Trump administration clears way for Alaska’s Pebble Mine, despite fears it could imperil a salmon fishery

- Share via

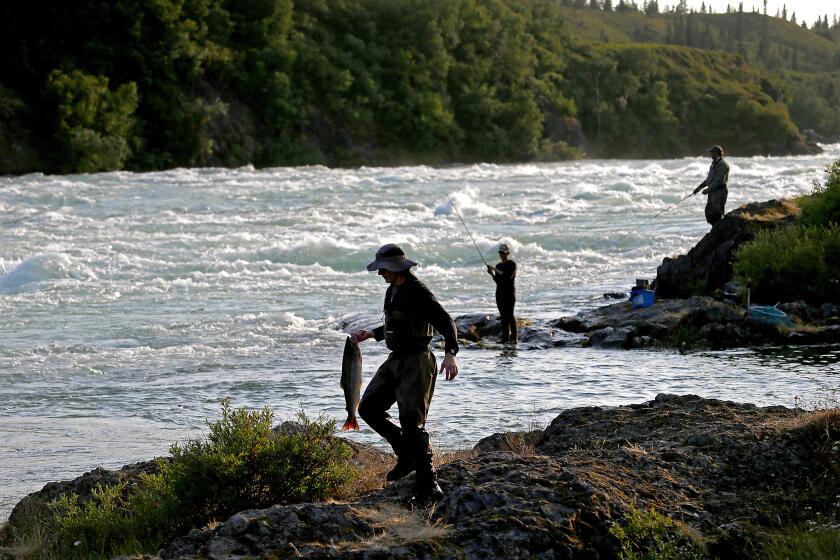

SEATTLE — The Trump administration has lifted a major hurdle for development of a massive gold and copper mine in the wilds of Alaska despite fears that it will poison the world’s largest sockeye salmon run.

Pebble Mine, which would become an open pit the size of 460 football fields at the headwaters of Bristol Bay, has long been opposed by environmentalists and the commercial fishing industry.

But in a final environmental impact statement released Friday, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers concluded that the mine “would not be expected to have a measurable effect on fish numbers” or “result in long-term changes to the health of the commercial fisheries.”

That clears the way for the Corps to issue a permit this year to Northern Dynasty Minerals Ltd., the Canadian company proposing the mine on state land.

The company must also secure numerous state permits, and opposition from Native entities and other groups could tie up the project in court battles. It is also possible that the federal government could reverse course if Trump loses the presidency this fall.

Still, the new report is a setback for the project’s opponents, who accuse the Trump administration of politicizing a review process as part of a broader national campaign to roll back decades of environmental protections.

A giant open-pit copper and gold dig above Alaska’s Bristol Bay could yield sales of more than $20 billion in two decades, but Pebble Mine would place the world’s greatest wild salmon run at risk forever.

“The Army Corps’ conclusion that all of this will have ‘no measurable effect’ on Bristol Bay’s salmon fishery would be laughable if it weren’t so disturbing,” said Taryn Kiekow Heimer, a Natural Resources Defense Council senior advocate. “The Trump administration just ran roughshod over the input it received from its own agencies, independent scientists, Bristol Bay tribes and commercial fishermen.”

In Alaska, a strongly pro-development state, Pebble Mine is deeply unpopular, with 62% of voters in a recent poll opposing it — mainly because of fears that it would harm the $1.5-billion Bristol Bay salmon fishery, which supports 14,500 jobs.

“For the Army Corps to rubber-stamp a massive, toxic open-pit mine in the headwaters of a national food source just doesn’t make sense,” said Andy Wink, executive director of the Bristol Bay Regional Seafood Development Assn. “What the Pebble Partnership has proposed is essentially one big experiment with no real science or data to back it up.”

But Tom Collier, chief executive of Pebble Limited Partnership, the U.S. subsidiary of Northern Dynasty, said Friday that the Corps’ process was “extensive, rigorous and transparent,” and not in fact rushed, taking more than two years, which he said was about average for environmental reviews in Alaska.

“Unequivocally, repeatedly, the document concludes, as the draft did, that we’re not going to do any damage to this fishery, period,” Collier said. “We changed the project to address environmentalists’ concerns, and the project we took into permitting had been ‘de-risked.’”

In a scientific review conducted under the Obama administration, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency found that the mine could result in “significant and unacceptable adverse effects” on fishery areas and ecologically important streams, wetlands, lakes and ponds.

Under the current proposal, development of the mine would destroy more than 2,000 acres of wetlands and more than 100 miles of streams.

Tailings from the mine would be heaped across 2,800 acres behind dams extending more than 10 miles. In a region that averages 50 inches of rain a year, the challenge would be to ensure that tainted water never reached Bristol Bay.

The mine could generate up to $1 billion a year in sales of gold, copper, molybdenum and other commodities. Once permits are secured, industry experts expect North Dynasty to sell the claim to a larger mining company.

One controversial element of the project was a plan to use ice-breaking ferries to haul ore 18 miles across Iliamna Lake — before trucking it an additional 37 miles on a new road through bear habitat to a port to be built at Cook Inlet.

The opponents of that plan included environmentalists, who said ferries would disturb a colony of freshwater seals, as well as Native villages, whose residents drive across the ice during winter for supplies.

Apparently heeding those concerns, the new assessment by the Corps instead backs an 82-mile road north of Iliamna Lake to a different port site as the “least environmentally damaging practicable alternative.”

The two-lane road, with 17 bridges, would be flanked by a pipeline that would bring natural gas from across Cook Inlet for a 270-megawatt power plant at the mine.

But that route presents another challenge. Three Native corporations own rights to the land, and they say it’s not for sale.

“Their insistence on pushing this impractical route forward, which is reliant on lands not open to Pebble development, disrespectfully ignores our tribal sovereignty,” the Igiugig Village Council said in a statement Friday.

Collier said Friday that it was not unusual for projects to receive permits despite outstanding property issues.

“Now we’re in a situation that it’s incumbent on us to convince these landowners that they should in fact cooperate with the project and allow the northern route,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.