He’s free for now during the coronavirus outbreak. But a looming prison date has him fearing for his life

- Share via

PHOENIX — These days Johnny Madero almost never leaves the three-bedroom house he shares with his girlfriend and their two young sons.

In the evening, as the unrelenting desert sun disappears, the family sometimes walks to the end of the block and back. It’s never hard to stay more than six feet away from other people.

He takes comfort in knowing his family seems safe, but most nights bring panic. His mind slows and he ticks another day from the mental calendar — one day closer to his nightmare.

Next month, Madero must either accept a plea deal for six years in state prison on a DUI or risk a sentence of 12 to 27 years if found guilty at trial. Madero faces the harsh terms because he is on probation for a 2012 burglary conviction and a subsequent shoplifting arrest. None of the charges have involved violent behavior.

Madero fears, however, that the six years, which he is planning to accept, could prove to be a death sentence if he contracts the coronavirus in the Maricopa County jail or in a rural state prison where he would eventually be transferred.

“I’m terrified to go in there,” the 27-year-old said on a recent afternoon. “This could be the last time I see my family.”

As cases of COVID-19 race through the nation’s overcrowded jails and prisons, attorneys and activist groups have pleaded with judges to release nonviolent offenders already serving time. The rallying cries sharpened last month when a New York man, whose case dragged on following an arrest on a minor parole violation, was infected inside Rikers Island jail and died. The top doctor at Rikers, Ross MacDonald, called the current situation “a crisis of a magnitude no generation living today has ever seen” and has asked that “the focus remain on releasing as many vulnerable people as possible.”

While much of the national discourse has focused on releasing those already behind bars, attorneys also are fighting for those like Madero who are poised to go behind bars in the weeks and months ahead.

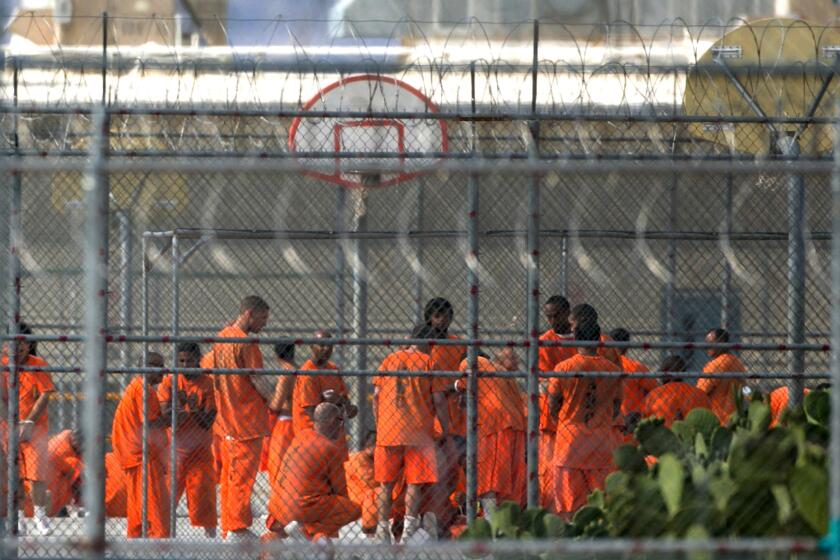

Across America, lockups, like nursing homes, are hot spots for the virus.

Coronavirus infections explode at a Lompoc federal prison with 792 testing positive, making it the largest federal penitentiary outbreak in the nation.

On Rikers Island, nearly 1,300 inmates and guards have contracted the coronavirus, and in Chicago about 800 at the Cook County Jail have tested positive. In Los Angeles County jails, inmates have described pandemic-era conditions as “slow torture,” including resorting to using torn bed sheets as toilet paper. More than 300 inmates in the jail system have been infected.

Moreover, such numbers, defense attorneys and activists believe, reflect a vast undercount, considering the limited testing, social distancing and sanitation.

Many of the best defenses for slowing the spread of virus — washing hands for 20 seconds, wiping down surfaces and standing several feet apart — aren’t possible for most inmates, said Lauren-Brooke Eisen, director of the Justice Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law.

