Texas resumes executions after 5-month delay because of pandemic

- Share via

HUNTSVILLE, Texas — A Texas inmate was killed by lethal injection Wednesday evening for fatally shooting an 82-year-old man nearly three decades ago, ending a five-month delay of executions in the nation’s busiest death penalty state because of the coronavirus pandemic.

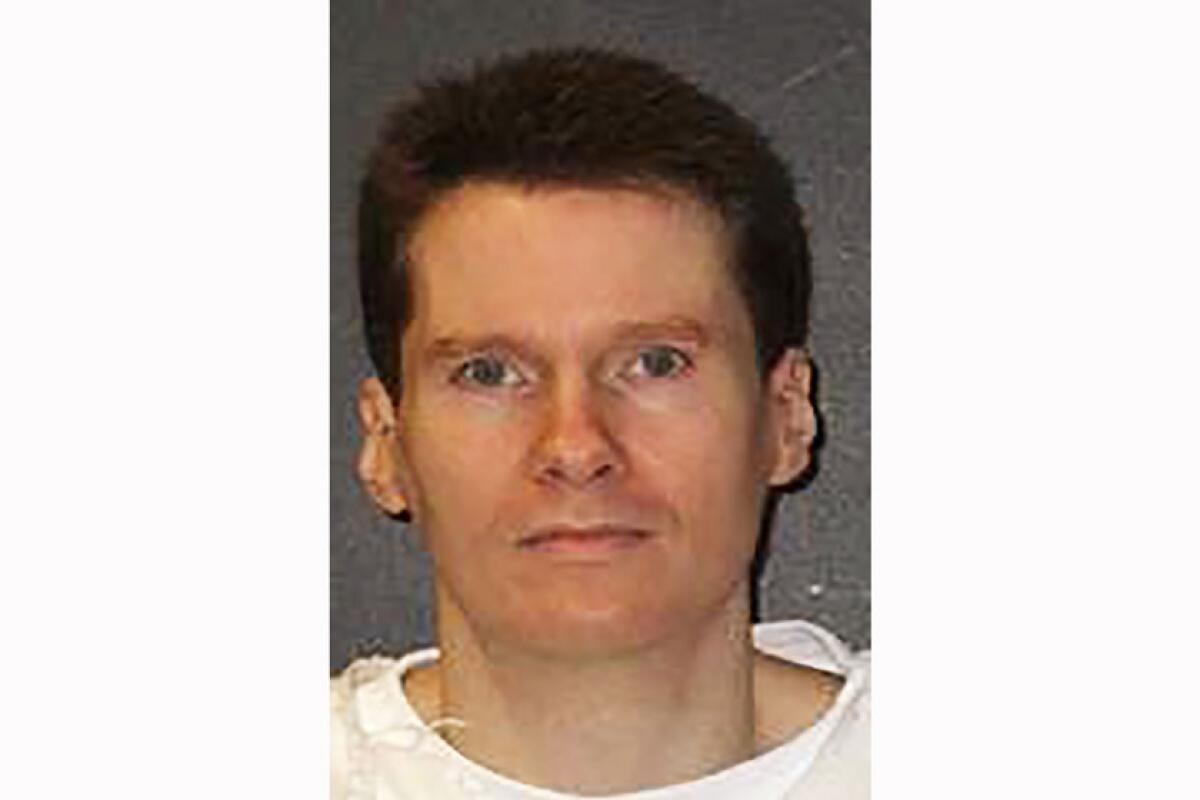

Billy Joe Wardlow was put to death at the state penitentiary in Huntsville for the June 1993 killing of Carl Cole at his home in Cason, about 130 miles east of Dallas in the east Texas piney woods, near the Louisiana and Arkansas borders.

The U.S. Supreme Court declined to stop the 45-year-old man’s execution.

Wardlow was the first inmate in Texas to be put to death since Feb. 6 and the second in the U.S. since the nation began reopening following pandemic-related shutdowns.

Strapped to the death chamber gurney, Wardlow declined to make a final statement when asked by the warden. He did nod and smile broadly, mouthing words to several friends who watched through a window from an adjacent witness room.

As the lethal dose of the powerful sedative pentobarbital was administered, he took three deep breaths, snored twice and then took a couple shallow breaths before stopping all movement. He was pronounced dead 24 minutes later, at 6:52 p.m. Central time.

A judge had moved Wardlow’s execution date from April 29 to Wednesday after Morris County Dist. Atty. Steve Cowan requested the change, citing the statewide disaster declaration due to the virus.

In Texas, the number of confirmed COVID-19 virus cases and hospitalizations has risen in recent weeks. But state prison officials say safety measures they’ve put in place will help executions to go forward. Execution witnesses on Wednesday were given masks and gloves. All prison officers and officials wore masks. Wardlow did not have one.

Six executions scheduled in Texas for earlier this year were postponed by the courts because of the outbreak. Two others were delayed over different issues.

Wardlow was 18 at the time of the slaying, and his attorneys have argued that one of the issues Texas jurors have to determine before imposing a death sentence — whether a defendant will be a future danger — can’t be reliably made for people younger than 21 because scientific research has shown their brains are still developing. Wardlow’s attorneys have asked the U.S. Supreme Court to stop his execution, saying he committed a “poorly-thought-out and naively-motivated robbery” to steal a truck so he could run away with his girlfriend.

“The science really supports precluding the death penalty for anyone under 21 because brain development is still happening,” said Richard Burr, one of Wardlow’s attorneys.

Prosecutors argued there was no constitutional error when the jury considered the issue of future dangerousness, and society has long used the age of 18 as the point where it draws the line for many distinctions between childhood and adulthood.

“Wardlow senselessly executed elderly Carl Cole to steal his truck, something that could have been taken without violence because the keys were in it,” the Texas attorney general’s office said in a petition filed with the Supreme Court.

The court also denied petitions from Wardlow over claims of ineffective assistance of counsel and related to the dismissal of a previous appeal in state and federal court. On Monday, the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles turned down his clemency petition.

Wardlow’s petition on brain development had its roots in a 2005 decision in which the Supreme Court banned the execution of offenders younger than 18 when they commit crimes. The Supreme Court pointed to research showing that character and personality traits of juveniles are not fully formed like adults.

Since that ruling, scientific research has established that the brains of those between the ages of 18 and 20 are functionally indistinguishable from someone who is 17, making their executions a violation of the constitutional protection from cruel and unusual punishment, Burr said.

In a clemency petition to the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles, Burr argued that as Wardlow grew older on death row, “kindness and compassion have been his defining characteristics.” Two jurors who condemned Wardlow had asked the board to commute his sentence to life without parole.

A group of academics and professionals in neuroscience and brain imaging had also asked the Supreme Court to stop the execution, saying the prediction of Wardlow’s future dangerousness “was scientifically unfounded when made and refuted by his character today.”

But the attorney general’s office pointed out that Wardlow had previously threatened to shoot an officer and threatened jail staff and other inmates after his arrest. They also noted that in his written confession, Wardlow said Cole “was shot like an executioner would have done it.”

Wardlow was the third inmate put to death this year in Texas and the seventh in the U.S.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.