Azerbaijanis who fled war in Nagorno-Karabakh look to return home — if it exists

- Share via

BAKU, Azerbaijan — As Azerbaijan regains control of land it lost to Armenian forces a quarter-century ago, civilians who fled the fighting back then wonder if they can go back home now — and if there’s still a home to go back to.

An estimated 800,000 Azerbaijanis were displaced in the 1990s war that left the Nagorno-Karabakh region under the control of ethnic Armenian separatists and large adjacent territories of Azerbaijani land in Armenia’s hands. During six weeks of renewed fighting this fall, which ended with a truce Nov. 10, Azerbaijan took back parts of Nagorno-Karabakh itself and sizable swaths of the outlying areas.

More territory is being returned as part of the cease-fire agreement that stopped the latest fighting. But as Azerbaijani forces discovered when the first area, Aghdam, was turned over Friday, much of the recovered land is uninhabitable. The city of Aghdam, where 50,000 people once lived, is now a shattered ruin.

Adil Sharifov, 62, who left his hometown in 1992 during the 1990s war and lives in Azerbaijan’s capital, Baku, knows he will find similar devastation if he returns to the city of Jabrayil, which he longs to do.

Jabrayil is one of the outlying areas regained by Azerbaijani troops before the recent fighting ended. Soon after it was taken, one of Sharifov’s cousins went there and told him that the city was destroyed, including the large house with an orchard where Sharifov’s family once lived.

Nonetheless, “the day when I return there will be the greatest happiness for me,” he said.

Deadly fighting over Nagorno-Karabakh has caused grief and anger. But for many Azerbaijanis displaced by the conflict, it’s also brought hope.

For years, he said, his family had followed reports about Jabrayil on the internet. They knew the destruction was terrible, but Sharifov’s late mother maintained a desperate hope that their house had been spared and held on to the keys.

“I will build an even better house,” Sharifov vowed.

Ulviya Jumayeva, 50, can go back to better, though not ideal, circumstances in her native Shusha, a strategically located city that Azerbaijani forces retook in their recently ended offensive. (Armenians calls the city Shushi.)

Her younger brother, Nasimi, took part in the battle and phoned to tell her that the apartment their family fled in 1992 was intact, though mostly stripped of the family’s possessions.

Column One: Armenian Americans marvel at an elder’s generosity as they grieve over an ancestral home

Clara Margossian, 102, built a life in Fresno after her family fled the Armenian genocide. With the war in Nagorno-Karabakh, she has given $1 million to help Armenia, a homeland she’s never seen.

“According to him, it is clear that Armenians lived there after us, and then they took everything away. But our large mirror in the hallway, which we loved to look at as children, remains,” Jumayeva said, adding: “Maybe my grandchildren will look in this mirror.”

“We all have houses in Baku, but everyone considered them to be not permanent, because all these years we lived in the hope that we would return to Shusha,” she said. “Our hearts, our thoughts have always been in our hometown.”

But she acknowledged that her feelings toward Armenians have become more bitter.

“My school friends were mostly Armenian. I never treated ordinary Armenians badly, believing that their criminal leaders who unleashed the war were to blame for the massacre, war and grief that they brought to their people as well,” Jumayeva said.

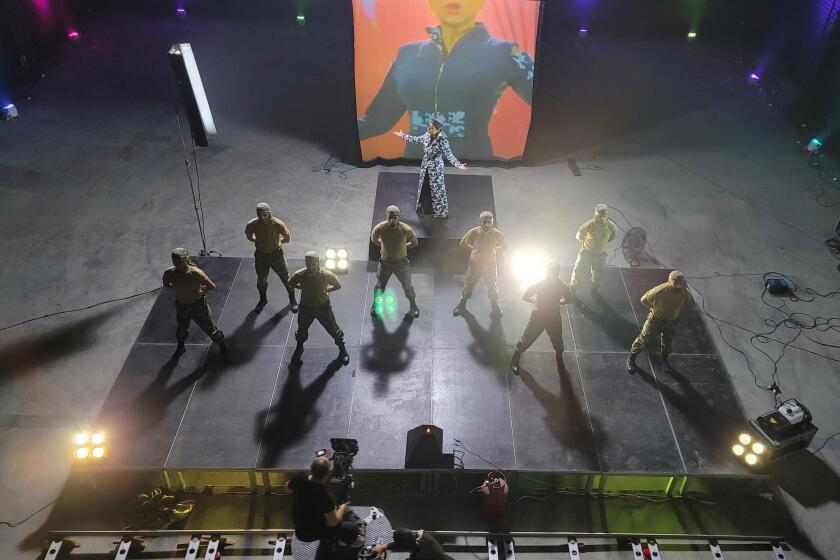

Armenia and Azerbaijan enlist artists, lobbyists and online activists in a 21st century propaganda war in their fight over Nagorno-Karabakh.

”But after the current events, after the shelling of peaceful cities ... after the Armenians who are now leaving our territories, which are even outside of Karabakh, burn down the houses of Azerbaijanis in which they lived illegally ... something fractured in me. I changed my attitude toward them,” she said. “I understood that we Azerbaijanis will not be able to live peacefully next to the Armenians.”

While Sharifov has less to go back to, he has a more moderate view, saying the two ethnic groups, with their different religious traditions, still have the potential to live together amicably.

“If the Armenians observe the laws of Azerbaijan and do not behave like bearded men who came to kill, then we will live in peace,” he said. “The time to shoot is over. Enough casualties. We want peace. We do not want war.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.