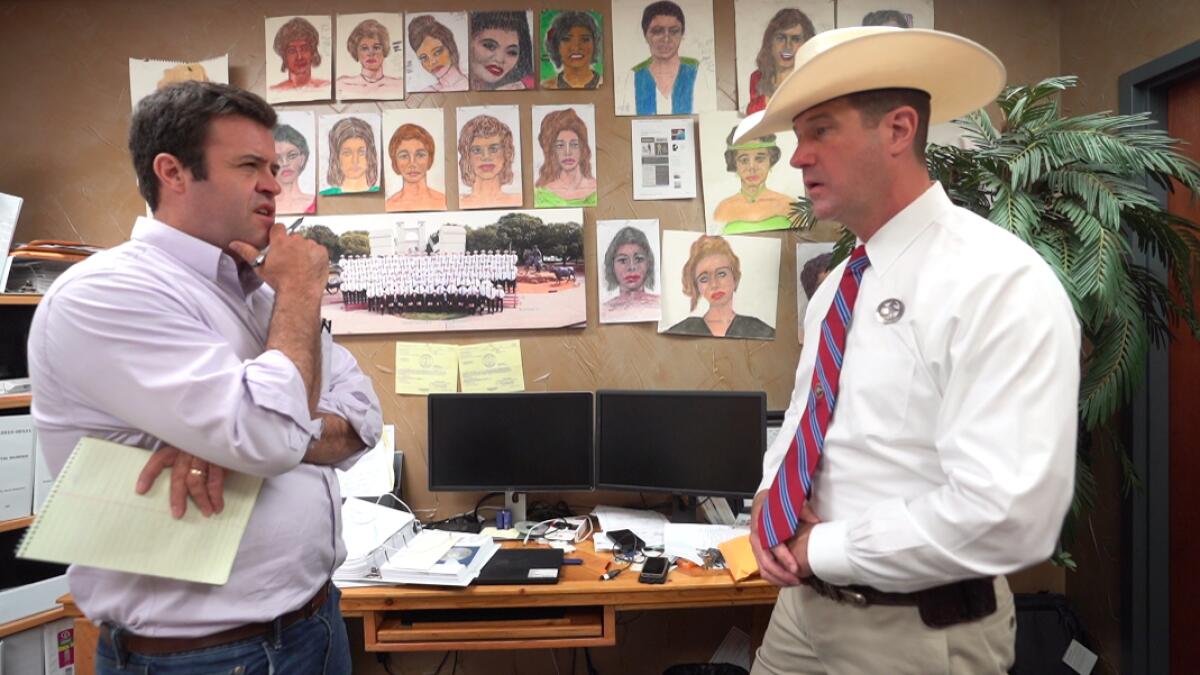

I don’t want to spoil the story, but Holland answered all of my questions as I interviewed him in his office, which he had lined with 52 vivid portraits rendered by Little of his victims.

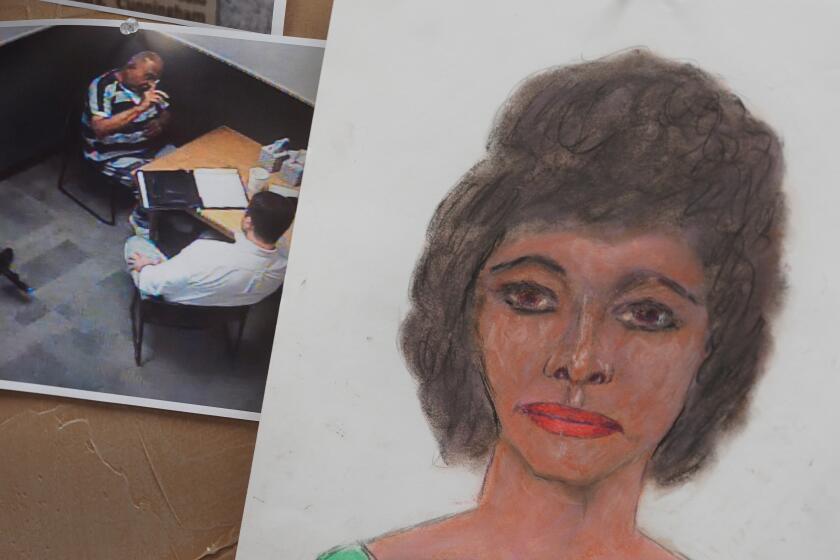

He also let me watch videos of him questioning Little and walked me through how he got Little to start talking.

In the process of trimming the piece, I had to delete a few nuggets and compelling stories. This one says a lot about how Holland was able to confirm so many of Little’s confessions:

When Holland first got Little to confess, the serial killer mentioned having strangled a prostitute in a town south of Wichita Falls, Texas. Little said he drove the woman to a weed-strewn field where he killed her and dumped her body. He was within sight of a church with a steeple.

Holland was particularly interested in solving this strangling because it had occurred in his own backyard in northern Texas, and Little provided enough details that Holland didn’t think it would be too hard to corroborate. Then he hit a brick wall.

Wichita Falls police and others in the area had no cases like it. Over more than 650 hours of interviewing Little, Holland returned to this case at least 30 times, trying to find a detail that might lead to a victim.

First, Holland cleared up problems with geography. He showed Little a map of Texas, and the killer admitted he had confused Plano with Plainview in an earlier interrogation. The two cities are 300 miles apart. Thanks to other clues provided by Little, Holland was able to narrow the killing to somewhere between Amarillo and Lubbock, which are about 200 miles west of Wichita Falls.

Little initially placed the killing in the 1970s. But Holland knew Little was terrible at dates. He spent much of his time interrogating Little by trying to narrow down the time frames of slayings.

One way he learned to do this, Holland told me, was to appeal to Little’s love of cars. He was a car fanatic. He could recall everything about the cars he had owned. In this case, he recalled driving a Cadillac Eldorado, which he had purchased in 1993 shortly after being released from a Florida jail. That detail narrowed the killing’s time frame to the early 1990s.

Holland reached out to police agencies in western Texas. They were already scouring files for cases that might match Little’s M.O. — strangling victims who were left partially clothed and not far from roads.

A detective in Lubbock, Brandon Price, found three homicides that he thought might have been committed by Little. He ruled out two. The third had potential, but the autopsy asserted 37-year-old Bobbie Ann Fields had died of blunt-force trauma to the head.

Price dug further into the autopsy and found a notation that suggested Fields may have been strangled. She had also had previous brain surgery. Could the woman have been injured during a strangling in such a way that it looked like a fatal blow but wasn’t? Maybe she suffered her mortal head injury while Little was choking her?

Price reached out to the FBI and Holland. Holland explained how Little had described picking up the prostitute and the route he drove to the murder scene. Price confirmed that was precisely the route the killer would have taken.

Price uncovered a statement from a witness who said he had watched Fields get into a 1978 yellow Cadillac Eldorado — the same type of car Little had been driving at the time. The witness’s description of its driver matched a mug shot taken of Little just weeks earlier, Price said.

In August, Holland and Price interviewed Little in California, and Little identified Fields as his victim from photographs.

To be certain, the detectives placed a map of Lubbock in front of Little that had been scrubbed of most identifying markings; neither investigator wanted to feed any information that might call a confession into question. With no prompting, Little pinpointed the exact spot where police had found Fields.

“It shocked me,” Price said. “It was just eerie.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.