U.S. couple’s nightmare: Held in China, away from their teenage daughter

- Share via

SHANGHAI — The first thing Daniel Hsu noticed about the room was that there were no sharp edges. The walls were covered with beige rubber, the table wrapped in soft gray leather. White blinds covered two barred windows.

Five surveillance cameras recorded his movements, and two guards kept constant, silent watch. They followed Hsu to the shower and stood beside him at the toilet.

Lights blazed through the night. If he rolled over on his mattress, guards woke him and made him turn his face toward a surveillance camera that recorded him as he slept. He listened for sounds of other prisoners but heard only the occasional roar of a passing train.

“First, keep healthy,” Hsu told himself. “Second, keep strong.”

He had no idea when or how he would get out.

Hsu is a U.S. citizen. He has not been convicted of any crime in China, yet he was detained there for six months in solitary confinement under conditions that could qualify as torture under international conventions. Authorities from eastern Anhui province placed exit bans on Hsu and his wife, Jodie Chen, blocking them from returning home to suburban Seattle in August 2017 and effectively orphaning their 16-year-old daughter in America.

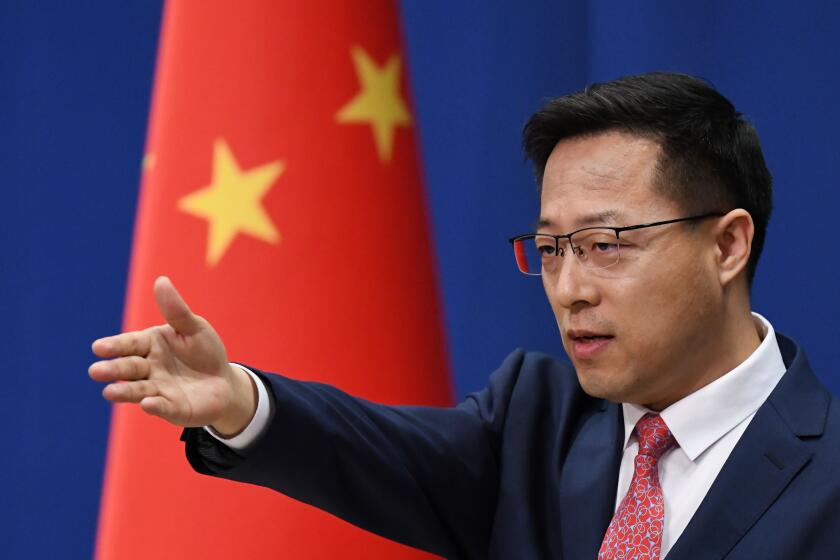

‘Put on a mask and shut up’: China’s new ‘Wolf Warriors’ spread hoaxes and attack a world of critics

The aggressive nationalism of China’s diplomats matches the swagger of Xi Jinping’s China, which is determined to deflect blame for the coronavirus.

Critics say the Chinese Communist Party’s expanding use of exit bans to block people — including U.S. citizens and permanent residents — from leaving China reeks of hostage-taking and collective punishment. They also warn that it lays bare China’s will to exert influence not just over Chinese citizens in China, but also permanent residents and citizens of other countries.

“American citizens are too often being detained as de facto hostages in business disputes or to coerce family members to return to China. This is shocking and unacceptable behavior by the Chinese government and a clear violation of international law,” said James P. McGovern, chair of the bipartisan Congressional-Executive Commission on China.

Hsu says Anhui authorities have been effectively holding them hostage in order to convince his father, Xu Weiming, to come back from the U.S. and face charges he embezzled 447,874 yuan (worth $63,000 today) more than 20 years ago — an allegation Xu denies.

The COVID-19 pandemic has added grave new urgency to their desire to leave. Despite fear of retribution, the family is speaking out for the first time, offering a rare account of life inside China’s opaque system of exit bans and secretive detention centers.

Their story is supported by Chinese court documents and correspondence and interviews with U.S. and Chinese government officials. Some details could not be independently verified but are in line with accounts from other detainees.

When the coronavirus outbreak began in China, many other nations blocked Chinese travelers. Now China is raising its guard against outside infections.

Five days before Hsu entered the smooth beige room at a Communist Party-run “education center” in Hefei, the capital of Anhui province, his stepdaughter, Mandy Luo, boarded a flight from Shanghai to Seattle alone. She had been on a family visit to China and was supposed to return with her mother to finish high school. But airport security had blocked her mother from boarding.

Mandy vomited for 10 hours on the flight home. “Mom,” she kept thinking, “why are you not here?”

The answer to that question lies in Chinese laws that give authorities broad discretion to block both Chinese citizens and foreign nationals from leaving the country. Minor children, a pregnant woman and a pastor — all with foreign passports — have been banned from exiting, according to people with direct knowledge of the cases.

