Risking coronavirus cases to reopen: Can Europe save its summer travel season?

- Share via

Blanca del Rey sits in front of the stage where she danced for John Lennon until dawn, in the flamenco venue where her late husband once stopped Salvador Dali from entering with his pet ocelot.

Now all is dark as she waits for the tourists, for months barred by the pandemic, to return. Del Rey’s hopes of reviving her flamenco tablao — one of the most illustrious in Madrid — are entwined with the fate of European tourism, a $900-million industry in the fight of its life: to retrieve as much business as it can from the rest of the year.

“The only way we can reopen is when tourism returns to its normal levels,” says Del Rey’s son Armando, surveying the tiny stage, normally packed with musicians and dancers twice a night. “We have more than 70 staff and we mount the best productions we can. We [will] need close to 100% occupancy or we won’t make it.”

“We live thanks to foreign tourism,” says a masked Del Rey. “People often don’t value the beauty around them, so we need people from outside who can look at us with virgin eyes.”

Flamenco is a fundamental part of Spanish culture, but visitors from outside Spain account for 95% of receipts in the country’s estimated 100 tablaos. And in the Madrid of early summer 2020, there are almost no foreign tourists.

Whether, when and how they return is a massive issue for Madrid, for Spain and for Europe, the world’s No. 1 tourist destination.

