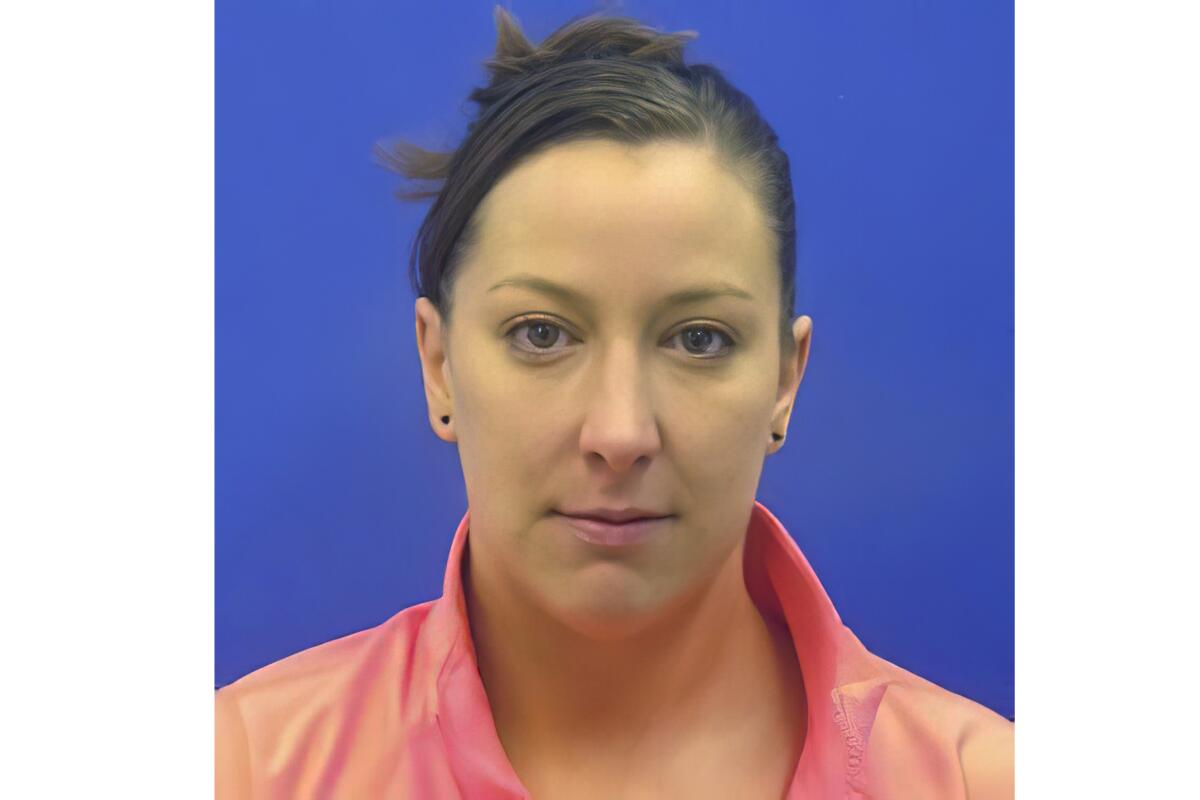

San Diego’s Ashli Babbitt a martyr? Her past tells a more complex story

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The first time Celeste Norris laid eyes on Ashli Babbitt, the future insurrectionist from San Diego had just rammed Norris’ vehicle three times with an SUV and was pounding on the window, challenging her to a fight.

Norris says the bad blood between them began in 2015, when Babbitt engaged in a months-long extramarital affair with Norris’ longtime live-in boyfriend. When she learned of the relationship, Norris called Babbitt’s husband and told him she was cheating.

“She pulls up yelling and screaming,” Norris said in an exclusive interview with the Associated Press, recounting the July 29, 2016, road-rage incident in Prince Frederick, Md. “It took me a good 30 seconds to figure out who she was. … Just all sorts of expletives, telling me to get out of the car, that she was going to beat my ass.”

Babbitt was later charged with numerous misdemeanors.

The attack on Norris is an example of erratic and sometimes threatening behavior by Babbitt, who was shot by a police officer while at the vanguard of the Jan. 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol. Former President Trump and his supporters have sought to portray her as a righteous martyr who was unjustly killed. The officer who shot her was cleared of any wrongdoing by two federal investigations.

But the life of the Air Force veteran from California who died while wearing a Trump campaign flag wrapped around her shoulders like a cape, was far more complicated than the heroic portrait presented by Trump and his allies.

