- Share via

Chinese leader Xi Jinping views the Olympic Games — he has pored over venue blueprints and been involved in every aspect of planning — as a validation not only of his statecraft but also of the rise of a confident, economically robust nation that is rearranging the world order.

Beijing’s second Olympics, opening this week amid the world’s strictest COVID-19 controls, mass incarceration of minorities in Xinjiang, military threats to Taiwan and the dismantling of civil rights in Hong Kong, are a statement of defiance. They are a declaration that Xi’s Communist Party no longer needs the acceptance of the West at a time when much of the planet is beholden to a patriotic and powerful China.

“The world is turning to China, and China is ready,” Xi said in a video address to an International Olympic Committee session Thursday.

Much has changed since China sought to impress the globe when it hosted the stunningly choreographed 2008 Summer Olympics. Ai Weiwei, the artist who designed the “Bird’s Nest” stadium for that event, is now a dissident in exile. Foreign press have been expelled, detained and harassed with increasing intensity. Many of the young Hong Kongers who cheered for Chinese athletes in 2008 became protesters in 2019; they are now under arrest or have fled abroad amid the city’s relentless purging of freedoms.

The United States and several other democratic countries have imposed a diplomatic boycott of the Games. Officials from other nations are staying away for pandemic reasons. Fewer than 30 state leaders and royals are expected to travel to Beijing versus more than 80 in 2008.

Many of the leaders who will appear at the opening ceremony are from autocratic countries, including Russian President Vladimir Putin, who is expected to meet with Chinese counterpart Xi and discuss security concerns in Europe as Russia masses troops near the Ukrainian border. The talks between the two are another indication of China’s rise and Xi’s determination to recast the world order away from U.S. and European designs.

No foreign spectators will be in the stands. No domestic tickets have been sold. Only state-approved, preselected audiences will fill the venues, including those for figure skating and hockey. All athletes, trainers, media and other Olympics attendees will live in a tightly controlled “closed loop” with no access to the rest of China, or even Beijing.

For Xi, the Games are a personal project — he even inspected the construction of the ski slopes — whose success will lead to his expected third term in power in the fall. That would give him more control over China’s future than any leader since Deng Xiaoping, who instituted term limits in the 1980s as guardrails against the one-man rule that devastated China under Mao Zedong.

Xi has eliminated potential opposition through internal crackdowns. He has crushed civil society and harnessed all groups with organizing power within China. A successful Beijing Winter Olympics would offer international affirmation of Xi’s style of rule. He could point to it as proof that, despite his flouting of party norms, his nationalistic vision and tight control over everything, including the housing market and the number of warships in the South China Sea, has made his nation a force the world must recognize.

Xi’s top-down style of rule is resonant in China’s strict coronavirus lockdowns and widespread testing that kept infection numbers low even as surges swept the planet. State propaganda about the nation’s coronavirus strategy is not a discussion about public health but an aggrandizement of the ideological and systemic triumph that proves, at least in the party’s eyes, China’s superiority over the West.

But there are risks to Xi’s statecraft. As the Games begin this week, with China’s middle class restive and its economy slowing, the mood in Beijing is less excitement than exhaustion. For the third year in a row, COVID-19 travel restrictions have meant that most people are not returning to their hometowns for family reunions during the Lunar New Year, usually China’s biggest holiday.

Sudden, extreme lockdowns affecting tens of millions of people have become increasingly frequent as the more infectious Omicron and Delta variants spread — and as officials fear losing their jobs for allowing outbreaks in their cities. Residents of Xian recently raised an outcry over being trapped in their homes and unable to get food during a citywide lockdown.

A woman in Xian who was eight months pregnant miscarried after a hospital refused her entry until after she tested negative for the virus. Images of her bleeding on the street went viral, sparking public anger and an eventual notice from the city government that hospitals should not let COVID prevention affect regular treatment of patients.

