Academics at UC Berkeley, Stanford and MIT win Nobel Prize in economics

- Share via

STOCKHOLM — Three U.S-based economists won the Nobel Prize in economics on Monday for pioneering research on the labor market effects of minimum wage, immigration and education, and for creating the scientific framework to allow conclusions to be drawn from such studies that can’t use traditional methodology.

Canadian-born David Card, who teaches at UC Berkeley, was awarded one half of the prize, while the other half was shared by Joshua D. Angrist from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Dutch-born Guido W. Imbens, who teaches at Stanford University. The award is formally known as the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said the three have “completely reshaped empirical work in the economic sciences.”

Together, the researchers helped rapidly expand the use of “natural experiments,” or studies based on the observation of real-world data. Such research made economics more applicable to everyday life, provided policymakers with actual evidence on the outcomes of policies, and in time spawned a more popular approach to economics epitomized by the blockbuster bestseller “Freakonomics,” by Stephen Dubner and Steven Levitt.

In a study published in 1994, Card looked at what happened to jobs at Burger King, KFC, Wendy’s and Roy Rogers when New Jersey raised its minimum wage from $4.25 to $5.05, using restaurants in bordering eastern Pennsylvania as the control — or comparison — group. Contrary to previous studies, he and his late research partner, Alan Krueger, found that an increase in the minimum wage had no effect on the number of employees.

The research fundamentally altered economists’ views of such policies. As noted by the Economist magazine, in 1992 a survey of the American Economic Assn.’s members found that 79% agreed that a minimum-wage law increased unemployment among younger and lower-skilled workers. Those views were largely based on traditional economic views of supply and demand: If you raise the price of something, you get less of it.

The most powerful weapon that debaters wield against the unwary is causation: marijuana use leads to heroin addiction, pornography to rape, video games to mass murder, high consumption of margarine to divorces in Maine.

By 2000, however, just 46% of the association’s members said minimum-wage laws increased unemployment, largely because of Card and Krueger’s research.

Their findings sparked interest in further research into why a higher minimum wage doesn’t reduce employment. One conclusion is that companies are able to pass on the cost of higher wages to customers by raising prices. In other cases, if a company is a major employer in a particular area, it might have been able to keep wages particularly low up to that point, and therefore would be able to afford to pay a higher minimum wage without cutting jobs. The higher pay would also attract more applicants, boosting labor supply.

“That really surprising evidence on the impact of the minimum wage has shaken up the field at a very fundamental level,” said Arindrajit Dube, an economics professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, who has duplicated and broadened Card and Krueger’s research. “And so for that reason, and all the following research that their work ignited, this is a richly deserved award.”

Krueger, who died in 2019, would almost certainly have shared in the award, Dube said, but the economics Nobel isn’t awarded posthumously.

At least 27 scientists with San Diego ties have won Nobel Prizes. Is there something in the water?

Card’s work also challenged another commonly held idea, that immigrants depress wages for native-born workers. He found that incomes of the native-born can benefit from new immigration, whereas immigrants who arrived earlier are the ones at risk of being negatively affected.

To study the effect of immigration on jobs, Card compared the labor market in Miami in the wake of Cuba’s sudden decision to let people emigrate in 1980, which led 125,000 people to leave in what became known as the Mariel boatlift. It resulted in a 7% increase in Miami’s workforce.

By comparing the evolution of wages and employment in four other cities, Card found no negative effects for Miami residents with low levels of education. Follow-up work showed that increased immigration can have a positive effect on income for people born in the country.

Angrist and Imbens won their half of the award for working out the methodological issues that enable economists to draw solid conclusions about cause and effect even where they cannot carry out studies according to strict scientific methods.

The Philippine government has belatedly congratulated investigative journalist Maria Ressa for winning this year’s Nobel Peace Prize.

Card’s work on the minimum wage is one of the most well-known natural experiments in economics. The problem with such experiments is that it can sometimes be difficult to isolate cause and effect. For example, if you want to figure out whether an extra year of education will increase a person’s income, one seemingly simple method might be to compare the incomes of adults with one more year of schooling with the incomes of those without.

