Righting a wrong — and rewriting a racist legacy

- Share via

CHICAGO — Law professor Steven Drizin had seen it again and again, and it pained him: Prosecutors wielding a decades-old legal case to justify a juvenile’s confession to a serious crime. Illinois vs. Hester, as a colleague put it, also “smelled bad.”

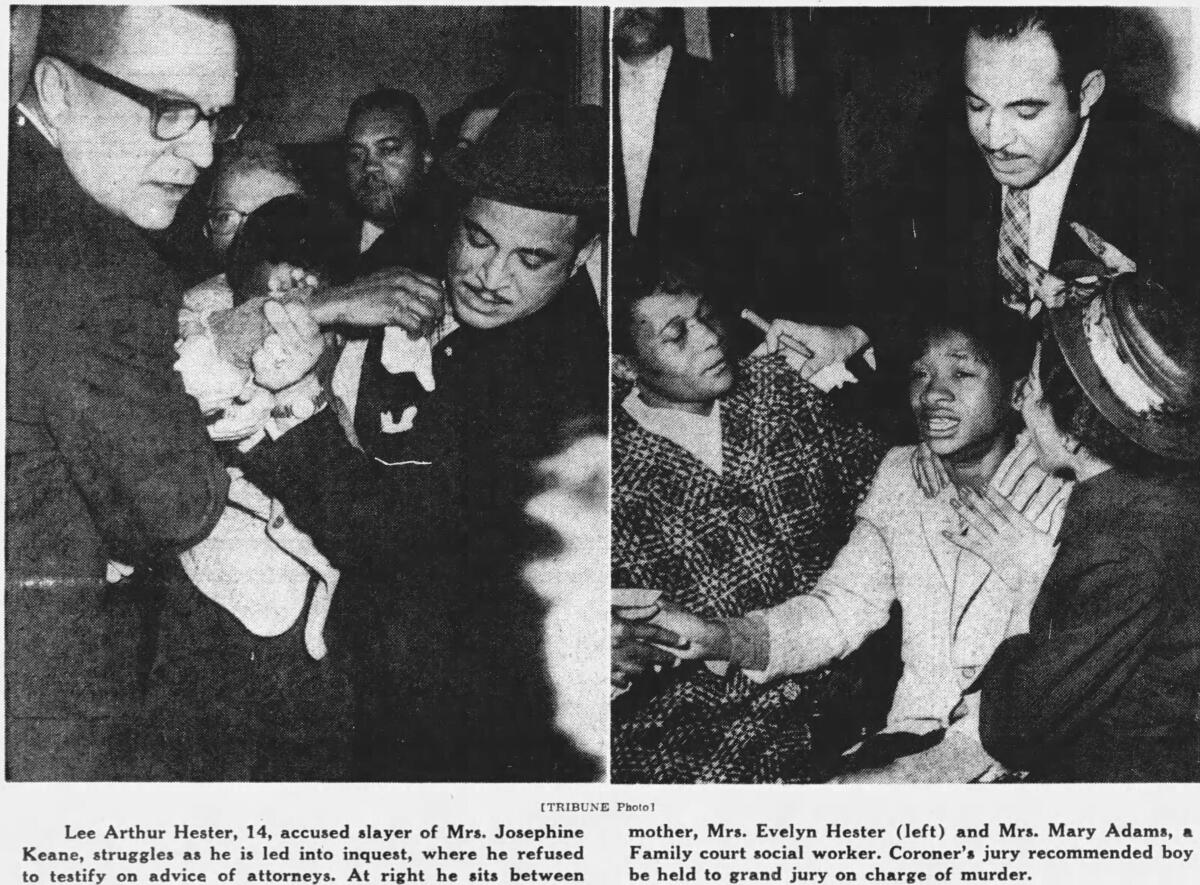

It seemed probable that Lee Arthur Hester, the case’s Black 14-year-old defendant, had falsely confessed to fatally stabbing a white teacher. As they dug into the 1961 conviction, Drizin and colleagues at Northwestern University became convinced Hester had been railroaded by racist authorities, an injustice that controlled the fate of many boys and girls in the years to come.

Clearing Hester’s name would not be easy. Evidence had vanished. Key witnesses had died.

Also, this case wasn’t about freeing Hester from prison. He was paroled in 1972, meaning there would be no public pressure to save a man from death row. But in the face of such an obvious wrong, they thought they had to try.

“There is no expiration date on justice. It’s not like a carton of milk,” Drizin said. “So many false confessions were taken from young African American boys and men in this city. It’s not just a problem that started in the 1970s, 1980s or 1990s. There is a long, long history here. And Lee Arthur’s case was an important part of that history.”

Drizin, 59, is co-director of Northwestern University Law School’s Center on Wrongful Convictions and looks and acts every bit the law professor — he wears spectacles, has gray receding hair and speaks in careful, complete paragraphs.

The professor has helped exonerate at least 20 men and women convicted of serious crimes; he specializes in unwinding false confessions by juveniles, especially those by African Americans in Chicago who were victims of racist police practices.