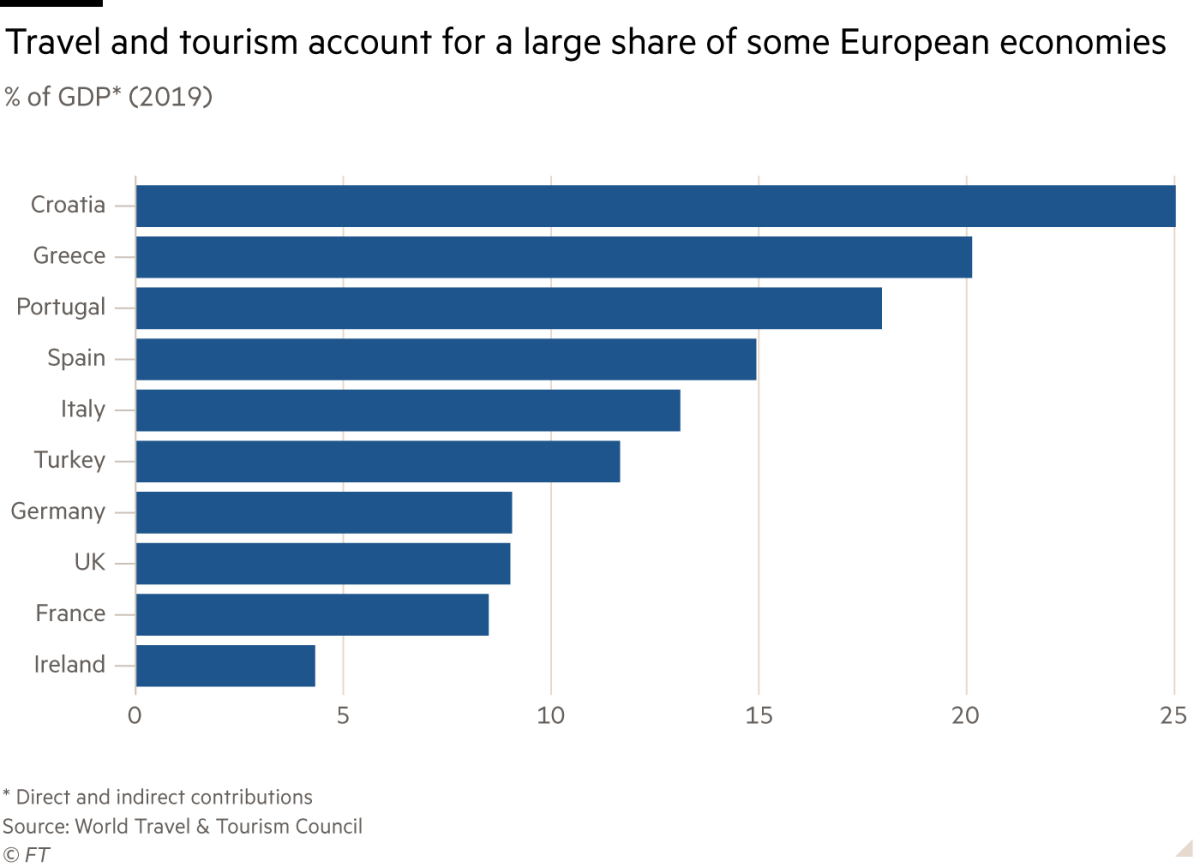

Tourism accounts for 12% of gross domestic product in Spain — perhaps the nation worst hit by the economic effects of the coronavirus crisis, which pushed the death rates up to among the highest in Europe and threatens to leave a fifth of people out of work until the end of 2021. As much as 10% of European economic activity depends on tourism, so the complete loss of this year’s season is a price no government can easily pay.

‘For the tourism industry itself, it’s worth risking a second wave just to get some revenue.’

— Tom Jenkins, European Tourism Assn. chief executive

There are two overarching questions: how much of the summer season can be salvaged, and will efforts to rescue it undermine the push to keep the pandemic under control? As they open up, countries may risk importing coronavirus cases from states with much higher levels of incidence.

“This is not a normal year. All we’re doing is looking at mitigation of losses,” says Tom Jenkins, chief executive of the European Tourism Assn., the trade body for travel companies across Europe. “For the tourism industry itself, it’s worth risking a second wave just to get some revenue.”

