Judge halts federal execution of prisoner said to be mentally ill

- Share via

TERRE HAUTE, Ind. — A judge Wednesday halted the execution of a man who was to be the second person put to death by the federal government after a 17-year hiatus but who lawyers said was suffering from dementia.

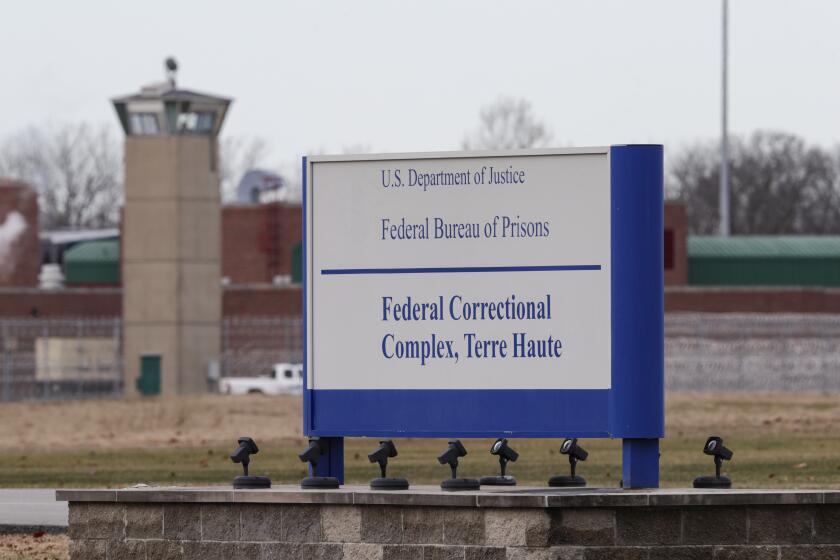

Wesley Ira Purkey, convicted of a gruesome 1998 kidnapping and killing, was scheduled for execution Wednesday at the U.S. Penitentiary in Terre Haute, Ind., where Daniel Lewis Lee was put to death Tuesday after his last-ditch legal bids failed.

U.S. District Judge Tanya Chutkan in Washington imposed two injunctions Wednesday prohibiting the federal Bureau of Prisons from moving forward with Purkey’s execution by lethal injection. The Justice Department immediately appealed in both cases. A separate temporary stay was already in place from the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

The early-morning legal wrangling suggests a volley of litigation will continue in the hours ahead of Purkey’s scheduled execution, similar to what happened when the government executed Lee following a ruling from the Supreme Court.

Lee, convicted of killing an Arkansas family in a 1990s plot to build a whites-only nation, was the first of four condemned men scheduled to die in July and August despite the coronavirus outbreak raging inside and outside prisons.

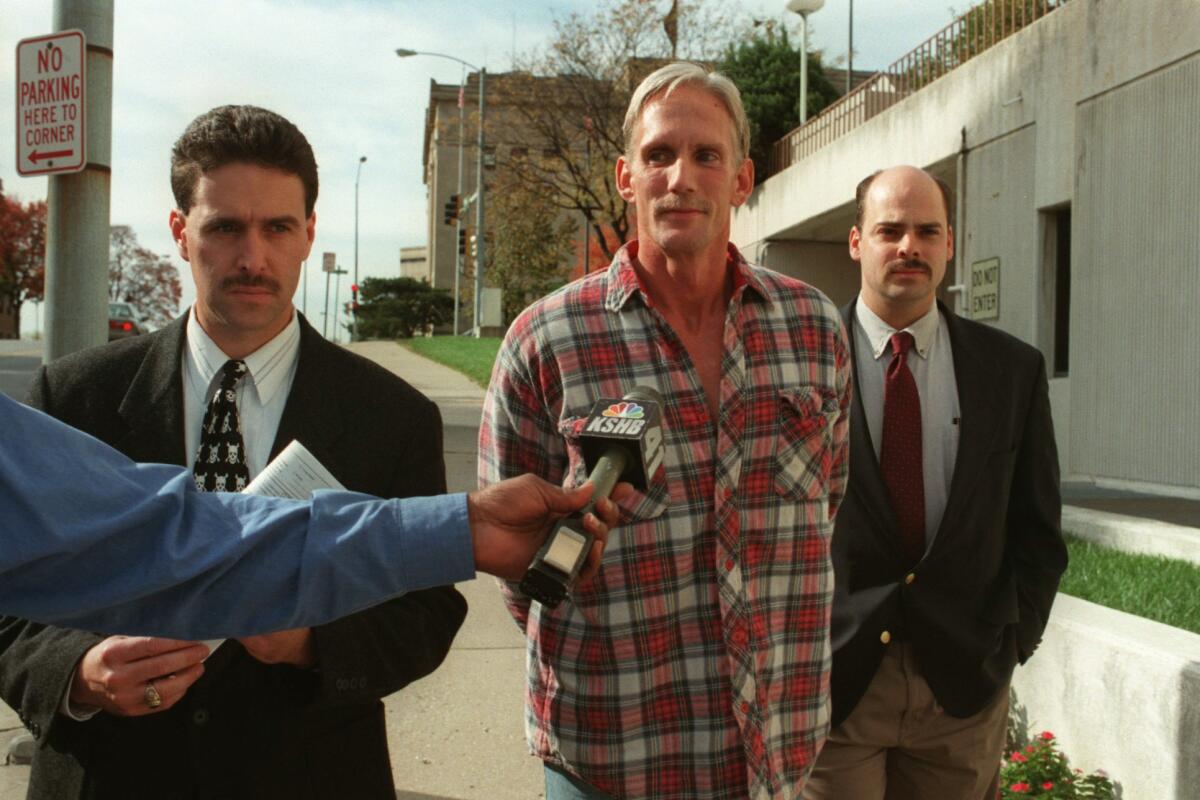

Purkey, 68, of Lansing, Kan., was to be the second. His lawyers are expected to press for a ruling from the Supreme Court on his competency.

