China can expect Biden to keep pushing for change, with help from U.S. allies

- Share via

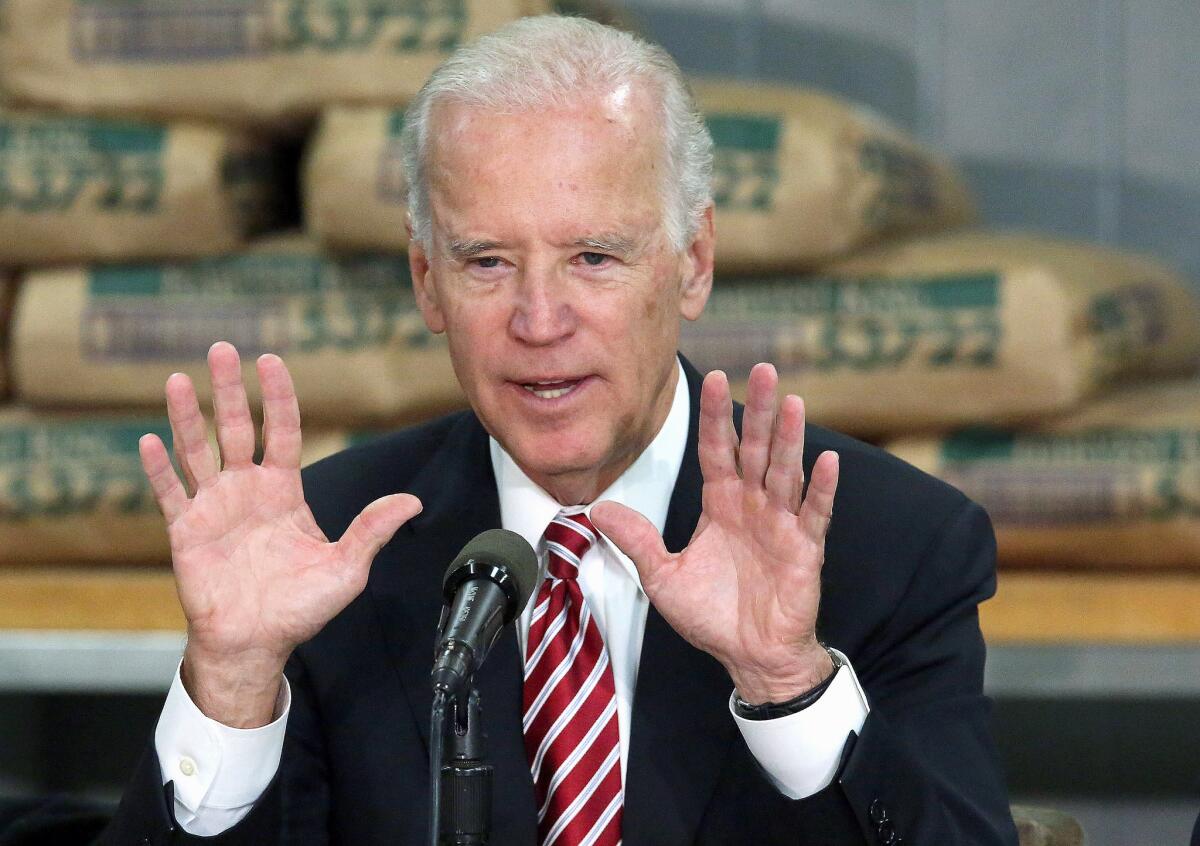

BEIJING — China is eyeing the U.S. election of Joe Biden as the next president warily, expecting that he could be just as formidable an adversary as the man he is replacing and perhaps even more effective.

Arguably the most vexing foreign policy challenge the Biden administration faces, China in recent years has emerged as a major world power, flexing economic and military muscle in the South China Sea, on its border with India and across entire continents.

The Trump administration has received some credit internationally for confronting Beijing with economic threats in an effort to check its growing influence. But many observers are hoping that Biden brings a more coherent approach and will work more closely with allies and partners who share a skepticism of China’s policies.

By shifting rhetoric and style, Biden’s aides say, he could assemble a more potent group of allies to stand up to China and President Xi Jinping. Trump was less successful in recruiting partners because of his bombastic America-first approach that alienated numerous other leaders — and pushed some countries closer to China.

At the same time, Biden and his advisors indicate they would be willing to open or cultivate some areas of cooperation with China, such as dealing with climate change.

Trump’s top diplomat, Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo, this week compared the administration’s policies toward China, including punishing tariffs and economic sanctions, to President Reagan’s challenge to the Soviet Union that preceded the fall of Communism.

But Biden, whose presidential inauguration is Jan. 20, has said getting tough with China must be a broader, more nuanced effort.

“The most effective way … is to build a united front of U.S. allies and partners to confront China’s abusive behaviors and human rights violations,” he wrote in a policy statement this year, “even as we seek to cooperate with Beijing on issues where our interests converge, such as climate change, nonproliferation, and global health security.”

Such a “united front” is what Beijing fears most, said Willy Lam, professor of history and China studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

“Trump is pushing an isolationist, America-first policy, whereas Biden will seek the views of American allies and friends and come up with a kind of united front against China,” Lam said. “This, the Chinese are most nervous about.”

