Defying predictions of disaster, Africa’s coronavirus response is receiving praise

- Share via

JOHANNESBURG, South Africa — At a lecture to peers this month, John Nkengasong showed some images that once dogged Africa, including a magazine cover declaring it “The Hopeless Continent.” Then he quoted Ghana’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah: “It is clear that we must find an African solution to our problems, and that this can only be found in African unity.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has fractured diplomatic relationships across the globe. But as director of the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Nkengasong has helped steer Africa’s 54 nations into an alliance praised as responding better than some richer countries, including the United States.

A onetime official at the U.S. CDC, Nkengasong modeled Africa’s version of the agency after his former employer, whose current struggles under President Trump pain him. In an interview with the Associated Press, he didn’t name Trump but cited “factors we all know” with regard to the CDC’s problems.

While the U.S. nears 200,000 COVID-19 deaths and the world approaches 1 million, Africa’s surge has been leveling off. Its 1.4 million confirmed cases are far from the horrors predicted. Antibody testing is expected to show many more infections, but most cases are asymptomatic.

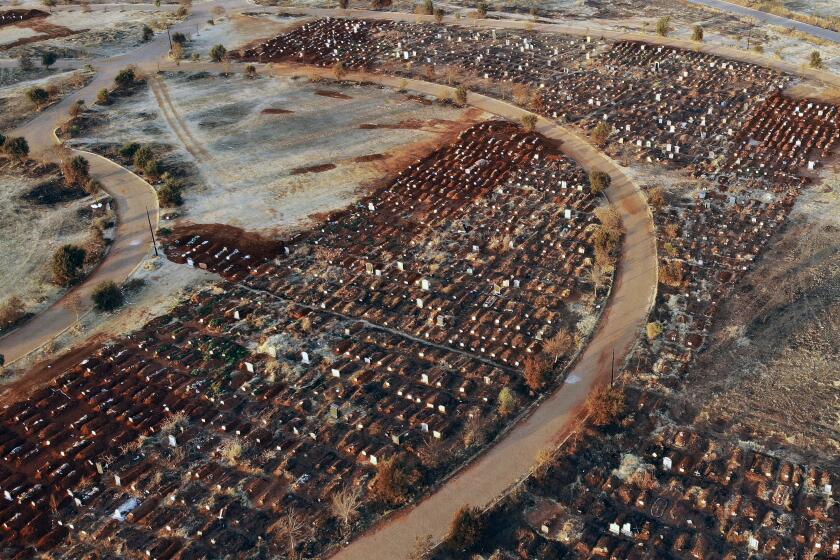

Slightly more than 34,000 deaths have been confirmed on the continent of 1.3 billion people. Health experts point to Africa’s youthful population as a factor in why COVID-19 hasn’t taken a larger toll, along with swift lockdowns and the later arrival of the virus than in Asia, Europe and North America.

“Africa is doing a lot of things right the rest of the world isn’t,” said Gayle Smith, a former administrator with the U.S. Agency for International Development. She’s watched in astonishment as Washington looks inward instead of leading the world. But Africa “is a great story and one that needs to be told.”

Africa’s confirmed coronavirus cases surpass 1 million, but global health experts say the true toll is much higher

Nkengasong, whom the Gates Foundation is honoring Tuesday with its Global Goalkeeper Award as a “relentless proponent of global collaboration,” is the continent’s most visible spokesperson on the pandemic. The Cameroon-born virologist insists that Africa can stand up to COVID-19 if given a fighting chance.

Early modeling assumed “a large number of Africans would just die,” Nkengasong said. The Africa CDC decided not to issue projections. “When I looked at the data and the assumptions, I wasn’t convinced,” he said, adding: “There’s a lot we still don’t know.”

He and other African leaders are haunted by the memories of 12 million Africans dying of AIDS during the decade it took for affordable HIV drugs to reach the continent. That must not happen again, he said.

As Africa’s top public health official, leading an agency launched only three years ago, Nkengasong plunged into the race for medical supplies and now a vaccine. At first, it was a shock.

As the coronavirus spreads in Africa, it threatens those who earn their living on the streets, including sex workers with HIV.

“The collapse of global cooperation and a failure of international solidarity have shoved Africa out of the diagnostics market,” Nkengasong wrote in the journal Nature in April. “If Africa loses, the world loses.”

Supplies slowly improved, and African countries have conducted 13 million tests, enough to cover 1% of the continent’s population. But the ideal is 13 million tests per month, Nkengasong said.

He urges African countries not to wait for help from abroad, rejecting the image of the continent holding out a begging bowl.

Acting on that encouragement, Africa’s public and private sectors, led by the African Union, have created an online purchasing platform to concentrate their negotiating power and to buy directly from manufacturers. Governments can browse and buy rapid-testing kits, N95 masks and ventilators, some of which are now manufactured in Africa in another campaign endorsed by heads of state.

Antibodies that fight coronavirus infection last at least four months and do not fade quickly as some earlier reports suggested — a good sign for vaccines.

Impressed, Caribbean countries have signed on.

“It’s the only part of the world I’m aware of that actually built a supply chain,” said Smith, the former USAID chief.

When the pandemic began, just two African countries could test for the coronavirus. Now all can. Nkengasong was struck by how much information “doesn’t get translated” to member states, so the Africa CDC holds online training on everything from safely handling bodies to genomic surveillance.

“I look at Africa and I look at the U.S., and I’m more optimistic about Africa, to be honest, because of the leadership there and doing their best despite limited resources,” said Sema Sgaier, director of the Surgo Foundation, which produced a COVID-19 vulnerability index for each region. She made that remark even as Africa’s cases were surging weeks ago.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said new guidance that warned about the dangers of coronavirus transmission via aerosols was posted by mistake.

With COVID-19 vaccines the next urgent issue, African countries held a conference to insist on equitable access and explore manufacturing to end their almost complete reliance on the outside world. They began securing the late-stage clinical trials that long have been held outside the continent, aiming to land 10 as soon as possible.

Nkengasong said Africa needs at least 1.5 billion vaccine doses, enough to cover 60% of the population with the two likely required doses to develop “herd immunity.” That will cost about $10 billion.

The World Health Organization says Africa should receive at least 220 million doses through an international effort, known as COVAX, to develop and distribute a vaccine.

That’s welcome but not enough, Nkengasong said.

His next hurdle is how to deliver doses throughout the continent with the world’s worst infrastructure. Fewer than half of Africa’s countries have access to modern healthcare facilities, he said.

COVID-19’s effects are “devastating” on education, economies and the fight against other diseases in Africa, Nkengasong said. He plans a major conference next year to press countries to significantly increase health spending ahead of the next pandemic.

“If we do not,” he said, “something is terribly wrong with us.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.