Ammon Bundy seizes on housing shortage in new bid to take public lands in Idaho

- Share via

MERIDIAN, Idaho — When Ammon Bundy announced his run for governor of Idaho during a recent barbecue, he cooked up quarter-pound “Bundy burgers” made from a cow that his father unlawfully grazed on federal lands, part of a rebellion that triggered an armed standoff with authorities in 2014.

The sizzling patties conveyed that Bundy, despite pursuing something so mainstream as running for office, remains the defiant anti-government militant who has earned folk-hero status with the far right. He’s still focused on radically reducing federal land ownership in the West, property that belongs to the U.S. public but is coveted by ranchers, farmers, developers and others.

“When you lose control of the land, you lose control of everything,” Bundy said standing on an outdoor stage between cardboard cutouts of Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump, both of whom favored opening federal lands to development. “History and human nature demonstrate that if we build up and create dense and congested cities with large populations, traffic and pollution, we will lose our conservative, traditional values.”

Bundy is reframing the decades-long but narrow fight of his father, Cliven Bundy, against the Bureau of Land Management — the other BLM, as it’s known here — into a platform with broader appeal. He wants to use the governorship to wrest ownership of federal land for state control. It’s a campaign aimed at voters dreaming of wide open spaces and homes they can afford, wrapped in an idealized view of western life where land and resources are limited only by an unwillingness to use them.

Neither America nor the Gem State, he told the crowd, can survive the liberal creep of growing cities or the economic toll of too few houses for too many people. To “keep Idaho Idaho,” as his slogan promises, growth needs to happen out instead of up, as he puts it.

The federal government is “forcing everybody down into big cities and where they’re just surviving,” Bundy said in a recent interview with The Times. He spoke from his home outside Boise on five acres of apple orchards in an agricultural area known as Treasure Valley, surrounded by public lands.

His is a message laced with undertones of violence, conspiracy theories and a concept of God (Bundy is a devout Mormon) that includes a belief in Manifest Destiny. In Bundy’s worldview, preservationists and regulators are enemies, and sneaky ones at that. “They infiltrate government ... in order to force their ideological religious beliefs,” he said.

Environmentalists “don’t believe that God created the earth for man,” he said.

“They don’t believe, therefore, that man is anything more than another species that has evolved intellectually. And so they believe that it is their duty to create a disadvantage to humans, to balance the species,” he said.

Five years ago, Bundy led an armed occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon to protest the prosecution of two ranchers accused of setting fires on federal lands.

Two years before that, he helped lead hundreds of supporters in an armed confrontation in Nevada to stop a roundup of his father’s cattle, which ended with the government backing down (Bundy did not carry a weapon himself). Yet while Bundy faced federal prosecutions for both of these standoffs — and spent years in jail awaiting trials — he wasn’t convicted in either case.

“He fought the law and won,” said Devin Burghart, who tracks Bundy as executive director of the Institute for Research and Education on Human Rights.

Last week, that winning streak ended. Bundy was convicted by an Idaho jury on minor misdemeanor charges for trespassing and obstructing or resisting an officer, stemming from an August protest at the Idaho Capitol(which he is now banned from entering for a year).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Bundy capitalized on his government overreach argument and grew his base by leading multiple anti-lockdown and anti-mask protests, resulting in police arresting him five times, including the trespass incident related to his conviction.

His first court loss — for which he must pay a $750 fine and perform community service — is unlikely to hurt his run for governor, and may help it, said Boise State political science professor Ross Burkhart.

Some voters may be attracted to Bundy’s claims that “he is a victim of the state suppressing his right to free speech,” Burkhart said.

Rachel Goldwasser, a research analyst with the Southern Poverty Law Center, said Bundy’s sense of righteousness scares her.

“He’s not interested in what the masses want; he’s interested in what he believes is right,” Goldwasser said. “If he believes the thing he is opposing is unconstitutional, then lawlessness is acceptable. If it’s patriotic, lawlessness is acceptable.”

::

Across much of the rural West, tensions are escalating — and anger at government ratcheting to extremes — as the climate warms, fires rage, droughts worsen and population grows.

Bundy says that insurgency can be justified in places where federal rules hamper the use of natural resources, and preaches that the Constitution forbids the federal government to own many lands it claims. It’s a message that appeals beyond Idaho, especially for those in agriculture who fear their livelihoods are being regulated to death.

The election of President Biden means that opponents of federal environmental laws no longer have a friend in the White House and agencies such as the Department of the Interior. Biden has pledged to triple the amount of protected land in the U.S. by 2030 and enforce laws such as the Endangered Species Act.

In the western United States, ownership of land means access to water rights, and in no other part of the country is the federal government such a large landlord — or steward, depending on your point of view. In Nevada, 80% of the land is in federal control, as is 62% in Idaho, 52% in Oregon, 45% in California, and 29% in Washington.