The U.S., Canada and Australia have issued advisories warning their citizens that they can be prevented from leaving China over disputes they may not be directly involved in.

“U.S. diplomats frequently raise the issue of exit bans and the need for transparency with the PRC government,” a State Department spokesperson said in an email. “The Department has raised Mr. Hsu’s case at the highest levels and will continue to do so until he is allowed to return home to the U.S.”

Within China, exit bans have been celebrated as part of a best-practices toolkit for convincing corrupt officials to return to China for prosecution, part of President Xi Jinping’s sweeping campaign to purify the ruling Communist Party and shore up its moral authority. Many corruption suspects fled to the U.S., Australia and Canada, which do not have extradition treaties with China.

Requests for comment to Anhui province’s Commission for Discipline Inspection and Supervision, Public Security Department and procuratorate, as well as the province’s foreign affairs and propaganda offices all went unanswered. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Beijing declined to comment.

China’s Communist Party on Tuesday affirmed President Xi Jinping’s status as the most powerful ruler since Mao Tse-tung, handing the authoritarian leader even greater control to enact his nationalist vision of a resurgent China.

Hsu was accused of being a co-conspirator in the corruption case against his father, Xu. The Hefei Intermediate People’s Court found that Xu embezzled money for real estate in the 1990s while serving as chairman of Shanghai Anhui Yuan Industrial Corp. At the time, Hsu was half a world away, studying accounting at the University of San Francisco.

Xu denies the charges. In a letter to the court, he wrote that the money was a housing stipend, vetted by a government audit committee and awarded to dozens of employees. He said he is the target of a political vendetta.

“If my dad’s rich, OK, I deserve this maybe,” said Hsu, who ran a barbecue restaurant in Bellevue, Wash., which he was forced to sell during his involuntary exile. “But I never enjoy anything. I don’t have a Ferrari. I don’t have a yacht. I’m just a small business owner.”

His interrogations came in fits and starts. He gazed at the smooth edges in his room and thought about hurting himself. He fantasized that a Delta Force chopper would rescue him. The men would break through the walls and say, “You’re free, sir. Come with us.” No one came.

“Try to sit in a room for three hours and tell me how do you feel, just by yourself. You have nothing,” he said in an interview.

Before coming to the party education center, Hsu had spent 14 days in detention in Hefei, sharing a cell and one bucket toilet with two dozen men. Hsu asked police to send him back. At least there were other people, TV, chess. Even his cellmate who allegedly murdered his girlfriend was kind of nice.

In mid-September police gave Hsu a phone so he could convince his parents to return. His mother told him they’d written letters to Washington. “Be strong,” she said. “I am proud of you.”

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

After a few days, the phone was taken away. Hsu had been given a mission, to convince his father to return, and he had failed.

Hsu was being held under “residential surveillance in a designated location,” a legal mechanism that allows detentions of up to six months without formal charges or judicial review in certain cases.

The United Nations has urged Beijing to halt the practice, saying it “may amount to incommunicado detention in secret places, putting detainees at a high risk of torture or ill-treatment.”

China is a signatory to the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, which defines torture as an intentional abuse of power by the state that causes severe physical or mental suffering. It signed, but did not ratify, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which precludes torture as well as “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.”

Joshua Rosenzweig, a deputy regional director at Amnesty International in Hong Kong, said that though residential surveillance sounds better than throwing someone in jail, in practice it’s one of the most excruciating forms of detention under Chinese law. In Hsu’s case, he said, prolonged solitary confinement and 24-hour surveillance seemed designed to cause psychological suffering with the aim of coercing him to do something.

“That would clearly satisfy the criteria for torture and other ill treatment,” Rosenzweig said. “The ability, inside a black box, to carry out this kind of coercion against someone — it’s incredible this is allowed to go on.”

Over time, and late at night, Hsu’s guards relaxed. Hsu discovered one was a fan of Manchester United. Others wanted to know what the schools were like America and how much real estate cost. Eventually, he said, he got one guy to bring him a caramel macchiato from Starbucks.

More than 500 coronavirus cases have been confirmed across five prisons in three Chinese provinces. Families fear they don’t have the whole story.

In December, police announced that Hsu’s father had agreed to go back to China. Hsu was shocked. On Dec. 14, a consular officer came with news that his father had made a sworn statement declaring Hsu’s innocence.

His mother also sent word that her husband’s health was poor and he would postpone his return.

Hsu held his fists and began to shake.

The next morning, his minders yelled at him. They made him make a videotaped message. Hsu told his parents they should have kept their word and returned. He wrote a letter, telling them he was getting sick in his head, pulling his hair out, not sleeping.