These were brutal but familiar scenes, reminiscent of the individual tragedies that played out under extreme lockdown in Wuhan at the pandemic’s beginning. Yet because China has already celebrated its victory over the virus and promoted the party’s zero-COVID strategy — under Xi’s leadership — there is little appetite for dwelling on the government’s missteps.

Beijing has similarly insisted on going forward with the Olympics despite potential outbreaks, human rights protests and political drama, notably a dissident’s viral plea or an athlete speaking out against China’s abuses. At work in the capital, where guards patrol the perimeter of the fenced-in Games bubble, is a Xi-era focus on stability and control, which in the coming weeks will be aided by the IOC and the Olympics’ international corporate sponsors.

The capital’s residents are under particular pressure to stay home, avoid gatherings, and even delay package deliveries from outside the city until the Olympics are over. Most people will watch the Games at home. That will prevent virus spread and any protests or unwanted contact between Chinese citizens and foreigners with dangerous ideas.

Many Chinese dissidents have had their social media deactivated and probably will be forced to “travel” with state security agents for the duration of the Games. Last month a Beijing 2022 official warned that athletes who engage in “any behavior or speech that is against the Olympic spirit, especially against the Chinese laws and regulations,” would face “certain punishment.” That could include cancellation of accreditation, he said, or other unspecified consequences.

