Giuliani’s conspiracy theories cost this anti-corruption lawmaker in Ukraine his job

- Share via

KYIV, Ukraine — Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s team realized it had a potential problem in U.S. relations on May 10, when Rudolph W. Giuliani told Fox News that a Ukrainian advisor to the newly elected leader was a Trump enemy.

“I’m convinced that [Zelensky] is surrounded by people who are enemies of the president, and one person in particular, who is clearly corrupt and involved in this scheme,” Giuliani said.

The former New York mayor, now serving as President Trump’s private attorney, was talking about Sergei Leshchenko, a young member of parliament and former investigative journalist who was in line for a top position in the Ukrainian president’s new administration.

The next day, Leshchenko was dismissed from consideration for Zelensky’s team.

Zelensky’s advisors understood that Giuliani was a mouthpiece for President Trump, and the last thing the new Ukrainian president wanted was a sour start with the White House.

“For the new president, it was impossible to have such a negative narrative with an American president at the very beginning,” Leshchenko said. “So, it of course had a bad impact on my political prospects with Zelensky’s team.”

From that moment, Leshchenko became the focal point in Giuliani’s campaign to push conspiracy theories involving Ukraine. But what was at the heart of Giuliani’s narrative was a mysterious accounting book that became known as “the black ledger.”

In 2016, Leshchenko was part of a group of young politicians pushing for democratic reforms in Ukraine. In his former life as a journalist, he had developed a reputation for hard-hitting reporting that exposed high-profile corruption cases.

