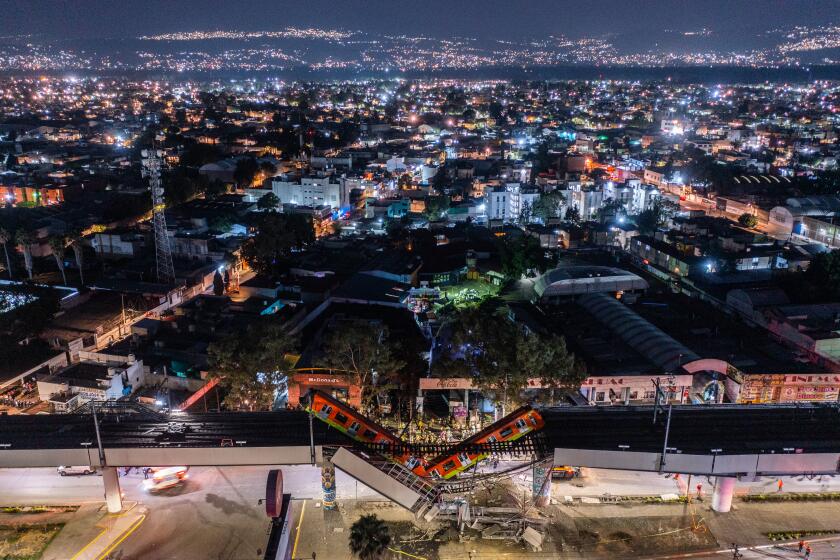

In Mexico, a deadly train wreck that many saw coming

A Mexico City Metro overpass collapsed, sending part of a train plunging onto the road below, trapping cars and killing at least 23 people.

- Share via

MEXICO CITY — It was dubbed the “Golden Line,” the shiny and pricey showpiece of a Mexico City Metro system long plagued by overcrowding, crime and sketchy service.

But the $2-billion new addition, inaugurated with much fanfare in 2012 and formally known as Line 12, soon became infamous for what critics considered shoddy design, safety shutdowns and allegations of corruption in its construction.

On Monday night, Line 12 was the site of the deadliest Metro incident in almost 50 years: An overpass collapsed beneath the weight of an elevated passenger train and sent a section of the train plunging toward the bustling avenue below.

At least 24 people were killed and 79 injured, said city authorities who Tuesday blamed “structural damage” for the sudden and catastrophic failure of beams holding up the Metro viaduct. Officials vowed a thorough investigation into why the structure collapsed as the train was pulling into the Olivos Metro station.

For many straphangers and residents of the working-class districts of southern Mexico City served by Line 12, Monday’s crash was a tragedy foretold. Some say they had complained for years about cracks in the structure and other seeming irregularities.

“We knew this was going to happen,” said Juan Antonio Balderas Hernández, 58, a street vendor and resident of Tláhuac borough. “Sooner or later, this was just bound to happen.”

A sense of collective grief and anger gripped much of the capital on Tuesday. Trending on social media and appearing in graffiti was the phrase: “It wasn’t an accident. It was negligence.” #NoFueAccidenteFueNegliencia

More than 8,000 Metro workers said they were planning a walkout to protest what they called the system’s substandard conditions. A date had not been set.

“A bridge as new as this should not fall down,” Fernando Espino, secretary of the union representing Metro workers, told the Spanish daily El País.

The Metro director, Florencia Serranía, said she would not accede to demands that she resign as head of a system that provides transport to more than 4 million people daily on workdays.

A glimpse at the history of the troubled line suggests that multiple Mexican administrations ignored warning signs about the potential for tragedy.

Authorities shut down much of Line 12’s elevated stretches in 2014 amid safety concerns. A 2014 congressional investigation into Line 12 found major problems, including design flaws, poor quality materials and “deficient, hasty and incomplete certification of the functionality and safety of the line.”

The entire line was reopened more than a year and a half later after repairs. But questions remained about its safety — even as more than 220,000 commuters rode it each day.

The Metro’s 2018-2030 master plan called for millions of dollars to be invested in the maintenance of Line 12, warning of possible derailments if the government did not address its problems. It is not clear if the additional funds were ever earmarked.