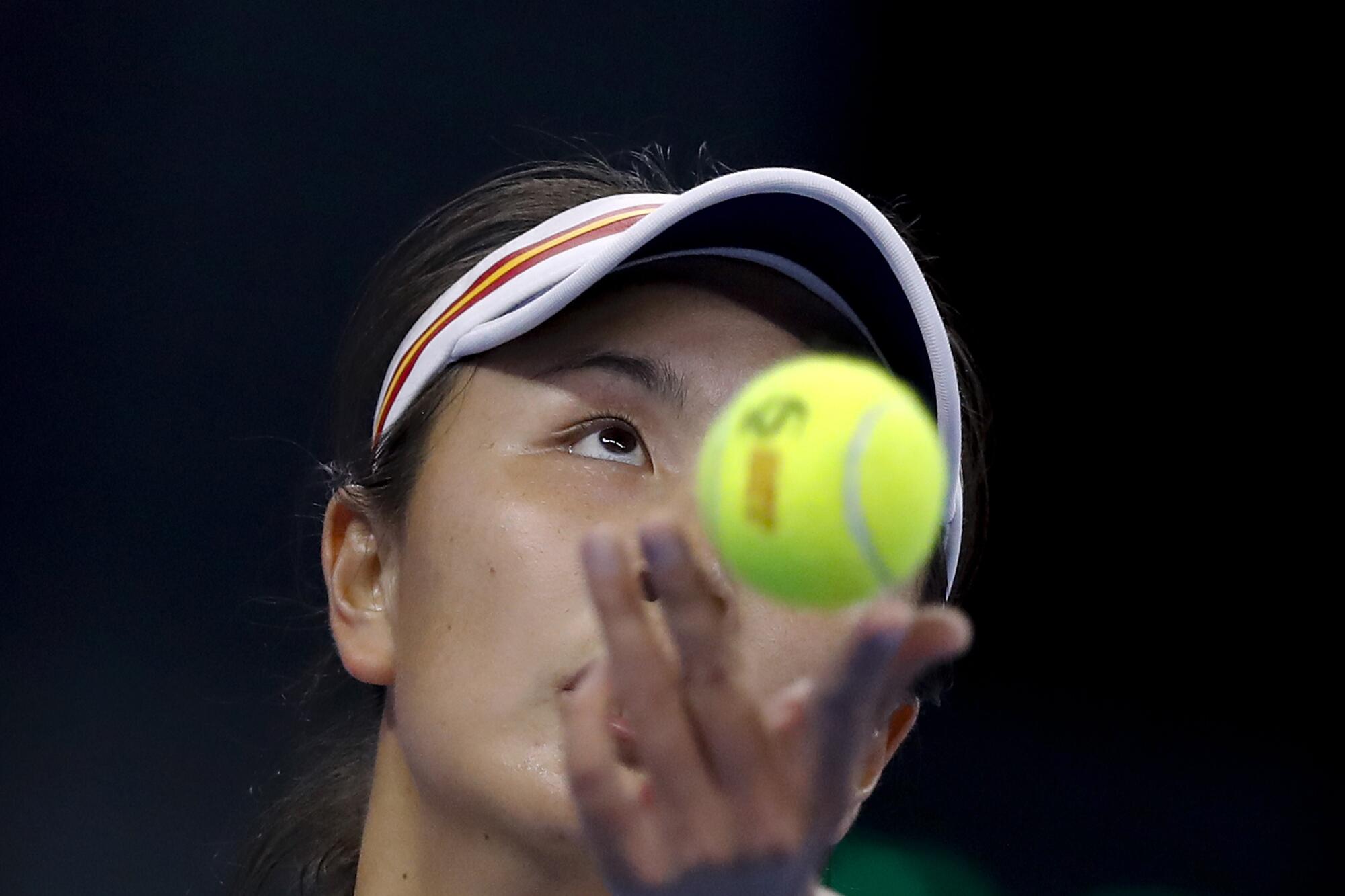

In November, prominent tennis player Peng Shuai was censored online and disappeared from public view after making sexual assault allegations against a high-ranking Communist Party official. Women’s tennis players and sport leaders called for an investigation.

State media responded with photos and videos of Peng and a purported email from her saying she was fine. The IOC then released images of a video call its president, Thomas Bach, held with Peng and said she appeared to be safe, drawing criticism from human rights groups that they were collaborating with the Chinese state.

On Thursday, Bach said Peng would enter the Olympics bubble to meet with him, and that he would not press for an inquiry into her assault allegations unless she asked for it. “It’s her life,” he said.

The IOC has refused to meet with the Coalition to End Forced Labor in the Uyghur Region, a human rights group raising concerns about whether the Beijing Games’ official merchandise is made with forced labor from Xinjiang. Companies sponsoring the Games, including Airbnb, Allianz, Coca-Cola, Intel, P&G, Toyota and Visa have avoided repeated questions from media and human rights groups over China’s widespread human rights violations.

But Xi and the party have scripted every detail and left little to chance. All this has emboldened China to act more confidently, even if the country, which is relatively new to highly competitive winter sports, is not expected to win many gold medals.

As the torch relay began this week, state media celebrated that one of the torchbearers was a People’s Liberation Army soldier who survived a deadly border clash with Indian soldiers in 2020. The Global Times, a state-run tabloid, called the soldier a “hero.” India announced Thursday that its top diplomat in Beijing would not attend the opening or closing ceremonies as a result, although one Indian skier is still competing.

“It is indeed regrettable that the Chinese side has chosen to politicize an event like the Olympics,” said Indian Foreign Ministry spokesman Arindam Bagchi at a news briefing.

The opening ceremony has also become a political tinderbox for Taiwan’s Olympic team, which has been pressured into competing under the name “Chinese Taipei” due to Chinese claims of sovereignty over the democratic island. Taiwan’s team said last week that it would not attend the opening or closing ceremonies. But it has since announced that it would attend to meet IOC requirements.

The South China Morning Post reported this week that China had pressured the United Nations human rights commission into delaying the release of a report on China’s rights violations against Uyghurs and other minorities in Xinjiang until after the Olympics.

The newspaper also reported that China had agreed to host the U.N. human rights chief, who has been seeking access to Xinjiang for an independent investigation since 2018 — but only for a “friendly” visit, and only after the Olympics.

Xi said at a recent IOC session that “China is ready” to deliver a “streamlined, safe and splendid Games.”

Bach, the IOC chief, noted he has been worried since 2020 about the “dark clouds of the growing politicization of sport.”

“The boycott ghosts of the past were rearing their ugly heads again,” he said. But the IOC had managed to pull global leaders together for a “unifying” Olympics that would also create major commercial opportunities for the winter sports industry, especially companies eager to sell to China.

Bach said he was happy and proud that the Games would go on.

So was Xi.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.