“Those behind bars can’t engage in the steps we practice to quell the spread of COVID-19,” Eisen said.

In Arizona, which has the highest incarceration rate of Western states and the fifth-highest in the nation, roughly 70 inmates have contracted the virus, and the first confirmed case at the Maricopa County jail here in Phoenix came at the end of April.

It’s not uncommon here for people to serve long sentences for low-level drug crimes; possession of small amounts of marijuana for non-medicinal use remains a felony. Like most of the country, black and Latino men are disproportionately incarcerated.

Madero, who is Latino, and many people have seen the headlines of high-profile white men being released from detention centers early, such as Michael Avenatti, the attorney who was convicted of extortion in a case separate from the one in which he represented a porn star who said she had a pre-presidential affair with Donald Trump. Avenatti’s release last month from a New York correctional facility is temporary; he must eventually return.

For Madero, the looming incarceration day weighs on him.

After his release in 2018 after four years behind bars, Madero sought treatment for an addiction to methamphetamine and he has worked in restaurants and construction.

But, eventually, he relapsed.

Madero was cited last year for aggravated DUI — because even though he did not have alcohol in his system, he allegedly tested positive for trace amounts of meth. That was prior to the pandemic.

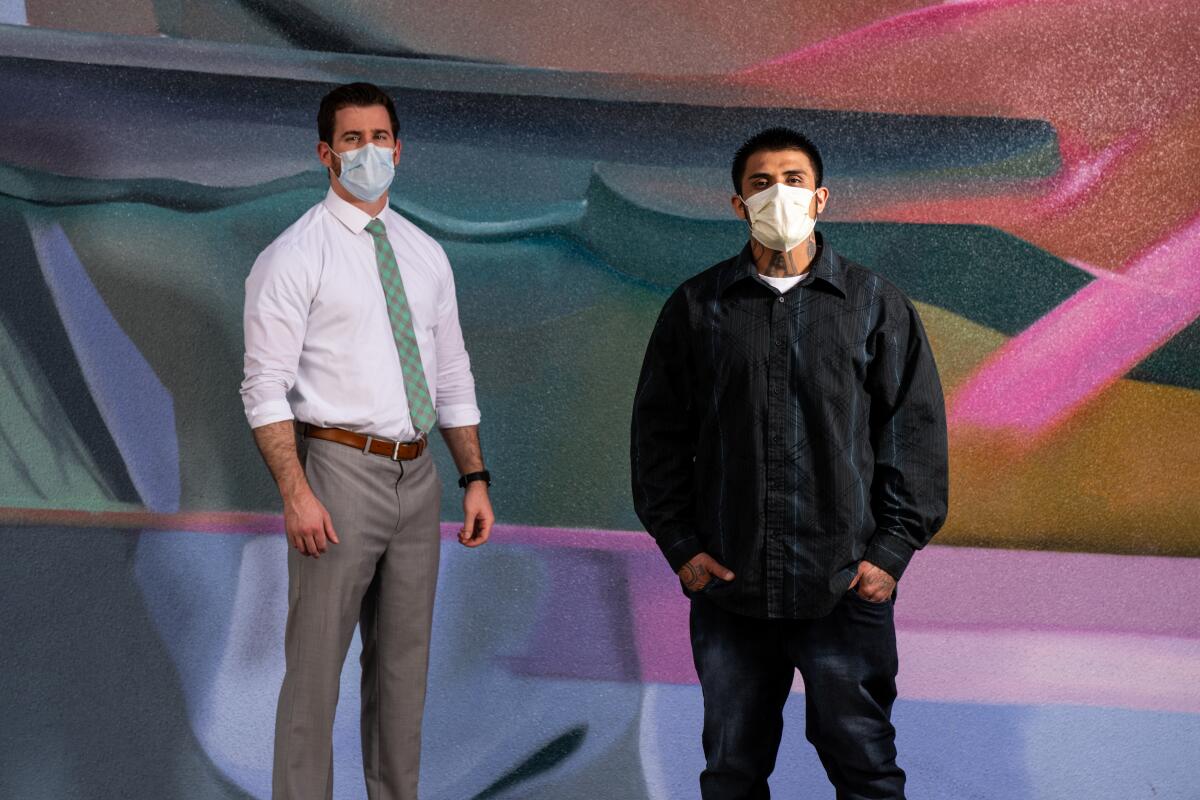

Madero’s attorney, Jack Litwak, now hopes for a delay or a reduced sentence.