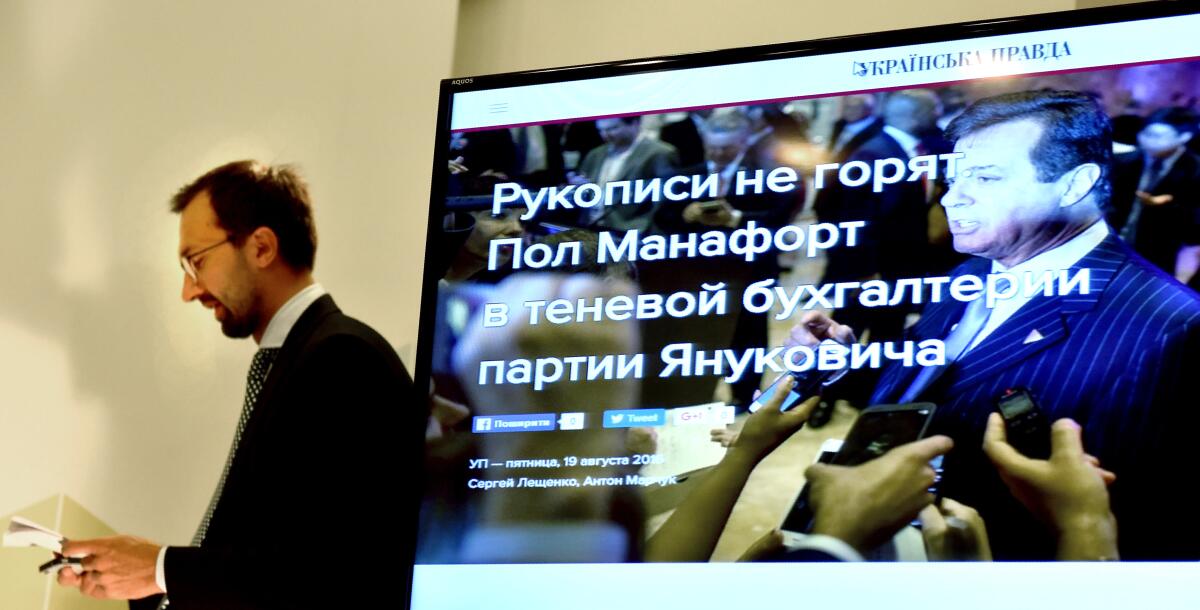

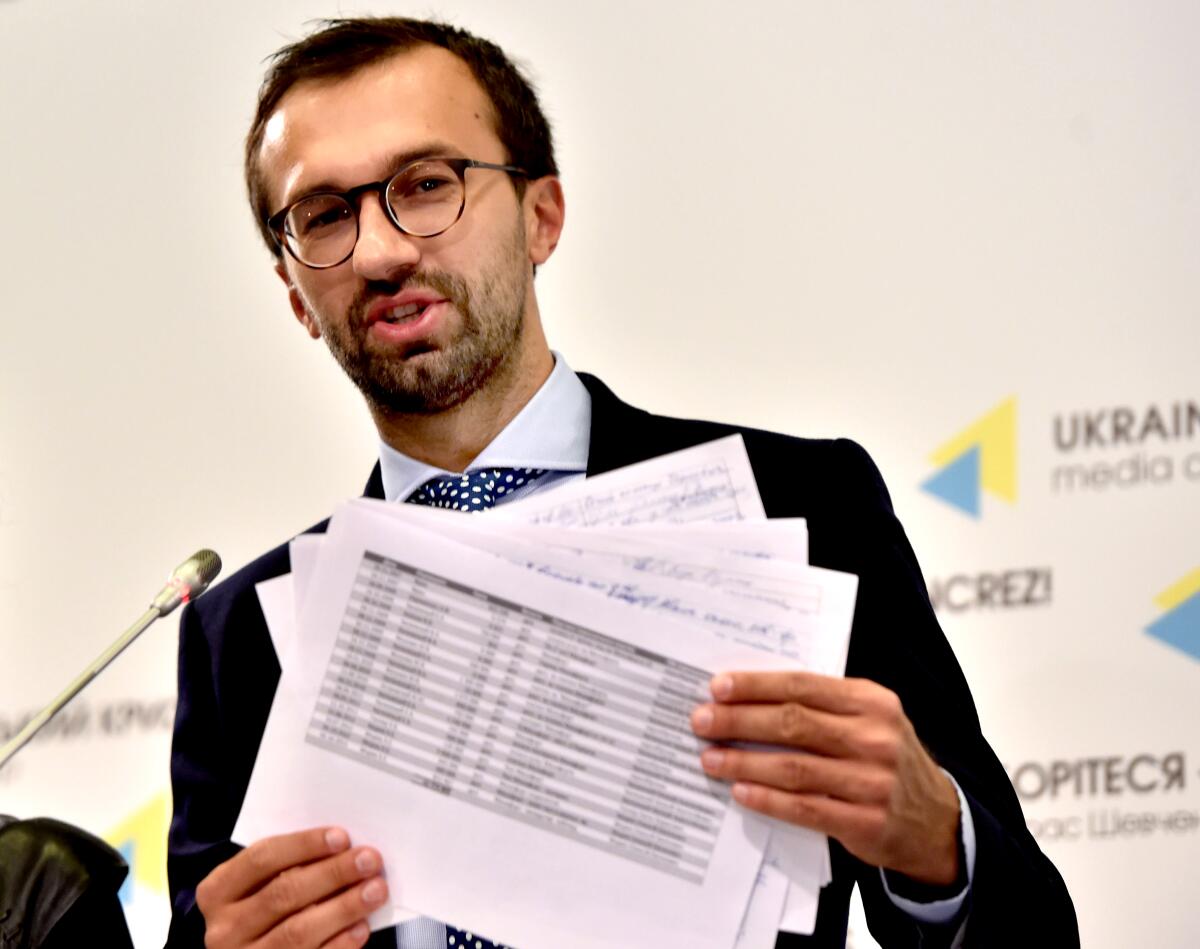

That August, Leshchenko held a news conference in Kyiv to disclose the existence of a notebook found in a burned-out room in the headquarters of Ukraine’s former ruling political party. The book revealed a list of purported secret payments made by Ukraine’s former pro-Russia president, Viktor Yanukovich, to Trump’s onetime campaign chairman, Paul Manafort.

Leshchenko certainly had reason to dislike Manafort. Before joining Trump’s election campaign in 2016, Manafort had worked as Yanukovich’s consultant. Leshchenko and other anti-corruption, pro-reform leaders in Ukraine blamed Manafort for helping Yanukovich get elected in 2010. The president then used his position to get rich by stealing from Ukrainian government coffers.

