By his count, Washington attorney general hasn’t lost a case against Trump yet

- Share via

SEATTLE — When President Trump announced his original Muslim travel ban on a Friday in early 2017, Washington Atty. Gen. Bob Ferguson spurred his deputies on a weekend blitz so his state could be the first to challenge it.

“‘If at all humanly possible, we need to file the suit on Monday,’” Ferguson recalls telling his team. “I didn’t want there to be one business day that went by when the people of my state would think I thought that the travel ban was OK.”

Almost three years later, Ferguson, a chess whiz and obsessive scorekeeper, remains one of the nation’s most activist Democratic state attorneys general, suing the administration 50 times to date. He picks his fights, trailing his California counterpart, Xavier Becerra, who’s racked up 62 suits on issues such as immigration, the environment, gun control, consumer protection and civil rights.

Becerra, Ferguson and attorneys general in a handful of other states, notably Massachusetts and New York, are leading the charge in filing an unusual number of cases against a president. Jonathan Turley, a constitutional law professor at George Washington University, says the trend results partly from “shoddy” legal work by the administration — the travel ban took multiple versions to pass muster in court — but also from political posturing by state officials.

“There’s an exponential explosion of attorneys general lawsuits, and many of those lawsuits have failed,” Turley said. “For Democratic attorneys general, lawsuits against Trump have become a badge of legitimacy.”

But when state Republican lawmakers accuse Ferguson of grandstanding, he defends his record, sending them detailed allegations of constitutional violations and harm to Washington citizens. By his reckoning, he’s won 22 cases, 13 of which are resolved beyond appeal, and lost none.

The track record is “a good indication that we’ve been disciplined in bringing the right cases,” he said.

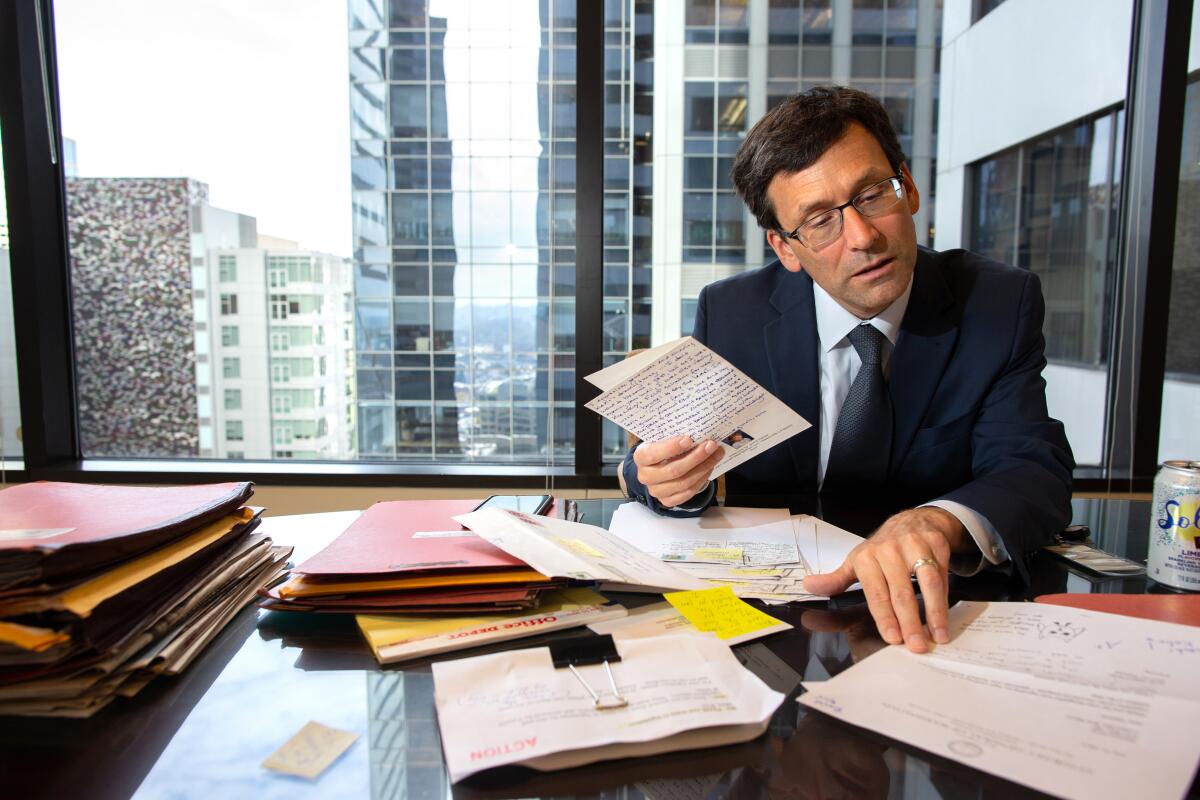

Ferguson, 54, slim and bookish with glasses and graying brown hair, is a calm, reasoned public speaker. At 5-foot-11, he’s three inches shorter than Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, who often stands with Ferguson at news conferences announcing suits, lobbing more incendiary potshots at Trump. Ferguson was considering a run for governor until Inslee dropped his presidential campaign and declared for a third term.