Drizin decided to look into the Hester case in 2010 after discussing it with a Northwestern colleague, Thomas F. Geraghty, who had long doubted police arrested the right suspect. Working out of his cluttered office overlooking Lake Michigan, Drizin began exploring the case’s history.

Hester had been quickly arrested in the April 20, 1961, stabbing and rape of one of his favorite teachers, 45-year-old Josephine Keane, in a storage room at their school, Lewis-Champlin, on this city’s South Side.

In just a few decades, Lewis-Champlin had gone from a nearly all-white to all-Black student body, mirroring seismic demographic changes across Chicago. The killing touched a nerve, particularly among whites anxious about Blacks moving into their neighborhoods.

The slaying and arrest were intensely covered by Chicago’s newspapers and radio stations. The Chicago Tribune ran a story about Hester’s arrest on the front page, next to articles about the failed Bay of Pigs invasion and a speed record set by the X-15 jet. The city’s other newspapers published a photo of Keane’s corpse in a body bag and an article about how teachers “had been fearful for some time of a growing danger a number of them face in schools in certain areas of the city.”

Tensions did not die down. Not six months after Hester’s arrest, Black and white spectators packed shoulder to shoulder in a Chicago courtroom to witness the trial. “It was impossible to ignore the rank overtones of racism” among whites convinced of Hester’s guilt, reported the Chicago Defender, a Black-run newspaper.

As Drizin combed newspaper archives, the professor was struck by how Hester was portrayed in the media. Photos revealed a boy so slight his clothes hung on him like he was a coat hanger. Even so, a newspaper described him as a bully and “strong as an ox.”

Hester was convicted after a two-week trial — the jury had one Black member and 11 whites — and sentenced to 55 years in prison. The youth lost his appeals. In an unexpected twist, Drizin discovered Hester’s lawyers argued before the Supreme Court that the youth’s confession should have been suppressed and his conviction overturned. For reasons lost to history, the justices declined to issue a ruling. (Under a 2017 Illinois law, police can no longer question someone in Hester’s circumstances without a lawyer present.)

Drizin met Hester through Jerome Feldman, a lawyer who defended the boy in 1961. Feldman, who has since died, told Drizin he had never wavered in believing Hester was innocent and they had become lifelong friends.

A gospel singer who did odd jobs for a living, Hester reaffirmed his innocence and explained he had not allowed the conviction to derail his life. Paroled early for good behavior, Hester had kept his conviction secret from his own children. Now 73, he declined to comment for this story.

Hester agreed to allow Drizin and his Northwestern colleagues — including Laura Nirider, the 38-year-old co-director of the wrongful conviction center — to wage a legal battle to clear his name.

(Drizin and Nirider would attain some fame for their unsuccessful effort to toss the conviction of Brendan Dassey, who at 16 confessed to a participating in the rape and killing of Teresa Halbach in 2005, a crime featured in the hit Netflix documentary “Making a Murderer.”)

Drizin and Nirider soon obtained reports that revealed how Hester had come under the police microscope. Investigators were convinced a Black student was responsible, and detectives, including one who was later convicted of drug trafficking, zeroed in on Hester. The boy was an easy target — a fifth-grader with below-average intelligence who white teachers reported had behavioral problems.

Detectives noticed Hester had what they thought was a lipstick smudge on his collar and a blood spot on his trousers. He was taken to a juvenile detention center to be questioned, without a lawyer or parent in the room.

Hester at first maintained his innocence. But police were relentless. They lied about the crime scene, about the evidence, about allowing Hester to go home to his mother if he just confessed, the boy testified. After hours spent alone in what Hester called a “dark dungeon room,” he admitted he had killed and sexually assaulted Keane.

The confession made no sense to the Northwestern professors. The boy claimed he stabbed Keane in the back by accident after tripping over some books. He stumbled again and struck her a second time in the back; the teacher actually was stabbed in the chest and right side. Hester’s description of the sexual assault did not correspond to evidence collected from the scene.

The professors were puzzled by how police could believe that a boy, 6 inches shorter and 35 pounds lighter than Keane, overpowered the teacher, stabbed her, raped her and calmly returned to class, with no one the wiser.

In their research, Nirider and Drizin even uncovered a better suspect — a white engineer at the school who had a history of institutionalization and was sent to a mental health facility after Hester’s arrest. They obtained government reports that further revealed the engineer was a violent paranoid schizophrenic. The man had beaten his wife and children and was reported to be a religious fanatic obsessed with sex.

The Northwestern team sought to have the conviction thrown out, but prosecutors fought their efforts. In 2015, a judge denied the lawyers’ request, ruling their arguments were based on nothing more than “speculation, rumor and sympathy.”

Prospects for Hester seemed dim until the next year when Kim Foxx, a political progressive, won election to become Cook County’s top local prosecutor. One of her first actions was to beef up a unit tasked with reviewing problematic prosecutions and throwing out wrongful convictions.