Air Force veteran Ashli Babbitt opined on gun laws and border security on social media, then bought into QAnon conspiracy theories before joining pro-Trump insurrectionists to storm the U.S. Capitol, where she was shot dead by police.

In the months before her death, Babbitt had become consumed by pro-Trump conspiracy theories and posted angry screeds on social media. She also had a history of making violent threats.

Babbitt, 35, was fatally shot while attempting to climb through the broken window of a barricaded door leading to the Speaker’s Lobby inside the Capitol, where police officers were evacuating members of Congress from the mob supporting Trump’s false claim that the 2020 presidential election was stolen.

Her husband, Aaron, declined to comment in October when a reporter knocked on the door of the San Diego apartment he shared with Ashli and another woman. In a June interview with Tucker Carlson of Fox News, Babbitt said he has been sickened by some of what he has seen written about his deceased wife.

“There’s never been a person who Ashli ran across in her daily life that didn’t love her,” said Babbitt, 40.

That is not how Norris viewed her.

Court records involving the 2016 violent confrontation between Babbitt and Norris have previously been reported by media outlets, including the AP. But Norris, now 39, agreed to speak about it publicly for the first time in an interview with the AP and shared previously unreported details. She also provided documents and photos from the crash scene to support her account.

Norris was in a six-year relationship with Aaron Babbitt when she said she learned he was cheating on her with a married co-worker from his job as a security guard at a nuclear power plant near the Chesapeake Bay. She eventually found out the other woman was Ashli McEntee, who at the time went by the last name of her then-husband.

Norris said she tried for a few months to salvage her relationship with Aaron Babbitt before finally deciding to move out of their house. Within days, Norris said, Ashli moved in.

A few weeks later, Norris was waiting at a stop sign in Prince Frederick, about an hour southeast of Washington, D.C., when she says a white Ford Explorer passed her going the other direction.

Norris saw the SUV pulling a U-turn before speeding up behind her. She recounts that the SUV’s driver began swerving erratically, laying on the horn and attempting to pass a Chevrolet Suburban that was in between them on the narrow two-lane road.

When the driver of the Chevy pulled over, Norris said the white Ford SUV accelerated and rammed into her rear bumper. She said the SUV rammed her a second time and then a third, all while the vehicles continued to roll down the road.

After Norris dialed 911, an emergency dispatcher advised her to pull over to the shoulder and stop. As she waited for help, Babbitt got out of her vehicle and came up to Norris’ driver’s-side window, banging on the glass.

A case report from the Calvert County Sheriff’s Office obtained by the AP shows Ashli Babbitt was issued a criminal summons on charges of reckless endangerment, a misdemeanor punishable by up to five years in prison and a $5,000 fine. She was also charged with malicious destruction of property for the damage to Norris’ vehicle.

Court records show those charges were later updated to include traffic offenses — reckless driving, negligent driving and failure to control a vehicle’s speed to avoid a collision.

Photos from the scene provided to the AP by Norris show Babbitt’s white Ford Explorer with its front bumper smashed in. The SUV’s grill is also pushed in and the hood dented. The rear bumper of Norris’ Escape is pushed in on the passenger side, with the detached Maryland license plate from the front bumper of Babbitt’s SUV wedged into it.

Norris later got a judicial order that barred Ashli Babbitt from attempting to contact Norris, committing further acts of violence against her and going to her home or workplace.

In the weeks after the incident, Norris said Babbitt falsely claimed to authorities that the collisions had occurred when Norris repeatedly backed her vehicle into Babbitt’s SUV. But when the case went to trial, Norris said, Babbitt changed her story, admitting under oath that she had collided with Norris’ vehicle but portraying it as an accident.

No transcript from the hearing was available, but Norris said the lawyer defending Babbitt made repeated references to her employment at the local nuclear power plant and years of military service, which included deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. A judge acquitted Babbitt on the criminal charges.

In February 2017, records show Norris asked for and received a second peace order against Ashli Babbitt, citing ongoing harassment and stalking.

“I lived in fear because I didn’t know what she was capable of,” Norris told the AP. “I was constantly looking over my shoulder.”

In 2019, Norris filed a personal injury lawsuit against Ashli Babbitt, seeking $74,500 in damages, and she said she settled out of court with Babbitt’s insurance carrier for an undisclosed sum.

By then, Aaron and Ashli had moved to California, where she grew up and still had family.

Associated Press writer Elliot Spagat in San Diego contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.