The new rotation of guards refused to speak to him. He dreamed about his daughter and woke in the night, his face wet with tears.

Back in Seattle, Mandy was also struggling with solitude. But she didn’t want to add to the general misery, so she boxed up the rage and helplessness. Instead of shouting at her relatives, she wept in her family’s big, empty house.

“Why me?” she cried out, to no one in particular. “I’m only 16. What are you expecting of me?”

On Feb. 11, 2018, near the end of Hsu’s sixth month in detention, he was released. His wife, Jodie Chen, drove nine hours to pick him up. They tossed his prison books in a dumpster and went out to dinner.

Hsu watched his wife eat. He couldn’t bring himself to hug her.

After sleeping under blazing lights for six months, he could no longer sleep in the dark. Shanghai’s jostling crowds made him nervous. He kept crying.

Hsu, 43, and Chen, 44, were living off savings. Their marriage was rapidly deteriorating. When they weren’t fighting, they sat at home and stared at each other.

Friends offered Hsu jobs or money to start a restaurant in Shanghai. But he always declined, worried he’d get them in trouble.

The U.S. Consulate in Shanghai lobbied intensively on the couple’s behalf. But nothing changed.

In May 2019, immigration officers came to Hsu’s home and told him they were going to deport him because his visa had expired. They warned him he’d never be able to return to China.

“I said, ‘We can talk about that later, but deport me, please.’”

They didn’t.

In June 2019, Hsu and Chen missed their daughter’s high school graduation. In August, they recruited relatives to see her off to college.

Last month, at the request of Anhui authorities, Chen wrote a formal petition for her exit ban to be lifted.

“I miss my daughter so much, especially at this critical moment,” she wrote. “I do hope to take care of her, side by side, to fulfill my duty as a mother.”

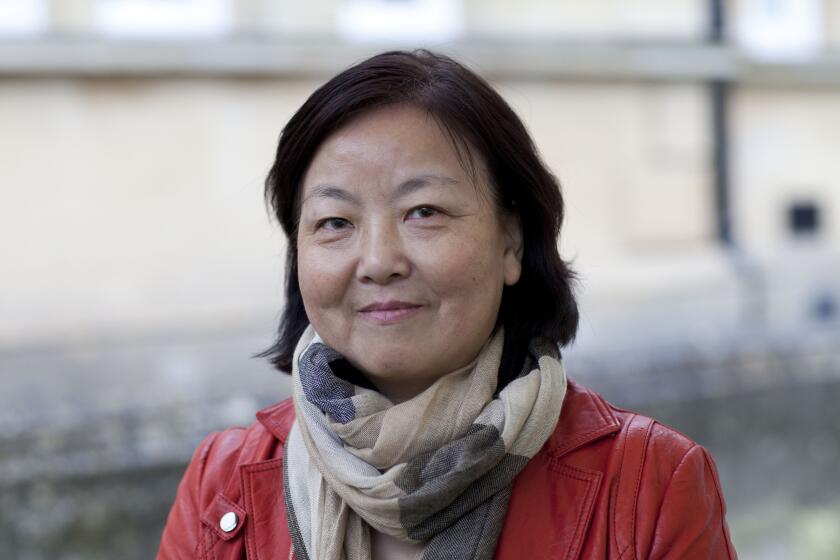

Fang Fang, a novelist from Wuhan, has written an online diary every day under lockdown since Jan. 25. Millions of Chinese readers wait for her updates every night, hungry for an honest voice. Some of her entries are censored by the morning.

She pledged to persuade her father-in-law to return to China, saying she would deepen her emotional bond with her in-laws to establish mutual trust, then explain the “tolerant and humanized approach” of Chinese justice.

It was unclear why Chen’s exit ban was lifted. Hsu would have to stay in China. “They told me if my dad is not coming back, I will never leave this country,” he said.

On April 10, Chen and Hsu rode to Shanghai’s Pudong International Airport in a diplomatic sedan, a small American flag on the hood flapping in the wind. The Shanghai consul general, Sean Stein, escorted Chen to the departure gate.

Chen’s trip back to Seattle took more than 24 hours. Concerned she might have picked up COVID-19 on the journey, she took an Uber from the airport to the leafy cul-de-sac they call home.

It had been 971 days since Chen had touched her daughter. She had planned to self-quarantine for two weeks, but Mandy couldn’t wait. She moved from her grandparents’ house and went into quarantine with her mother.

“It’s 50% over,” Mandy said. “My dad is the other 50%.”

Back in Shanghai, Daniel Hsu went home from Pudong airport and slept most of the day.

When he awoke, he was alone.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.