The impeachment process, no matter how frequent, is never the same

- Share via

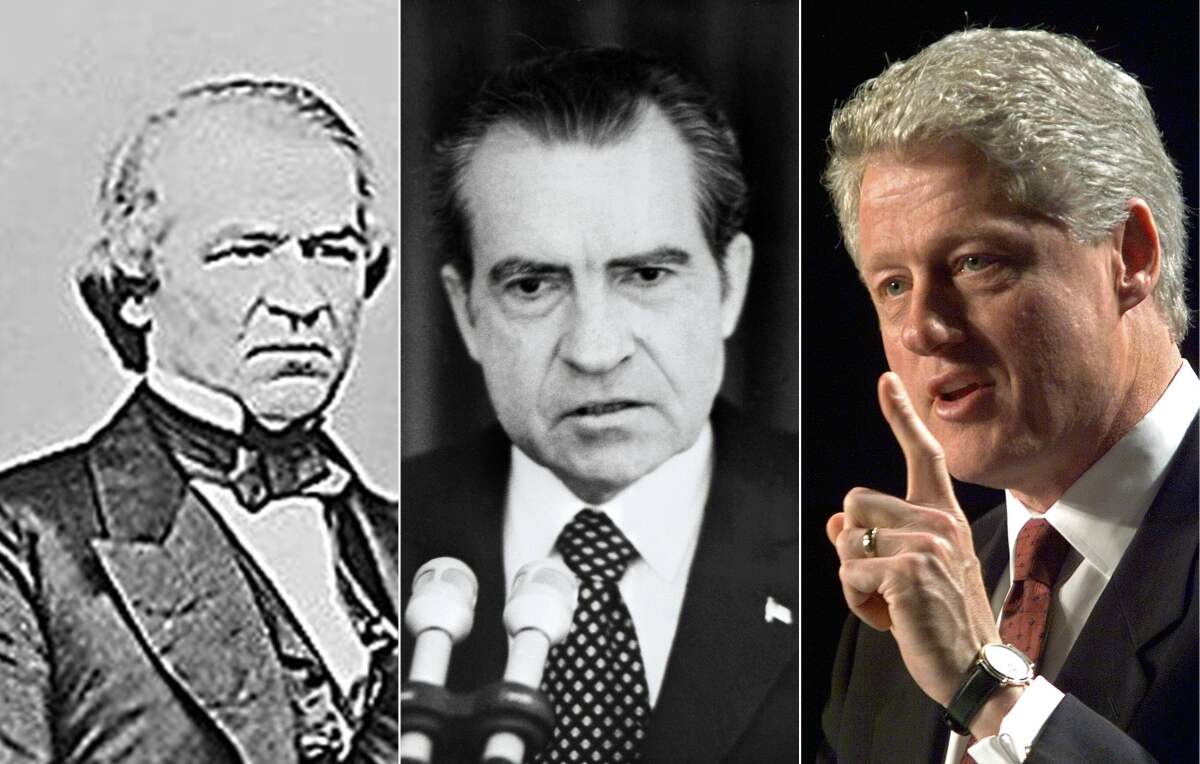

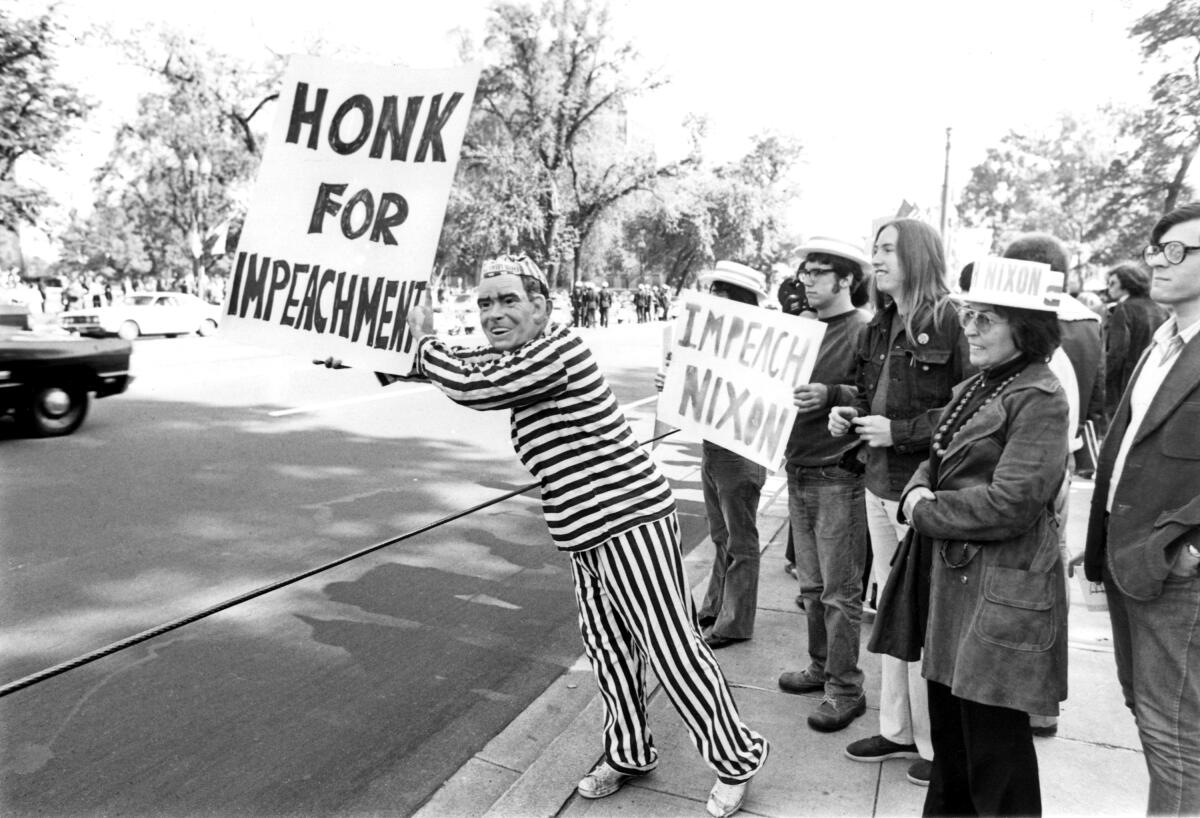

For more than 100 years, between the presidencies of Andrew Johnson and Richard M. Nixon, no Congress even contemplated impeachment. Now the country is hurtling toward its third such drama in less than half a century. Although the process may have a familiar feel to contemporary Americans, the circumstances surrounding each case are unique.