As National Guard troops on Tuesday combed through mangled steel and chunks of concrete at the crash site and rescuers used a crane to try to stabilize a rail car dangling precariously from the overpass, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador pledged a full investigation.

“The people of Mexico have to know the whole truth — nothing will be hidden from them,” he said at his daily news conference.

Mexico City’s mayor, Claudia Sheinbaum, echoed his pledge, saying a Norwegian firm would lead an independent inquiry. Mexico City’s attorney general’s office said it had launched a homicide investigation into the incident.

The Mexican flag stood at half staff in the capital’s central plaza as condolences poured in from across the world, including from the White House.

Authorities could provide no breakdown for how many of the dead and injured had been riding in the stricken train and how many were on the street below in vehicles hit by falling debris.

The inauguration of Line 12 in October 2012 was a major event in the capital, with attendees including Marcelo Ebrard — then the Mexico City mayor, currently Mexico’s foreign secretary — and Carlos Slim, Mexico’s richest man. Slim’s construction company was part of a multi-national consortium that participated in the four-year construction of Line 12, which was completed 10 months after its target date.

The devastating central Mexico earthquake of 2017 brought complaints from residents and commuters of cracks in supporting columns of Line 12. Officials said those problems had been repaired.

But, more recently, some residents said they had observed signs that the overpass was weakening.

“We all saw that the steel [supports] were buckling,” said Balderas, who was among many neighborhood residents who rushed to the scene of the accident. “I noticed it more than a month ago.”

Serranía, the head of the Metro system, told journalists that reports of steel supports on the overpass buckling before the crash were not true. But many passengers and neighborhood residents said they had little faith in the system.

“The crime is corruption, negligence, abuse of power and I would say homicide,” said Carlos Medina, 54, an Uber driver whose nephew, Alberto Medina Ortega, 33, was among the train passengers injured in the crash, suffering multiple fractures.

“I just ask that there is justice and that those responsible are punished,” said Medina, who was interviewed outside a hospital where his nephew was being treated.

Among the daily users of Line 12 was Juan Luis Diaz Galindo, a 38-year-old chauffeur. He was returning home Monday after a long day at work when the overpass collapsed at about 10:22 p.m.

His wife, Juliana Torres, and the couple’s teenage son called his cellphone over and over after they heard about the accident. No one answered. He had died in the crash.

Everyone using the train was aware that the line was possibly unsafe, his widow said.

“It was well known,” she said. “But unfortunately we rode it because of the economy and because it was convenient.”

At least 23 people died in an overpass collapse on the Mexico City Metro, which is among the busiest in the world.

Gregg Brandow, a professor of civil engineering at USC, said the suddenness of the overpass collapse suggested it may have been caused by fractures in the steel girders, long horizontal beams that span the distance between vertical supports. Topping the girders is the concrete super-structure that holds the train tracks. He said shoddy welding could have contributed to problems.

“If you have defects in the welding those can turn into a crack and that crack can just race across the steel and make it break,” said Brandow, who has viewed video of the incident but is not part of any formal investigation.

Such fissures are often visible during inspections, he said, but not always. “It often depends on how diligent you are in looking,” Brandow said.

Mexico City officials said recent inspections had not revealed any problems in the Line 12 structure.

Monday’s crash raised new questions about ex-mayor Ebrard’s role in the construction and funding of Line 12. The foreign secretary is considered a leading presidential candidate for the 2024 elections.

In a Twitter message, Ebrard called Monday’s collapse “a terrible tragedy,” sent condolences to the families of the victims and said he was at investigators’ full disposal.

Appearing alongside López Obrador at Tuesday’s news conference, Ebrard said: “If you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear.”

The crash could also have political repercussions for Sheinbaum, another potential presidential contender.

Monday’s crash was the deadliest accident on the Mexico City Metro since a collision of two trains Oct. 20, 1975, killed 31 and injured 70. It was the third fatal accident in the last 14 months.

In January, a fire in a Metro substation left one person dead and 29 injured, and disrupted service for weeks. In March 2020, a crash in the Tacubaya station killed one person and injured 41.

Special correspondent Liliana Nieto del Río contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.