The Phoenix attorney has suggested to the court that Madero needs treatment, not incarceration, and that he believes his client is on the losing end of criminal justice policies. A white woman with three DUI convictions and a history of violent assaults, he noted in a brief, was recently given a plea deal of six months compared with the six years offered to Madero. The longer Madero is behind bars, especially during the pandemic, the higher the risk of contracting the coronavirus, Litwak said.

“The conditions in the facilities are ripe for infection: They share showers and cells, have limited access to cleaning supplies, delays in medical care,” said the lawyer. “His family deserves to have him in a safe environment, where he can receive adequate treatment for his addiction.”

Each month, more than 1,100 people show up at Maricopa County jail to begin serving sentences. There are nearly 9,100 beds in the facility, but so far, only about 130 inmates have been tested for the coronavirus, according to officials.

Madero remembers the time he spent inside the Maricopa County jail before the pandemic. He can still visualize the dried-blood-stained uniform the guards made him wear for several days, the double bunks where he slept a few feet from another man and the limited amount of soap.

“Terrible, it was really terrible,” Madero said. “And just really scary.”

More states are freeing prisoners due to coronavirus, but Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey claims less drastic health measures are enough for its 42,000 inmates.

On average, cities nationwide have reduced jail populations by 25% since March, according to the Prison Policy Initiative, a national group dedicated to criminal justice reform. And a recent report from the Maricopa County sheriff showed that the inmate population, which stood at roughly 7,100 in January, has shrunk to near 5,500. Average daily bookings into the jail have declined by 100 per day, the report says, down from the more typical 300.

Khalil Rushdan, a community outreach coordinator for the ACLU of Arizona, has helped lead calls for reductions in jail populations. The ACLU is asking that nonviolent offenders across the nation who are older and have underlying health conditions be released.

“Prior to the pandemic, society as whole really did not care about mass incarceration. With the pandemic, I do think the issue has come to light much more,” Rushdan said. “We are talking about someone’s loved one possibly contracting this virus and dying because they were not allowed, as humans, to follow CDC guidelines of social distancing and consistent hand washing.

“Really, if we’re being honest, it’s a matter of life and death,” he said.

Defense attorneys have argued that, during the pandemic, it only makes sense to offer alternatives such as at-home monitoring with an ankle bracelet, or deferring incarceration start dates.

But such efforts face opposition from tough-on-crime politicians.

Former Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio, known for having created a notorious “tent city” that housed inmates outside in 100-degree weather and led to a raft of lawsuits, said it makes no sense to release inmates.

“Why do that? These people are safer on the inside. When they get out and go back to using drugs or whatever, they’re way more likely to get coronavirus,” Arpaio said on a recent afternoon, seated inside his home office in the suburbs.

Arpaio, who lost his position as sheriff in 2016, was granted a pardon by President Trump after being convicted of disobeying a federal judge’s order to stop racially profiling and detaining individuals suspected of being in the U.S. illegally. He is now running to reclaim the sheriff’s post.

“They will commit more crimes; they do harm, plain and simple,” Arpaio, 87, said of releasing inmates during the pandemic.

Madero said it isn’t that simple.

He hasn’t always been a model citizen, he acknowledges, and says he desperately wants to beat his addiction, but he doesn’t think incarceration is the best option.

He’s never been charged for a violent act, he said, and “every problem I have ever faced in my life so far was because of my drug addiction.”

These days, as he falls off to sleep, he thinks about who will tuck in his sons at bedtime. When they start school, who will walk them to and from the bus stop. What about his girlfriend? Who will support her?

He thinks about how he hopes to marry her one day, he says, and prays that he’ll get clean and remain sober. He also wonders whether, should he contract the virus while behind bars, he will prove healthy enough to survive.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.