The Chinese government is one of only a handful of major nations that have not congratulated Biden after vote counts from the U.S. presidential election Nov. 3 showed he beat Trump, saying it wanted to wait for final results. Trump had not conceded as of Wednesday.

Vice Foreign Minister Le Yucheng said at a news briefing last week that China hopes for cooperation with the U.S. in a “healthy and stable” relationship.

“We hope the new American administration will meet the Chinese side halfway to focus on cooperation and manage differences,” Le said.

Biden’s election could also bring more predictability to U.S.-China relations, said Shi Yinhong, director of the Center on American Studies at People’s University in Beijing.

“Compared with Trump, Biden-Harris is far less wild, far less vulgar, and far less erratic,” Shi wrote in an essay published by the Chinese website Ifeng News this week. “Thus it is expected that American policy and strategy toward China will become more predictable and stable,” especially because Biden has stated that he will prioritize diplomacy in foreign policy.

China experts and scholars said they expected a change in the tactics and style of U.S. policy toward China under a Biden administration but not in the essence of competition, confrontation and pressure to reform and desist from aggressive behavior. Biden’s expected focus on speaking about human rights has also raised some alarm bells in Beijing.

Shi suggested that China should take initiative by pulling back militarily and reducing tensions with other countries. Too many other nations “already have their own anger, dissatisfaction and condemnation of China,” he said, including Britain, Japan, Australia, Germany, India and others.

Trump began his administration by tearing up a 12-nation trade agreement, the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiated under President Obama, leaving Asian countries feeling jilted. He then pursued a baffling and ultimately failed rapprochement with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un while neglecting long-standing American friends in the region, leaving two treaty allies, Thailand and the Philippines, to continue to drift closer to China.

Trump scolded Asian nations for failing to buy enough U.S. goods while mocking their leaders, including Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi — and then disrupted their economies by escalating the trade war with China.

In a recent survey across 10 Southeast Asian countries, 47% of respondents said they had little or no confidence in the U.S. as a strategic partner, up from 35% a year earlier.

At the same time, U.S. opinion of China deteriorated. A recent poll by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank, found more than half of American citizens surveyed believed China to be the most serious challenge to the U.S., a 2-to-1 edge over Russia. Yet there remained potential areas of dialogue for those surveyed, said Michael Green, a former National Security Council official now at the think tank.

“They know we are in serious strategic competition with China, they consider China to be the No. 1 threat, by far, to our interests,” Green said. “But they don’t want to throw out the baby with the bath water, whether it’s academic exchange, climate change work, global health or working on North Korea.”

America’s return to multilateralism is welcome as a stabilizing force and important player in global issues such as climate change, said Wang Yong, professor of international studies at Peking University.

“But if some people in the U.S. use ideological standards to politicize these supposedly international organizations and make alliances against China because China’s ideology is different, then this is a big mistake,” he said. “This is what some people are worried about.”

The last four years under Trump have damaged American soft power across the world, including in China, Wang said.

“As American views of China became worse, Chinese people’s negative views of the U.S. have also become worse and worse,” he said.

Many Chinese resent what they see as U.S. bullying of China out of dislike for its growing strength. Under Trump, the flaws of a fractured America have also lessened its appeal among Chinese citizens. But the restoration of a vibrant democracy in the U.S. and its alliance with like-minded nations to spread democratic values abroad would be a threat to Chinese authorities.

“The U.S. ideology is expansionary, pushing American values and political systems everywhere, changing other countries’ systems,” Wang said. “China feels this kind of ideological threat.”

Analysts said they didn’t expect the Biden administration to return to the approach of the Obama years, which emphasized accommodating China, but predicted Biden would try to reduce the temperature in the dispute by easing the trade war and lifting some of the Trump administration’s tariffs.

Biden’s victory offers a chance for dialogue and cooperation that were not possible under the Trump administration, said Minxin Pei, professor of government at Claremont McKenna College.

Trump’s frequent references to a “China virus” in describing COVID-19 and Pompeo’s regular denunciations of China had made it impossible for Beijing to engage without losing face. In the last year, Chinese official voices had also degenerated into name-calling against the Trump administration.

Under Biden, “the tone will be different, and that is a huge improvement,” Pei said.

Two of the incoming Biden administration’s priorities — combating the pandemic and fighting climate change — are also China’s priorities. It will be easier for China to seek cooperation on such issues than to make any changes in Hong Kong and Xinjiang, Pei said: “Xi Jinping’s own political fortune is much more closely connected with these domestic issues than with foreign policy.”

It will be tricky for either China or the U.S. to “extend the first olive branch,” Pei said. Both Xi and Biden would have to fight a “two-front battle,” he said: “Biden will be dealing with Xi and with domestic critics and skeptics, and Xi will be doing the same.”

One avenue for Biden’s multilateral response to China would be a continuation in Trump’s interest in the Quad, an informal four-nation group comprising the U.S., Australia, Japan and India. The loose partnership of four large democracies has long been seen as a possible counterweight to Chinese influence and military power in the Indo-Pacific, but the members were reluctant to formalize the grouping for fear of antagonizing China, which views the Quad as hostile.

“When we join together with fellow democracies, our strength more than doubles,” Biden wrote in the policy statement. “China can’t afford to ignore more than half the global economy. That gives us substantial leverage to shape the rules of the road.”

Su reported from Beijing, Bengali from Singapore and Wilkinson from Washington.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.