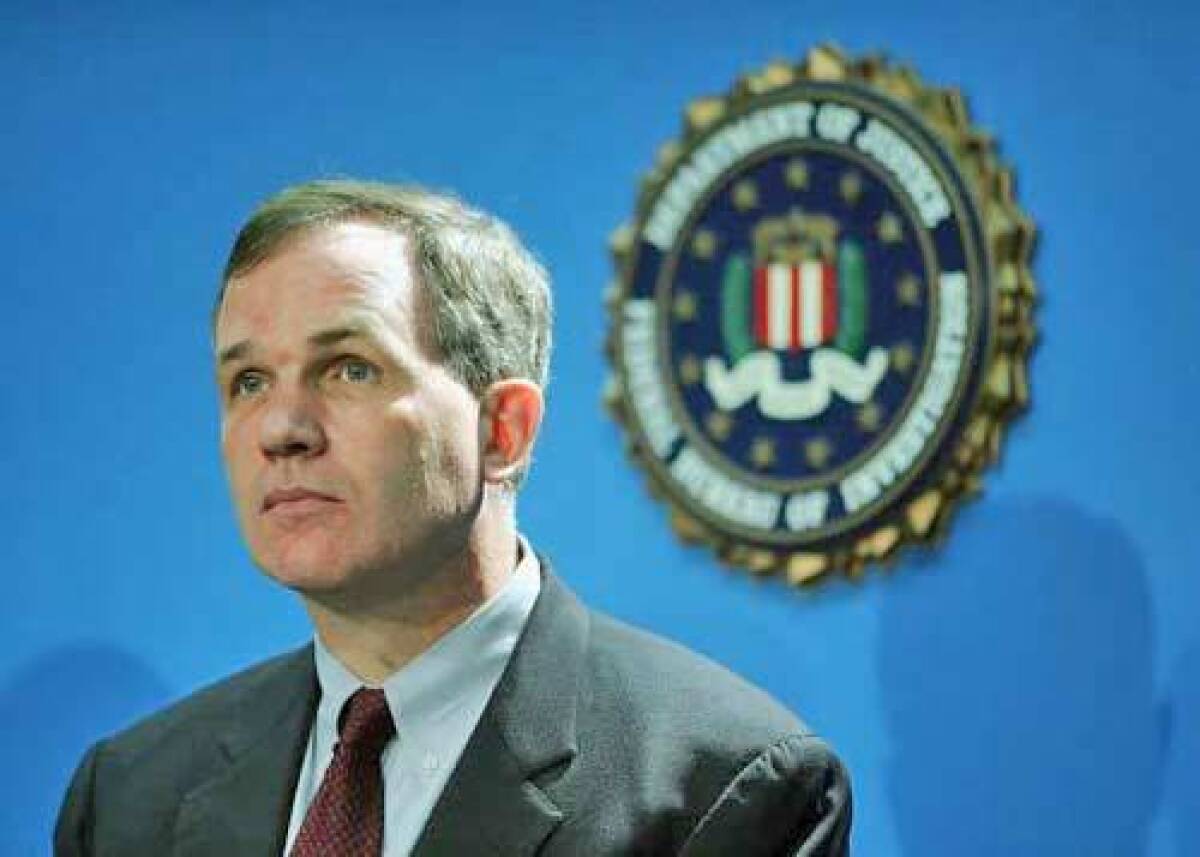

Drizin saw an opening and sought out a former U.S. attorney, Patrick Fitzgerald, who had expressed interest in reversing wrongful convictions.

Fitzgerald, a former top federal prosecutor in Chicago who handled or oversaw some of the Justice Department’s most high-profile criminal cases, agreed to review the files.

“This was an important gut check for us,” Drizin said. “He doesn’t come from our background. He is a prosecutor who puts people away.”

The former prosecutor agreed with the Northwestern team’s assessments, and penned a crisp 29-page letter to Foxx’s office that poked holes in the boy’s confession and savaged the junk science that prosecutors used to link Hester to the crime. He also methodically laid out the case against the engineer.

Mark Rotert, who at the time led Foxx’s Conviction Integrity Unit, was impressed. After reviewing the files, Rotert and his attorneys concluded they would never have prosecuted Hester — the entire case was a mess.

“The thing that grabbed me at the beginning reading through it was the confession struck me as implausible,” Rotert said. “And I don’t think the police did a damned thing to investigate this murder once they put Lee Arthur into a police car. They missed a much better suspect. And the science has been discredited. There was nothing here.”

In May 2019, Rotert petitioned a court to toss the conviction. A judge agreed.

A more difficult decision for prosecutors loomed. Hester’s lawyers asked Foxx to not oppose their request for a certificate of innocence. Such a certificate, issued by a judge, would establish Hester was actually innocent, allowing him to obtain about $200,000 in compensation from the state for his time behind bars.

Prosecutors often did not support issuing such certificates unless evidence of innocence was concrete and overwhelming; Hester’s case did not seem so clear-cut. But as Foxx reviewed the files and arguments, she came to a conclusion. “Justice requires us even in the murkiest and oldest of cases to do what is right,” Foxx said. Prosecutors did not oppose the motion.

Justice came in January. In the same building where a grade-schooler six decades earlier had displayed no emotion when a jury found him guilty of murder, an old man wept as a judge declared his innocence, and recast the racist legacy of Illinois vs. Hester.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.