Reopening plans

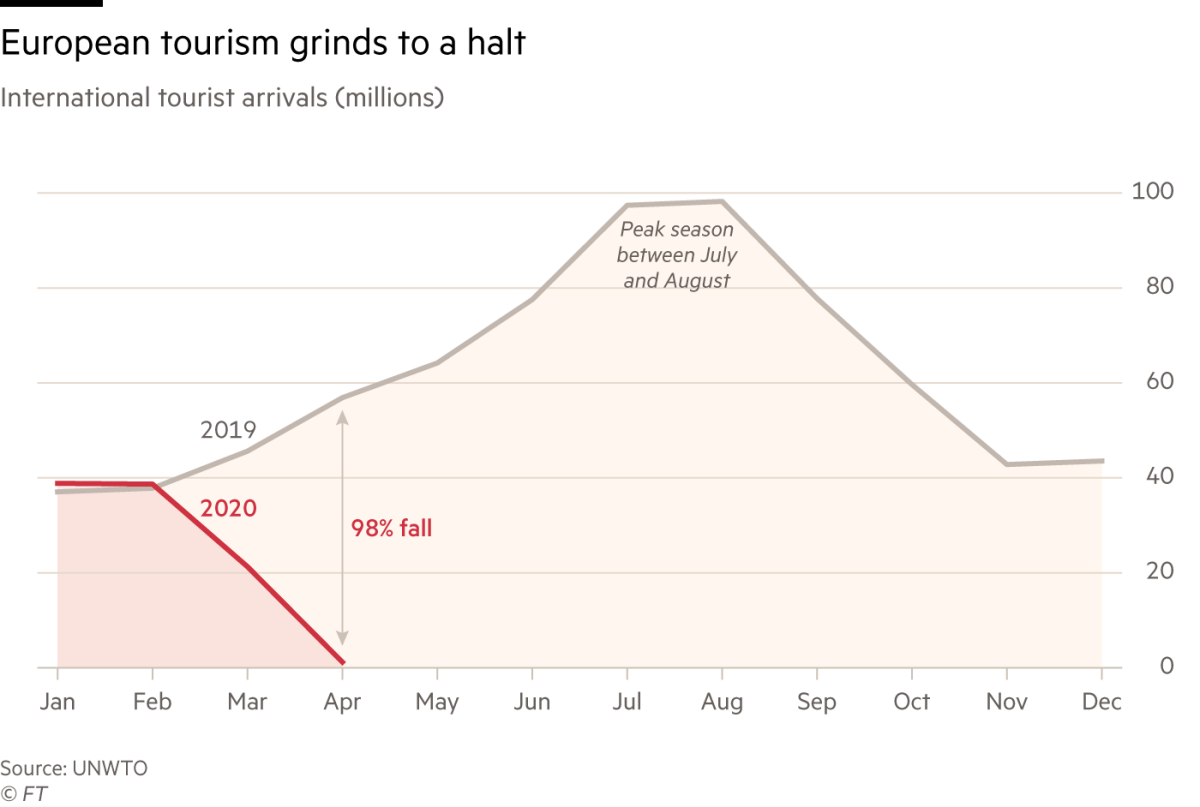

Governments and companies strongly reject the idea that they are risking people’s lives. But the industry is hurting badly, having already lost half of the peak season after coronavirus lockdowns wiped out the Easter and May holidays.

