Rwandan report blames France for ‘enabling’ the 1994 genocide

- Share via

PARIS — The French government bears “significant” responsibility for “enabling a foreseeable genocide,” a report commissioned by the Rwandan government says of France’s role in the horror in which an estimated 800,000 people were slaughtered in Rwanda in 1994.

The 600-page report, which the Associated Press has read, comes amid efforts by Rwanda to document the role of French authorities before, during and after the genocide. The report says that France “did nothing to stop” the massacres in April and May 1994 and, in the years after the genocide, tried to cover up its role and even offered protection to some perpetrators.

The report is to be made public Monday after its formal presentation to Rwanda’s Cabinet.

It concludes that, in years leading up to the genocide, former French President Francois Mitterrand and his administration had knowledge of preparations for the massacres yet kept supporting the government of then-Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana despite the “warning signs.”

“The French government was neither blind nor unconscious about the foreseeable genocide,” the authors of the report wrote.

The Rwandan report comes less than a month after a French report, commissioned by Macron, concluded that French authorities had been “blind” to the preparations for genocide and then reacted too slowly to appreciate the extent of the killings and to respond to them. It concluded that France had “heavy and overwhelming responsibilities” by not responding to the drift that led to the slaughter of ethnic Tutsis and the moderate Hutus who tried to protect them. Groups of extremist Hutus carried out the killings.

The terrorism trial for Paul Rusesabagina, whose story inspired the film ‘Hotel Rwanda,’ is set to start on Wednesday.

Macron commissioned that report in an effort to improve relations with Rwanda.

Rwanda, a small but strategic Central African nation of 13 million people, is “ready” for a “new relationship” with France, Rwandan Foreign Affairs Minister Vincent Biruta told the Associated Press.

“Maybe the most important thing in this process is that those two commissions have analyzed the historical facts, have analyzed the archives which were made available to them and have come to a common understanding of that past,” he said. “From there we can build this strong relationship.”

The Rwandan report, commissioned in 2017 from the Washington law firm of Levy Firestone Muse, is based on a wide range of documentary sources from governments, non-governmental organizations and academics, including diplomatic cables, documentaries, videos and news articles. The authors also said they had interviewed more than 250 witnesses.

Gospel singer Albert Nabonibo shocked many Rwandans in August when he revealed that he is gay in a country that largely reviles homosexuality.

In the years before the genocide, “French officials armed, advised, trained, equipped, and protected the Rwandan government, heedless of the Habyarimana regime’s commitment to the dehumanization and, ultimately, the destruction and death of Tutsi in Rwanda,” the report says.

French authorities at the time pursued “France’s own interests, in particular the reinforcement and expansion of France’s power and influence in Africa.”

In April and May 1994, at the height of the genocide, French officials “did nothing to stop” the massacres, says the report.

Operation Turquoise, a French-led military intervention backed by the United Nations which started June 22, 1994, “came too late to save many Tutsi,” the report says.

It adds that the authors found “no evidence that French officials or personnel participated directly in the killing of Tutsi during that period.”

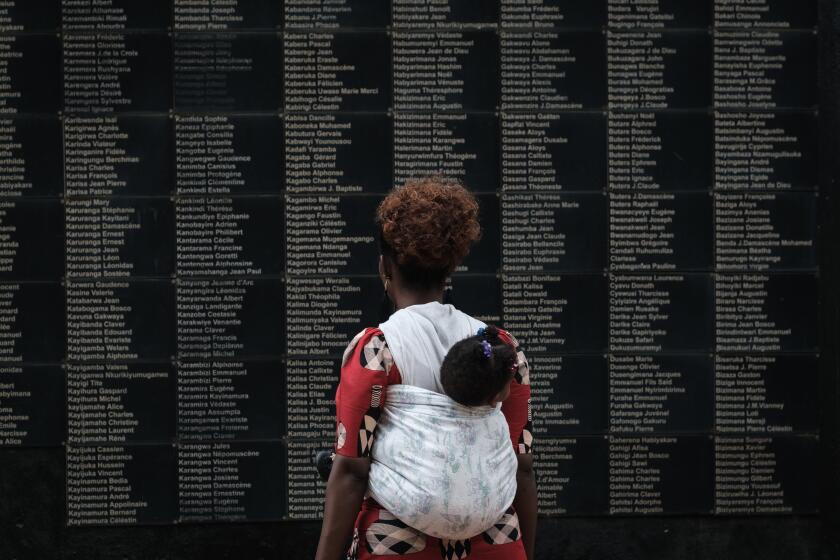

A valley dam that authorities in Rwanda say could contain about 30,000 bodies was discovered more than a quarter-century after the country’s genocide.

This finding echoes the conclusion of the French report, which cleared France of complicity in the massacres, saying that “nothing in the archives” demonstrates a “willingness to join a genocidal operation.”

The Rwandan report also addressed the attitude of French authorities after the genocide.

Over the last 27 years, “the French government has covered up its role, distorted the truth, and protected” those who committed the genocide, it says.

The report suggests that French authorities made “little efforts” to send to trial those who committed the genocide. Three Rwandan nationals have been convicted of genocide so far in France.

It also strongly criticizes the French government for not making public documents about the genocide. The government of Rwanda notably submitted three requests for documents in 2019, 2020 and this year, all of which the French government ignored, according to the report.

News Alerts

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Under French law, documents regarding military and foreign policies can remain classified for decades.

But things may be changing.

On April 7, the day of commemoration of the genocide, Macron announced a decision to declassify and make accessible to the public the archives from 1990 to 1994 that belong to the French president and prime minister’s offices.

Rwandan President Paul Kagame praised the French-commissioned report as “a good thing,” welcoming efforts in Paris to “move forward with a good understanding of what happened.”

Félicien Kabuga, a Rwandan long wanted for his alleged role in supplying machetes to the killers, was arrested outside Paris in May.

And in July, an appeals court in Paris upheld a decision to end a years-long investigation into the plane crash that killed Habyarimana and set off the genocide. That probe irked Rwanda’s government because it targeted several people close to Kagame for their alleged role, charges they denied.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.