U.N. climate negotiators appear to back off from call to end coal use

- Share via

GLASGOW, Scotland — Negotiators at this year’s United Nations climate change talks in Scotland appeared Friday to be backing away from a call to end all use of coal and to phase out fossil-fuel subsidies completely, but gave poor countries hope for more financial support to cope with global warming.

The latest draft proposals from the meeting’s chair released Friday call on countries to accelerate “the phaseout of unabated coal power and of inefficient subsidies for fossil fuels.”

A previous proposal Wednesday had been stronger, calling on countries to “accelerate the phasing out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuel.” The changes, if agreed, could give countries loopholes to continue burning coal and subsidize fossil fuels.

While the chair’s proposal is likely to undergo further negotiation at the talks, which are due to end Friday, the change in wording suggested a shift away from unconditional demands that some fossil-fuel exporting nations have objected to.

U.S. climate envoy John F. Kerry said Washington backed the current wording. “We’re not talking about eliminating” coal, he told fellow climate diplomats.

On government funds flowing into fossil fuels, Kerry said: “Those subsidies have to go.”

United Nations summit goes into overtime before ending with an agreement in fight against climate change.

“We’re the largest oil and gas producer in the world, and we have some of those subsidies,” he said.

Kerry said it was “a definition of insanity” that trillions of dollars were being spent to subsidize fossil fuels worldwide. “We’re allowing to feed the very problem we’re here to try to cure. It doesn’t make sense.”

There was a mixed response from observers at the talks on how significant the addition of the words “unabated” and “inefficient” was to the new draft proposals.

Richie Merzian, a former Australian climate negotiator who directs the climate and energy program at the Australia Institute think tank, said the additional caveats were “enough that you can run a coal train through it.”

Young activists are coming of age when the effects of the climate crisis are already being felt — foreshadowing a perilous future. They want the United Nations COP26 summit to reduce global warming.

Countries such as Australia and India, the world’s third-biggest emitter, have resisted calls to phase out coal any time soon.

Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg told the Associated Press she feared that, “as long as our main goal is to find loopholes and find excuses, not to take real action, then we will most likely not see any big results in this meeting.”

Thunberg, who attended the start of the talks in Glasgow, spoke at her weekly protest outside Sweden’s parliament Friday morning.

Helen Mountford, a senior climate expert at the World Resources Institute, said allowing countries to determine which subsidies they consider inefficient would water down the agreement.

What nations have promised varies. Some have pledged to quit coal completely at a future date, while others say they’ll stop building new plants.

“It definitely weakens it,” she said.

Even so, the explicit reference to ending at least some state support for oil, gas and coal offered “a strong hook for phasing out fossil fuels subsidies, so its good to have it in there,” she said.

The question of how to address the continued use of fossil fuels responsible for much of global warming has been one of the key sticking points at the two-week talks.

Scientists agree it is necessary to end their use as soon as possible to meet the 2015 Paris accord’s ambitious goal of capping global warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit). But explicitly including such a call in the overarching declaration is politically sensitive, including for countries, such as Saudi Arabia, that fear oil and gas may be targeted next.

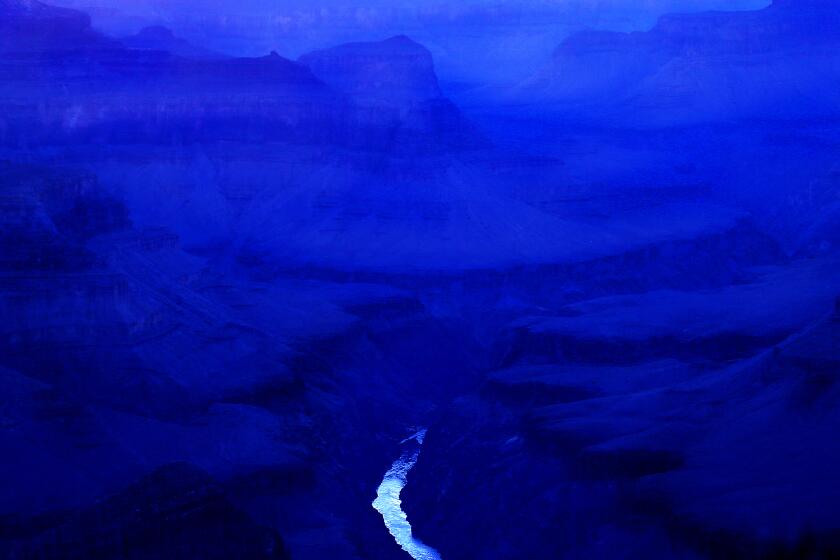

To water resiliency advocates at the U.N. climate conference, the Colorado River stands out as ‘the best example globally of how things can go badly.’

Another crunch issue is the question of financial aid for poor countries to cope with climate change. Rich nations failed to provide them with $100 billion annually by 2020, as agreed, causing considerable anger among developing countries going into the talks.

The latest draft reflects those concerns, expressing “deep regret” that the $100-billion goal hasn’t been met and urging rich countries to scale up their funding.

It also adds wording that could create a fund to compensate countries for serious destruction resulting from climate change. Rich nations such as the United States, which have historically been the biggest source of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, are opposed to any legal obligation to compensate poor countries.

Discussion of the issue, known as “loss and damage,” is likely to go to the wire, negotiators said.

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Environmental campaigners expressed concerns about possible loopholes in agreements for international cooperation on emissions reduction, which includes the rules for carbon markets. Businesses are particularly keen to balance out excess emissions by paying others not to emit a similar amount.

“The invitation to greenwash through carbon offsetting risks making a farce of the Paris agreement,” said Louisa Casson of Greenpeace. “If this goes ahead, governments are giving big polluters a free pass to pollute under the guise of being ‘carbon neutral,’ without actually having to reduce emissions.”

Negotiators from almost 200 nations gathered in Glasgow on Oct. 31 amid dire warnings from leaders, activists and scientists that not enough is being done to curb global warming.

According to the proposed decision, countries plan to express “alarm and utmost concern” that human activities have already caused around 1.1 degrees Celsius (2 degrees Fahrenheit) of global warming “and that impacts are already being felt in every region.”

A hazy fog that stubbornly refused to burn away puzzled residents across the region last weekend. The experts make sense of it.

While the Paris accord calls for limiting temperature to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit), and ideally no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit), by the end of the century compared to pre-industrial times, the draft agreement notes that the lower threshold “would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change” and resolves to aim for that target.

U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres told the Associated Press this week that the 1.5 degrees Celsius “is still in reach but on life support.”

If negotiators are unable to reach agreement by Friday’s official deadline, it is likely the talks will go into overtime. This has happened at many of the previous 25 meetings, as consensus among all 197 countries is required to pass decisions.

The annual meetings, first held in 1995 and skipped only once last year, because of the pandemic, are designed to get all countries to gradually ratchet up their efforts to curb global warming.

But for many vulnerable nations, the process has been far too slow.

“We need to deliver and take action now,” said Seve Paeniu, the finance minister of the Pacific island nation of Tuvalu. “It’s a matter of life and survival for many of us.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.