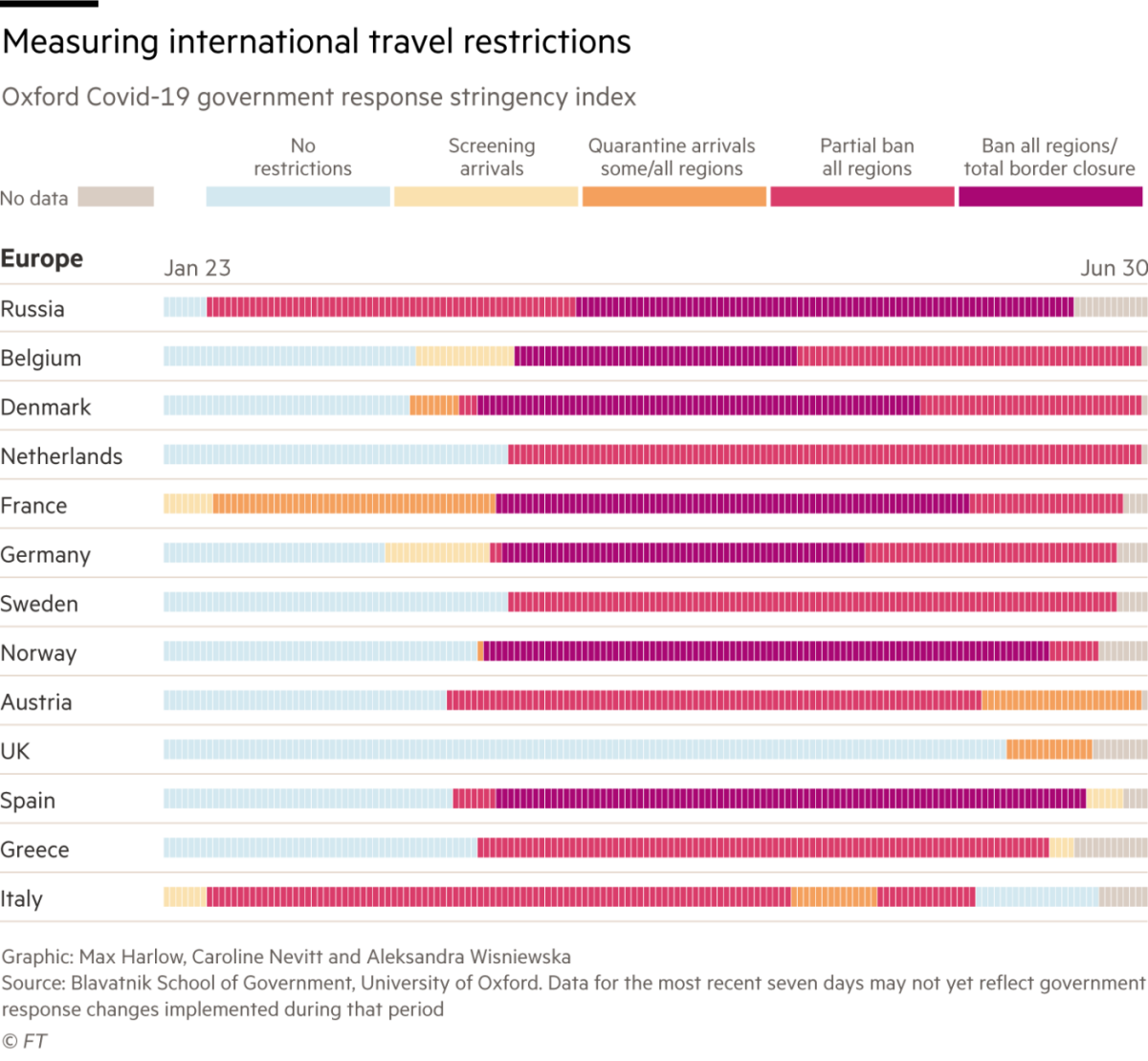

Countries are now reopening. On June 21, the day its harsh lockdown came to an end, Spain scrapped restrictions for the Schengen free travel zone and Britain. On Tuesday, the European Union agreed on a list of 15 countries that it recommends exempting from its coronavirus entry ban — although Italy is not implementing the list, retaining quarantine requirements from travelers outside Schengen.

The U.S. was not included on the list and Chinese visitors will only be allowed once there is reciprocal access for Europeans. Britain last week unveiled its own proposals for “air corridors” — routes to and from Britain for which 14-day quarantine rules will not apply.

All these moves are designed to bring tourism back from the dead and keep alive companies ranging from Corral de la Morería, Del Rey’s Michelin-starred flamenco venue, to airlines with incomes that normally reach into the hundreds of millions of euros.

Many groups are in desperate straits. Tui, Europe’s largest tour operator, has had to take on a $2-billion loan from the German government to make it through the crisis. Smaller businesses such as the British-based Specialist Leisure Group, which ran bus and river tours across Europe, have already gone into insolvency.

The collapse in tourism has also deepened the woes of the aviation sector, now enduring the worst year in its century-long existence. In April, global air travel plummeted 95% from 2019 levels. According to Iata, an industry trade body, every day this year airlines have lost an average of $230 million, taking the industry toward an expected year-end loss of more than $80 billion.

Carriers such as Ryanair, easyJet and British Airways are cutting thousands of jobs, the first steps in a restructuring that experts say is likely to lead to smaller airlines, serving fewer and less frequent routes.

Hence the urgency to reopen for business, with countries inviting tourists back almost as soon as internal travel restrictions came to an end. But governments are acutely aware of the challenge — and of the risks.

“This season is going to be very difficult for Spain and all the tourist [destination] countries,” says Isabel María Oliver, the Spanish state secretary for tourism. Acknowledging that long-haul tourists are unlikely to come in numbers this summer, she declines to give a target for this year — in 2019 the country welcomed 84 million visitors. “Our goal is to welcome foreign and domestic tourists safely — and for it to be safe for residents and industry workers as well.”

Safety is the priority

Around the Mediterranean coastline, hotels have doubled down on cleaning regimes that involve medical-grade hygiene products and wiping areas such as elevator buttons, reception desks and door handles, in some cases every two hours.

In Venice, authorities have been encouraging tourists to stay for longer and engage in “slow tourism”: rather than a frenetic tour around the city’s major sites, they are asking visitors to take more time and explore lesser-known areas.

Greek hotels now include plexiglass barriers at reception desks, sun-loungers placed at least 10 feet apart on the beach, and a ban on breakfast buffets.

“Safety is our overriding priority. We have to make sure tourists feel secure wherever they are in Greece so they can relax and enjoy themselves,” says Haris Theocharis, the country’s tourism minister. “This is a bigger concern for us than projections of numbers of arrivals.”