In 2013, government corruption had helped ignite the Maidan street revolution in Kyiv. Yanukovich fled to Russia, which occupied and annexed Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula a month later. Moscow continues to support a separatist insurgency fighting Ukrainian government forces in the east.

A U.S. federal court in March sentenced Manafort to 7½ years for fraud and money laundering, some of which stemmed from unreported payments from Ukraine.

Manafort’s imprisonment came out of special counsel Robert S. Mueller III’s investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. election. Trump has called the investigation a “witch hunt.”

When President Trump’s former campaign chairman wants to call his lawyers from jail, he doesn’t have to line up at a pay phone.

Trump blamed Ukraine for Manafort’s troubles, saying the incident proved that Ukraine “tried to take me down.” He started pressing for an investigation into alleged Ukrainian interference in the 2016 election. U.S. intelligence agencies had established that Russia, not Ukraine, had meddled in the election.

By May, Leshchenko was in Giuliani’s sights.

In a series of interviews on Fox News and CNN, Giuliani accused Leshchenko of colluding with Democrats to interfere in the election. By Giuliani’s accounts, Ukrainians — namely Leshchenko — conspired with Democrats to focus attention on Manafort’s business in Ukraine in an attempt to cripple the Trump campaign.

Giuliani called the black ledger a “complete fake.”

Leshchenko denies Giuliani’s accusations. He said he was shocked when he realized Trump’s personal lawyer was dragging Ukraine into the fray of Trump’s 2020 reelection campaign and trying to bring Leshchenko’s reputation down with it.

“This story intoxicated the whole U.S.-Ukraine narrative,” said Leshchenko, a tall, thin 39-year-old with the look of a college professor.

Zelensky, a former comedian with no previous political experience, was elected in April with more than 73% of the vote.

“I support him, and I like his way to destroy this establishment of cronyism and corruption, which was very destructive for Ukraine for the past 25 years,” Leshchenko said.

Leshchenko said he understood that if the Trump White House viewed Leshchenko as part of Zelensky’s team, it would be damaging for the new Ukrainian president, so he agreed to drop out of the running to join the new administration.

“I told [Zelensky] I cannot keep you as a hostage of my problems with Giuliani,” he said.

Zelensky should keep his distance, Leshchenko added: “Ukraine needs bipartisan support in America. We don’t need to be in the middle of a U.S. political scandal.”

Trump has hinted that he believes Ukraine is harboring a computer server containing emails sent by former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the president’s Democratic opponent in the 2016 election.

The email landed in John Podesta’s crowded inbox around March 19, 2016, during the height of the presidential primaries, and it appeared to be a standard security request from Google for Hillary Clinton’s campaign chairman to change his password.

So far, no evidence has emerged to support any of these accusations or theories.

On Thursday, White House acting Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney seemed to confirm that Trump’s administration was still firmly holding on to many of the false narratives about Ukraine spun by Giuliani and other Trump allies.

At a news conference in Washington, Mulvaney said Trump had frozen about $400 million in security aid to Ukraine as a way of pressuring Kyiv to investigate allegations that Ukraine was responsible for hacking Democratic Party emails in 2016.

“We all know that place is corrupt,” Mulvaney said about Ukraine. He defended Trump’s suspension of the security aid, which Ukraine needs in its fight against Russia-backed separatists militias on its eastern flank, saying it was related to U.S. concerns about Ukrainian corruption.

And in particular, Trump wanted Kyiv to investigate his widely debunked theory that the DNC server was still in Ukraine.

“That’s why we held up the money,” Mulvaney told reporters. He later walked back his claim, saying there was no quid pro quo.

Leshchenko, who is no longer in parliament, has tried to dispute Giuliani’s smear campaign against him on social media and even asked some mediators to try to set up a meeting. It wouldn’t be the first time the two have met. In June 2017, a Ukrainian oligarch, Viktor Pinchuk, invited Leshchenko and several other young reform-minded Ukrainian lawmakers to meet Giuliani during a visit to Kyiv.

“He was known then as the former New York mayor, so we all agreed to meet him and didn’t think much of it,” he said, showing a photo on his phone of Giuliani and himself.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.