Federal land practices also fueled the Sagebrush Rebellion of the 1970s that sought state control of public forests and range land. Reagan’s election gave the rebels some hope, but he and Interior Secretary James G. Watt were unable to significantly shift federal land ownership.

“You have always had anti-government extremists who have a fundamental belief that land should belong to them individually,” said Aaron Weiss, deputy director of the Center for Western Priorities, a Denver-based conservation organization. Weiss said that water rights have always been central to that brawl.

“You go all the way back to the first time you had white settlers invading the West, displacing Indigenous people, you will find fights over water,” Weiss said. “Because, at the end of the day, the West is dry.”

::

At the Oregon and California border, Bundy is in the thick of a dire struggle over water.

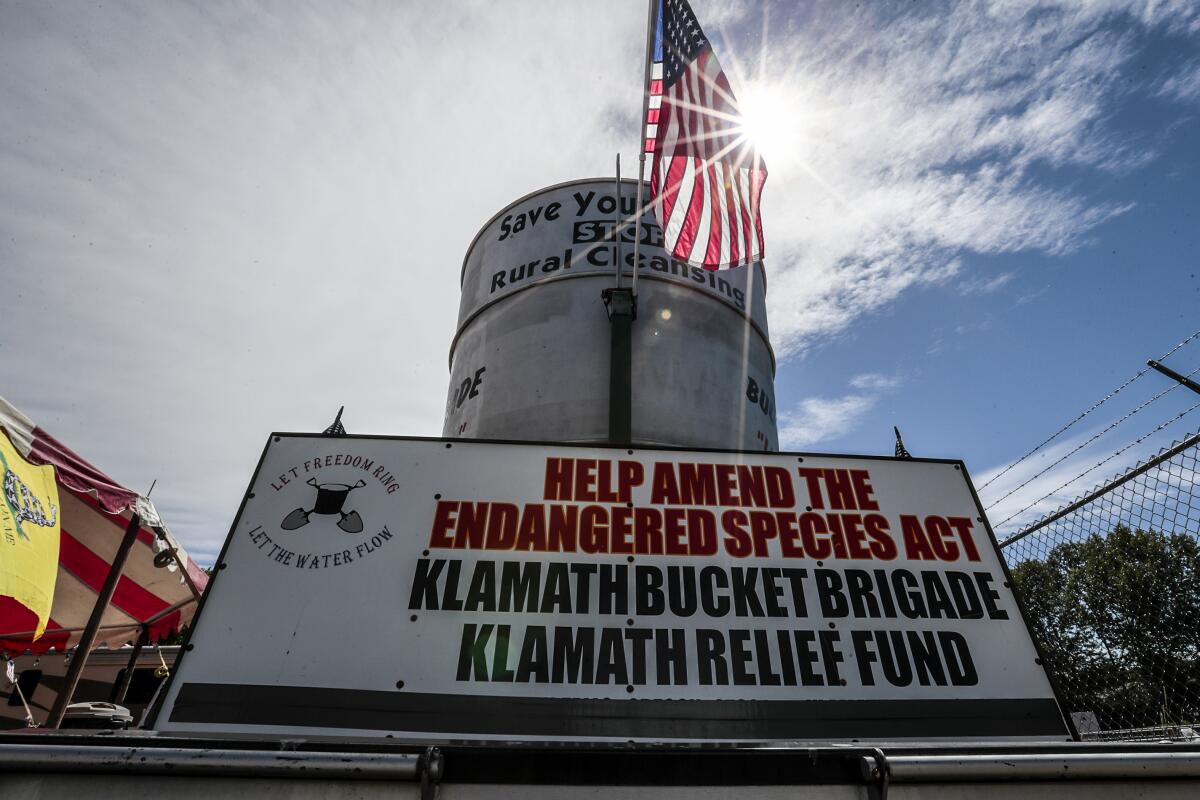

There, a group of activists aligned with him have threatened to forcibly take control of irrigation gates in Klamath Falls, Ore., where federal regulators have cut off annual water flows to family farms amid a drought that threatens endangered fish sacred to Native American tribes. The activists in Klamath Falls have erected a red and white circus tent, dubbed the Water Crisis Info Center, on private property just feet from the irrigation gates.

Bundy has pledged his support to the activists, one of whom, Dan Nielsen, stormed the Idaho Capitol with him last year. Bundy and Nielsen both confirmed they are in regular communication.

Recently, Nielsen said he is waiting to see if the water issue can be returned to state courts before taking action, but Bundy said withholding the water is “pure theft” and that if courts fail to back Nielsen, “I’ll go stand with him, and I know that there are thousands of people that will as well.”

The protesters are part of the People’s Rights Network, an organization that Bundy launched last year at the height of coronavirus restrictions. Using a proprietary internet platform, tens of thousands of members can communicate with one another, potentially summoning gun-toting supporters to scenes of protests.