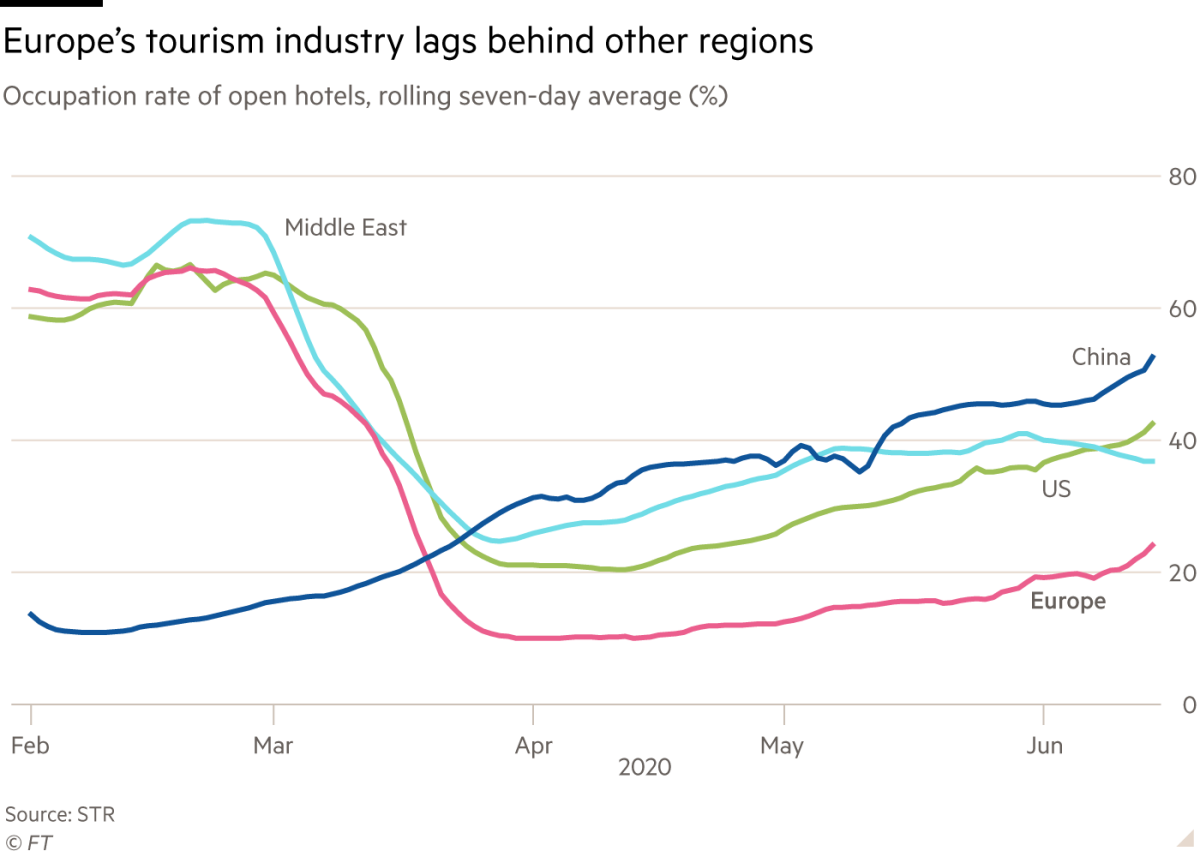

Indeed the early indications are that, although people’s appetite for travel is returning, it remains far below the levels of last year.

On Santorini, normally Greece’s most-visited island, 50% of hotels were still closed last Sunday. Direct flights from Germany are set to start Wednesday. Bookings for July are about 80% lower than last year, mainly due to the EU’s existing ban on travelers from the U.S., China and Russia, the island’s three most important markets, according to Antonis Iliopoulos, president of the Santorini hoteliers’ association.

“This season isn’t about making a profit,” he adds, “it’s about protecting our brand.”

Some in the industry remain relatively optimistic. “There is so much demand [that] prices explode,” says Friedrich Joussen, Tui’s chief executive, who points to jumps in bookings for locations such as Majorca and Portugal, which staged limited reopenings in June. “We started with [booking] vacations overland in Germany at the beginning of June around the islands in the North Sea, and what we saw was more or less 24 hours later we were booked.”

He acknowledges that Tui, which reported earnings of $1 billion on turnover of $21.3 billion last year, will achieve around half of what it makes in a normal year. Usually the group’s summer offerings are 70% booked at this time of year, but at present it is not even half that figure.

Many airlines remain cautious. Ryanair plans to operate about 40% of its flight capacity in July, before increasing it to about 60% to 70% by September. EasyJet, Europe’s other leading low-cost carrier, plans to fly about 30% of its normal capacity until September. It believes passenger demand will not return to 2019 levels until at least 2023.