“This competency issue is a very strong issue on paper,” said Robert Dunham, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center. “The Supreme Court has halted executions on this issue in the past. At a minimum, the question of whether Purkey dies is going to go down to the last minute.”

William Barr’s rush to resume federal executions flouts justice, and the Supreme Court just enabled it.

Chutkan didn’t rule on whether Purkey was competent but said the court needed to evaluate the claim. She said that although the government might disagree with Purkey’s lawyers about his competency, there was no question he’d suffer “irreparable harm” if he were to be put to death before his claims could be evaluated.

Lee’s execution Tuesday went forward a day late. It was scheduled for Monday afternoon, but the Supreme Court only gave the green light in a narrow 5-4 ruling early Tuesday.

Repeatedly on Wednesday, a federal judge also denied a request from Dustin Lee Honkin, an Iowa drug kingpin scheduled to be executed on Friday, to delay his execution. The judge said he would not delay Honken’s execution date due to the coronavirus pandemic and said the Bureau of Prisons was in the best position to weigh the health risks.

The issue of Purkey’s mental health arose in the lead-up to his 2003 trial and also when, after the verdict, jurors had to decide whether he deserved to die for the killing of 16-year-old Jennifer Long in Kansas City, Mo. Prosecutors said he raped and stabbed her, dismembered her with a chainsaw, burned her and dumped her ashes 200 miles away in a septic pond in Kansas.

Purkey was separately convicted and sentenced to life in the beating death of 80-year-old Mary Ruth Bales, of Kansas City, Kan.

But the legal questions of whether he was mentally fit to stand trial or to be sentenced to die are different from the question of whether he’s mentally fit enough now to be put to death. Purkey’s lawyers argue that he clearly isn’t, saying in recent filings that he suffers from advancing Alzheimer’s disease.

Prop. 66’s failure to speed up California executions is more proof that we must end the barbaric practice. It is immoral, and it just doesn’t work.

“He has long accepted responsibility for the crime that put him on death row,” one of his lawyers, Rebecca Woodman, said. “But as his dementia has progressed, he no longer has a rational understanding of why the government plans to execute him.”

Purkey believes his planned execution is part of a conspiracy involving his attorneys, Woodman said. In other filings, they describe his delusions of people spraying poison into his room and of drug dealers implanting a device in his chest meant to kill him.

While various legal issues in Purkey’s case have been hashed, rehashed and settled by courts over nearly two decades, the issue of mental fitness for execution can only be addressed once a date is set, according to Dunham, who teaches law school courses on capital punishment. A date was set only last year.

“Competency is something that is always in flux,” so judges can only assess it in the weeks or days before a firm execution date, he said.

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

In a landmark 1986 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution prohibited executing someone who lacked a reasonable understanding of why he was being executed. It involved the case of Alvin Ford, who was convicted of murder but whose mental health deteriorated behind bars to the point that, according to his lawyer, he believed he was the pope.

Legal standards as to whether someone has a rational understanding of why an execution is taking place can be complex, Dunham explained.

“I could say I was Napoleon,” he said. “But if I say I understand that Napoleon was sentenced to death for a crime and is being executed for it — that could allow the execution to go ahead.”

Purkey’s mental issues go beyond Alzheimer’s, his lawyers have said. They said he was subject to sexual and mental abuse as a child and, at 14, was diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression and psychosis.

A blind prisoner convicted of killing his estranged girlfriend by setting her on fire in her car was put to death Thursday in Tennessee’s electric chair, becoming only the second inmate without sight to be executed in the U.S. since the reinstatement of the nation’s death penalty in 1976.

Last week, three mental health organizations urged U.S. Atty. Gen. William Barr to stop Purkey’s execution and commute his sentence to life in prison without possibility of parole. The National Alliance on Mental Illness, Mental Health America and the Treatment Advocacy Center said executing mentally ailing people such as Purkey “constitutes cruel and unusual punishment and does not comport with ‘evolving standards of decency.’”

The mother of the slain teenager, Glenda Lamont, told the Kansas City Star last year that she planned to attend Purkey’s execution.

“I don’t want to say that I’m happy,” Lamont said. “At the same time, he is a crazy madman that doesn’t deserve, in my opinion, to be breathing anymore.”

President Trump’s campaign touted the Lee execution in an email blast, saying the president “Ensured Total Justice for the Victims of an Evil Killer” and demanded his political opponent Joe Biden explain why he now opposed capital punishment.

Prior to Lee’s execution Tuesday, the government had put to death only three defendants since restoring the federal death penalty in 1988. Before Lee, the most recent execution occurred in 2003, when Louis Jones was executed for the 1995 kidnapping, rape and murder of a young female soldier.

In 2014, after a botched state execution in Oklahoma, President Obama directed the Justice Department to conduct a broad review of capital punishment and issues surrounding lethal injection drugs.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.