Ferguson is athletic and driven, always with an eye on numbers. He aims to climb to the highest point in each state, with five to go, including Denali, the tallest peak in North America. He’s a dozen sandwiches away from speaking at each of Washington’s 182 Rotary clubs.

The habit of setting audacious goals began young, developing after Ferguson graduated from the University of Washington and served in the Jesuit Volunteer Corps, helping low-income residents of Portland, Ore. He spent six weeks on the road in a balky Honda with a college buddy, Brian Bennett, seeing a ballgame in every Major League stadium.

Bennett, a Seattle lawyer, said Ferguson shows determination, whether summiting Washington peaks or working on his lifetime bird-watching list. “Bob has a level of self-discipline which I’m not sure I’ve ever seen in anyone else,” he said.

Politics ran through Ferguson’s veins before he was born. A photo on the wall of his 21st-floor Seattle corner office shows his father and mother, pregnant with him as her sixth child, posing with a governor-elect at a campaign celebration.

Ferguson’s dad, a Boeing facilities planning manager, knew nothing of rooks and pawns, but began taking him at age 9 to the company chess club, where the youngster soon checkmated adults. After high school, Ferguson played chess across the United States and Europe for a year, playing a grandmaster to a draw in a 10-hour game at the Berlin Open, but ultimately deciding not to go pro.

“It’s a solitary endeavor, and you’re not exactly changing someone’s life,” he said of professional chess. But he said the game taught him how to take calculated risks and not blame others. “The biggest strength I had,” he said, “was that I hated to lose.”

Ferguson counts coups during two terms as attorney general, with verdicts including an $18-million judgment against the Grocery Manufacturers Assn. for concealing its identity as a state campaign donor. He won a judgment of more than $9 million against Comcast for overcharging customers. He has the first trial in the nation coming up in February against Purdue Pharma, having declined to enter a tentative settlement in a case accusing the company of fueling the deadly opioid epidemic.

With a staff of more than 1,000, Ferguson runs the nation’s fifth-largest state attorney general’s office. He has created a civil rights team, beefed up an antitrust unit and expanded a consumer protection squad that he plans to build into the biggest in the country. He said that suits against the Trump administration cost taxpayers a negligible amount because they’re funded by proceeds from civil enforcement.

Ferguson applies three tests when deciding whether to sue the administration. He asks whether Washington residents are being harmed, whether his arguments are good and whether the state has legal standing.

“If the answers are ‘yes,’ ‘yes’ and ‘yes,’ we file the lawsuit,” he said. “If there’s a ‘no’ in there, we don’t.”

Of the 50 he’s filed, 26 challenge Trump on the environment, including the most recent case last week accusing the administration of undermining the Endangered Species Act. Eleven are immigration cases, such as a suit challenging the constitutionality of separating families along the southern U.S. border. Washington is the lead plaintiff in 18 cases, including that one.

Ferguson sees his challenge to Trump’s first travel ban as the most significant, one that he feels set a tone and helped empower other states. A judge granted a nationwide temporary restraining order, which the 9th Circuit appeals court upheld, and the administration rescinded the ban.

Ferguson counts the case as a win, saying that no court has ruled against the merits of his arguments in suits against the administration. “I’ll be surprised if I ever have a successful outcome that matches that,” Ferguson said.

But Turley pointed out that ultimately the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the travel ban’s third version, accepting the administration’s claim that it served a national security interest. By the law professor’s count, about half of Ferguson’s suits have succeeded so far. He said that many have duplicated litigation brought by organizations and individuals.

Turley granted, however, that some of the suits filed by Ferguson, Becerra and other attorneys general are legitimate, such as the one asserting rights of states to set tougher auto emissions standards than federal requirements.

The president hasn’t singled out Ferguson in a tweet. But when U.S. District Judge James L. Robart ruled in Washington state’s favor on the original travel ban, the president called the jurist appointed by Republican President George W. Bush a “so-called judge.”

Among ongoing cases, Ferguson considers most significant his suit with other states to halt Trump’s decision ending the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program, which protects many young immigrants from deportation. Washington state has about 17,000 of these “Dreamers,” and the attorney general has heard from many.

When Ferguson receives handwritten letters from constituents affected by his Trump lawsuits, he pens them replies. Children writing him often get additional notes from his daughter, Katie, 11-year-old twin to son Jack.

Katie also hand-draws campaign buttons for her father’s current bid for a third term. The two sit together at the dining-room table in a modest one-story Seattle house where Ferguson and his wife, Colleen, an international education advisor, are raising their family.

Ferguson said he loses no sleep over potential retaliation by Trump against his state. “Why worry about it? I don’t control it,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.