Prices are also being crunched. The British-based price comparison website TravelSupermarket has reported falls of between 22% and 37% for southern European package holidays since the lockdown began, while noting a 52% increase in bookings for such vacations last week after the government outlined plans to ease the lockdown, compared to two weeks earlier.

Reimporting the virus

Many countries have launched drives to encourage people to vacation at home. But in Mediterranean countries such as Italy, Spain and France, such domestic tourism can hardly substitute for international demand and will rarely include the big-ticket items, such as high-end hotels, beloved by some foreigners. With the U.S. absent from the EU’s list of approved countries for travel, the American tourists who help bankroll Madrid’s flamenco tablaos are, for now, out of the picture.

Axel Hefer, chief executive of the online travel company Trivago, says Germany — which has not suffered as much as other countries from the pandemic — is now Europe’s biggest driver of tourist demand. But among German consumers, car vacations are more popular than any involving a flight.

Having been told to stay at home for more than three months, many potential tourists are deterred by the idea of flying out of their own countries and sharing facilities with others when there is still no coronavirus vaccine or treatment.

“You have to accept an element of risk, coming to Greece at a time like this,” says Michael Schmidt, a software engineer from Austria strolling through Plaka, an Athens neighborhood of shops and cafes. “But I’m surprised — given its good record on keeping down the virus — that so few people [both locals and tourists] are wearing masks and so many are not observing social distancing.”

Despite fears of reimporting the virus, the Spanish government has decided unilaterally to waive restrictions for travelers from Britain, even though Spain reports far fewer infections — below 300 a day, compared with more than 800 in Britain.

Greece faces an even starker dilemma: it has contained the spread of the coronavirus so successfully that fewer than 20 cases in total have been reported on the Aegean Islands, the country’s main hub for tourism. To assuage islanders’ fears that tourists infected with the virus will cause outbreaks in places that have so far escaped COVID-19, the government has rented hotels to serve as quarantine centers and hired 200 extra doctors.

Nikos Hardalias, deputy minister for civil protection, says a network of fast coast guard boats and a helicopter service will be able to ferry COVID-19 patients to an intensive care unit from any island in less than three hours. In a sign of possible concern, however, Greece on Monday delayed the opening of tourist flights from Britain until mid-July.

The resurgence of the pandemic in the U.S. highlights the risk of returning to economic activity too quickly.

In a recent interview, Salvador Illa, Spain’s health minister, said Madrid hoped to use improved testing and targeted restrictions to deal with inevitable new outbreaks, but acknowledged he could not rule out another general shutdown.

That would be the nightmare scenario for the European tourism sector and the region as a whole. Many international forecasts list two sets of projections for this year and next: a record contraction if there is no second wave, and an even grimmer outlook if there is.

“More than the fear that the tourists might have,” says Armando del Rey at Corral de Morería, “it is the uncertainty that makes things so hard to manage.”

Even as pressure builds to open up again, governments and companies are conscious that health risks taken for the sake of business could sink the economy and, most of all, the tourism sector. It is significant that EU member states have backed only the relatively limited list of 15 countries for resumed travel, despite the hit that represents for the tourist industry.

Some industry figures consider that ultimately the sector may be able to pull in half of 2019’s receipts this year, but that still implies a loss of hundreds of billions of euros across Europe. That’s the view of José Luis Yzuel, head of Hostelería de España, an organization that represents more than 270,000 bars and restaurants. He thinks there may be a limited return to Spain’s coasts and islands but not much more than that.

“This season is gone,” Yzuel says. “If the tourism industry can recover 50% of last year’s sales, that will be a triumph. But then if you compare something with complete annihilation, anything looks good.”

Daniel Dombey reported from Madrid, Alice Hancock and Tanya Powley from London, and Kerin Hope from Athens.

© The Financial Times Ltd. 2020. All rights reserved. FT and Financial Times are trademarks of the Financial Times Ltd. Not to be redistributed, copied or modified in any way.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.