Donald J. Trump isn’t Bill Clinton. Trump isn’t Nixon, either. Though both the Nixon and Trump episodes involved political schemes, the Watergate break-in and the Ukraine communications have nothing in common. Though Trump and Clinton both may have been accused of being serial adulterers, the rage that 21st century Democrats have about Trump’s comportment bears no relation to the fury 1990s Republicans had for Clinton’s behavior.

All these impeachment comparisons fall apart for those reasons — and for far more significant ones:

The United States of Nixon’s 1974 (population 214 million) was a far different place than Clinton’s 1998 America (270 million) and a far, far different country than Trump’s 2019 nation (327 million).

The percentage of Americans who owned a cellphone in 1974 was zero, climbing to 36% in 1998 and beyond 80% today.

Total daily newspaper circulation during Nixon’s impeachment process was 63 million, falling to 56 million during Clinton’s trial and dropping to half that amount amid Trump’s current scandal. Three news magazines helped set the American conversation in the Nixon years; Time and Newsweek, in particular, tortured the 37th president. Today, only Time can be regarded as a mass-media publication, and its impact is greatly diminished.

Social media platform Twitter, nonexistent during the earlier presidential dramas, is a prominent part of the Trump presidency.

The Congress that may impeach Trump also is operating in a far different world than that of his besieged predecessors.

Congress’ approval rating stood at 35% during the Nixon resignation year and was at 42% during the Clinton impeachment, according to Gallup polling. Those figures are Himalayan compared with congressional approval today. The Congress that may impeach Trump has an approval rating of 18%.

Both Nixon and Clinton thought of themselves as readjusting American politics and culture, the former by restoring American purpose in the Vietnam years and the latter by bringing a fresh, generational change to Washington. But neither was at heart a disrupter; the one element of Trump’s political profile that Republicans and Democrats, liberals and conservatives, can agree upon is that he is bringing dramatic change to electoral and Washington politics.

Nixon and Clinton — mainstream figures with conventional political backgrounds — would have been happy simply to drain the capital of, respectively, big-government New Deal bureaucrats and Reagan-Bush skeptics of the primacy of government in society. Trump, with the most unconventional pre-presidential resume in history, ran on a platform of draining the entire swamp.

The two previous impeachment targets wanted merely to wrest control of the Deep State. Trump wants to eliminate it.

And the circumstances surrounding the Nixon crisis (a breathtaking coverup of illegal activities growing out of a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office complex) and those surrounding the Clinton crisis (mendacity following a sordid tryst with a White House intern) have no common ground with the drama unfolding on Capitol Hill around Trump.

Moreover, Trump faces an impeachment threat because of events overseas, one of the principal rationales for including the impeachment power in the Constitution. In the 68th essay of the Federalist Papers, documents written to push ratification of the U.S. Constitution, Alexander Hamilton wrote that impeachment was a necessary element in the new republic to counter “the desire in foreign powers to gain an improper ascendant in our councils.”

The big difference between the 1974 and 2019 episodes, the two most frequently compared today: The Watergate coverup followed a crime in which the president was not involved, while the alleged Ukraine coverup followed an action in which the president was directly involved.

Nixon never was impeached; he resigned in August 1974 as he faced certain impeachment in the House and likely conviction in the Senate. Clinton was impeached but survived a Senate trial in 1999. Even if Trump is impeached, he is unlikely to be forced from office given the difficulty of achieving a two-thirds majority in a Senate controlled by Republicans.

In many ways, the tone and timbre of impeachment are determined by the character of the moral leader of the effort in the House.

In Johnson’s time, it was Rep. Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania (a fiery opponent of slavery and advocate of Radical Republican Reconstruction), followed in Nixon’s time by House Majority Leader Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill of Massachusetts (celebrated in Jimmy Breslin’s “How the Good Guys Finally Won”) and in Clinton’s time by House Speaker Newt Gingrich of Georgia (an academic historian turned GOP maverick and Alvin Toffler acolyte).

Now the principal figure is the onetime reluctant impeachment warrior, Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi of San Francisco, a devoutly conventional politician who is a fervent opponent of Trump but in many ways more cautious than her impeachment predecessors.

One element alone ties together the four drives toward impeachment — the sense, which author Brenda Wineapple conveyed vividly in her account of the Johnson impeachment, published only five months ago, that congressional impeachers “knew, or wanted to believe, that impeachment implied hope, the glimmering hope of a better time coming, a better government, a fairer and more just one.”

But the key to understanding the country’s passage since Johnson’s 19th century agony (in which he escaped conviction by a single vote in the Senate) comes not from history, nor from journalism, nor from political science, nor even from psychology. It comes instead from literature, and from Russia.

For it was around the time of the Johnson impeachment that Tolstoy wrote “Anna Karenina” and, to adapt a deathless insight from the book — like the history of all impeachments, including this one, written in installments — it is clear that every impeachment is unhappy in its own way. We surely will discover that in our own time.

Shribman is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.