Yet there are many other factors that could determine whether those with an extra year of schooling are able to make more money. Perhaps they are harder or more diligent workers who would have made more money than those without the extra year even if they did not stay in school. These kinds of issues cause economists and other social science researchers to say that “correlation doesn’t prove causation.”

Imbens and Angrist, however, figured out ways to isolate the effects of things such as an extra year of school. Their methods enable researchers to draw much clearer conclusions about cause and effect, even if they are unable to control a factor such as who gets extra education in the same way that scientists in a lab can control their experiments.

Speaking by phone from his home, Imbens told reporters gathered in Stockholm for the Nobel announcement that he had been asleep after “a busy weekend” when the call came in the wee hours in the U.S.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“I was just absolutely stunned then to get a telephone call,” he said. “And then I was just absolutely thrilled to hear the news ... that I got to share this with Josh Angrist and and David Card,” whom he called “both very good friends of mine.” Imbens said Angrist was the best man at his wedding.

The award comes with a gold medal and 10 million Swedish kronor (more than $1.14 million).

Unlike the other Nobel prizes, the economics award wasn’t established in the will of Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel but by the Swedish central bank in his memory in 1968, with the first winner selected a year later. It is the final prize to be announced each year.

Last year’s economics award went to two Stanford University economists who tackled the tricky problem of making auctions run more efficiently.

As a new Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Russian newspaper editor Dmitry Muratov has downplayed the buzz around his name.

It also created an endearing moment when one had to knock on the other’s door in the middle of the night to wake him up and tell him they had won.

Last week, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to journalists Maria Ressa of the Philippines and Dmitry Muratov of Russia for their fight for freedom of expression in countries where reporters have faced persistent attacks, harassment and even murder. Ressa was the only woman honored this year in any category.

The Nobel Prize for literature was awarded to Tanzanian writer Abdulrazak Gurnah, who was recognized for his “uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee.”

The prize for physiology or medicine went to California scientists David Julius of UC San Francisco and Ardem Patapoutian of Scripps Research in La Jolla for their discoveries into how the human body perceives temperature and touch.

Three scientists won the physics prize for work that found order in seeming disorder, helping to explain and predict complex forces of nature, including climate change.

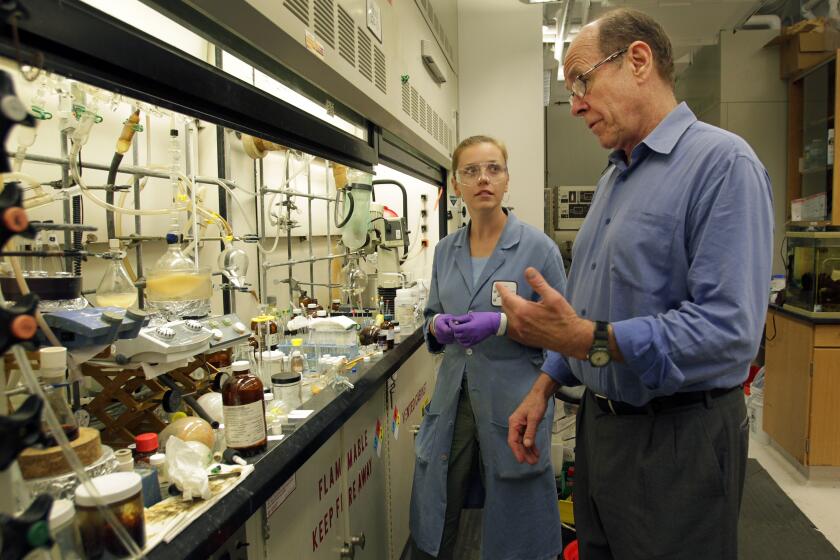

Benjamin List and David W.C. MacMillan won the chemistry prize for finding an easier and environmentally cleaner way to build molecules that can be used to make compounds, including medicines and pesticides.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.