Standing in his kitchen, Bundy recently used his smartphone to pull up the latest stats for People’s Rights — nearly 60,000 members organized in 29 states and Canada, all promising to protect their fellow members if called, he claimed. Bundy is quick to describe it as a linked network of “neighbors” who make independent choices and are not under his direction.

But Bundy does make calls to action, though often veiled. He recently posted a video on his YouTube channel, explaining how he sees America at this moment, using a mildew infecting his orchard as a metaphor. The fungus, he said, can’t be easily beat; the blighted branches have to be cut off and burned.

Without such drastic measures, Bundy warned, a nearby stand of saplings, with roots too young to fight the “invasive species” on their own, could die. The saplings, he said, were like “our children.”

Asked during an earlier phone interview who were the invasive species threatening future generations, Bundy said, “That’s a really good question. Maybe I don’t want to answer it.”

Black Lives Matter has emboldened a younger generation of the Klamath Tribes, who are now speaking out on their treatment on the parched Oregon-California border.

Then he continued, “Right now, I can say the agents in the Bureau of Reclamation in Klamath Falls, they’re certainly invasive species. They’re literally coming in, and they become parasites upon the people’s rights in that area.”

That kind of rhetoric has permeated the water crisis in Klamath Falls, and to some extremist trackers reveal a more disturbing picture of Bundy’s supporters.

In June, People’s Rights welcomed a guest speaker to the Klamath County Fairgrounds: a far-right activist who has claimed the proposed removal of four dams along the Klamath River is part of an “Agenda 21 method on how to control all people.”

Agenda 21 — a nonbinding 1992 United Nations resolution that encourages global sustainable development — has become fodder for conspiracy theorists who claim it is part of a plot to create one global government and trample freedoms in the name of environmentalism.

On a right-wing Telegram channel called Patriot Party California, an antisemitic message claimed the Klamath water shut-off was the work of so-called globalists who are “creating an artificial drought and an intentional food shortage.”

“Jews have made a move to starve Americans by cutting off the water supply to 1000’s of farms from Oregon to California,” the message read.

Goldwasser, with the Southern Poverty Law Center, said the Klamath Falls fight is playing out in an area that is “somewhat of a hotbed for white nationalism.” She said it has drawn the attention of militias and secessionists who support the creation of the State of Jefferson out of rural counties in Northern California and southern Oregon.

“Any time you have gun owners — open carriers whenever possible — that also have an anti-government mind-set to the point of anger and grievance, there’s always the possibility of violence,” she said.

::

Boise State political science assistant professor Charlie Hunt says Bundy’s shot at occupying the Idaho governor’s mansion is unlikely but not out of the question. Though the Idaho Republican Party has disavowed Bundy, ultra-conservative politics are the norm here, he said.

The lieutenant governor, considered Bundy’s main primary competition, is an ardent Trump supporter whom Hunt compares to Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-Ga.), who supports conspiracy theories.

“It’s Idaho and there are plenty of voters who share those [far-right] views,” Hunt said. “The loudest voices in Idaho tend to be voices like Bundy.”

Burkhart, the political expert, points out that Bundy has name recognition and a fervent base. The tension in Idaho is less than in the Klamath basin, he said, but “if the exceptional drought spreads, then the political climate for Bundy becomes more favorable.”

Bundy, who supports himself and his six children largely from income from commercial investment properties, is taking the next year to run a grass-roots campaign, in which he’s promising to accept any invitation to speak that comes with a crowd of 50 people or more — including gatherings of urban liberals, whom he says he can convert to his way of thinking. His platform also includes an end to state income and property taxes.

Bundy, best known for leading the 2016 armed occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, has launched a militia network that he describes as ‘neighborhood watch on steroids.’ Experts say it has strong overlap with right-wing extremist groups.

Even detractors acknowledge he has a potent combination of everyman charm and cowboy swagger that still holds sway here, along with a clear framework of religious principles (including a promise to ban abortion) that win votes in this largely Christian state. Bundy said he believes his message will resonate even in the cities he scorns because the affordable housing crisis crosses party lines.

One of his daughters is 18 and thinking of marrying her sweetheart. She plans to train to be a masseuse and her boyfriend has college plans. Bundy wonders how they will ever afford a housing payment. His property, for which he paid nearly $600,000 six years ago, is now worth double that — a mortgage the young couple couldn’t manage, he said.

The average home price in Idaho is about $390,000, according to real estate tracker Zillow, an increase of nearly 28% from a year ago. Flooding the market is how he sees homes becoming attainable for future generations.

“It is important to know that the historical American dream was rooted in property ownership. In order for people to feel prosperous, secure and happy, they have to have their own home,” Bundy, wearing a trademark Stetson, told the cheering crowd at his kickoff event, which drew about 400 people, though organizers claimed 700.

“To create affordable housing for the young and the old alike, we simply need more supply. And to have more supply, we need to take our lands back.”

Chabria reported from Meridian and Klamath Falls and Branson-Potts from Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.