- Share via

WASHINGTON — Johana Medina Leon spent years advocating for the LGBTQ community and HIV awareness before fleeing the violence she faced as a transgender woman in El Salvador. The 25-year-old nurse technician had hoped to start a new life in California.

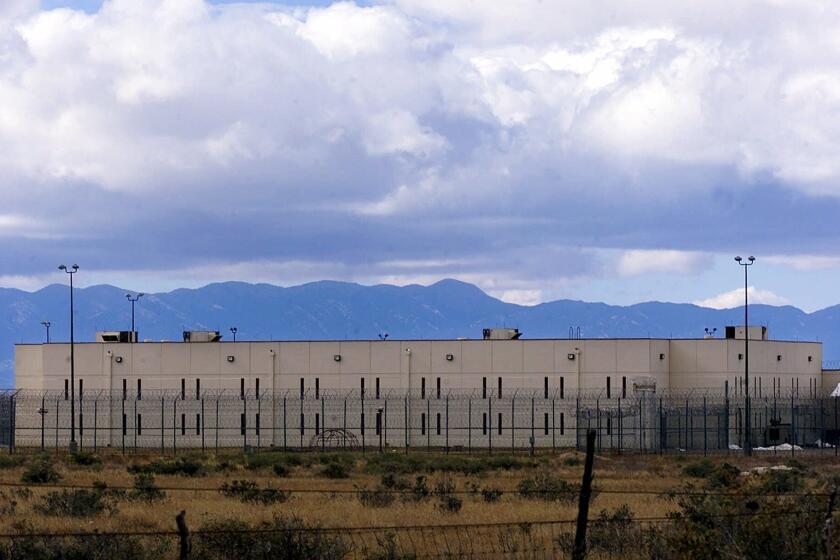

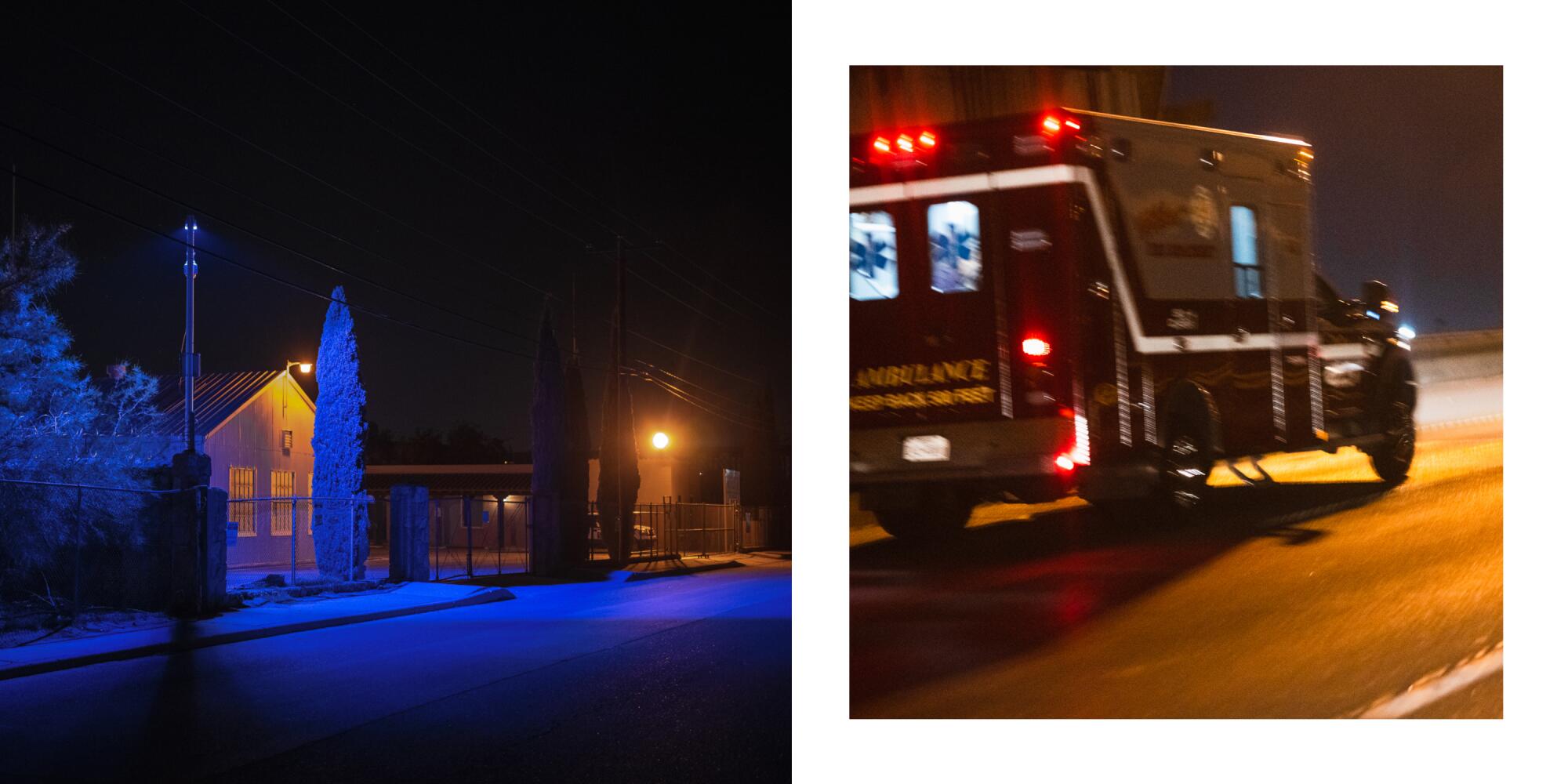

But just over a month after she was detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and booked into New Mexico’s Otero County Processing Center, her health was in free-fall. She was transferred to an El Paso hospital, where she died on June 1, 2019.

For the record:

2:28 p.m. May 19, 2022An earlier version of this story quoted Dale Melchert as saying that had the government provided Roxsana Hernandez “with the care she was entitled to within 12 hours of custody, she would be here today.” Melchert said that had the government provided Roxsana Hernandez “with the care she was entitled to within 12 hours of custody, she could be here today.”

8:28 a.m. May 14, 2022An earlier version of this story said that Roxsana Hernandez’s HIV status went undiagnosed throughout her detention until her condition worsened. Her HIV went untreated throughout her detention until her condition worsened. It also said that Hernandez never received an intake medical screening. Hernandez did not receive an intake medical screening until three days after she was detained by ICE, though the agency’s policy requires screening within 12 hours of arrival.

Medina Leon’s name wasn’t among the nine deaths recorded by ICE that year. She had been hurriedly released from custody while hospitalized, just before succumbing to the same failures in care she had worked to prevent for others.

The circumstances surrounding Medina Leon’s release and death were discovered among more than 16,000 pages of documents disclosed as part of an ongoing lawsuit brought by The Times against the U.S. Department of Homeland Security seeking records of abuse at immigration detention centers. The documents provide a rare look into one of several known instances in which detainees were discharged on the edge of death, underscoring long-standing complaints from advocates about uncounted deaths of people who have been in ICE custody.

Medina Leon’s case was investigated by the DHS Office of Inspector General, a watchdog agency with oversight of ICE that has recently come under fire from transparency advocates for how it handles investigations.

The L.A. Times will sue for records relating to detention centers run by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

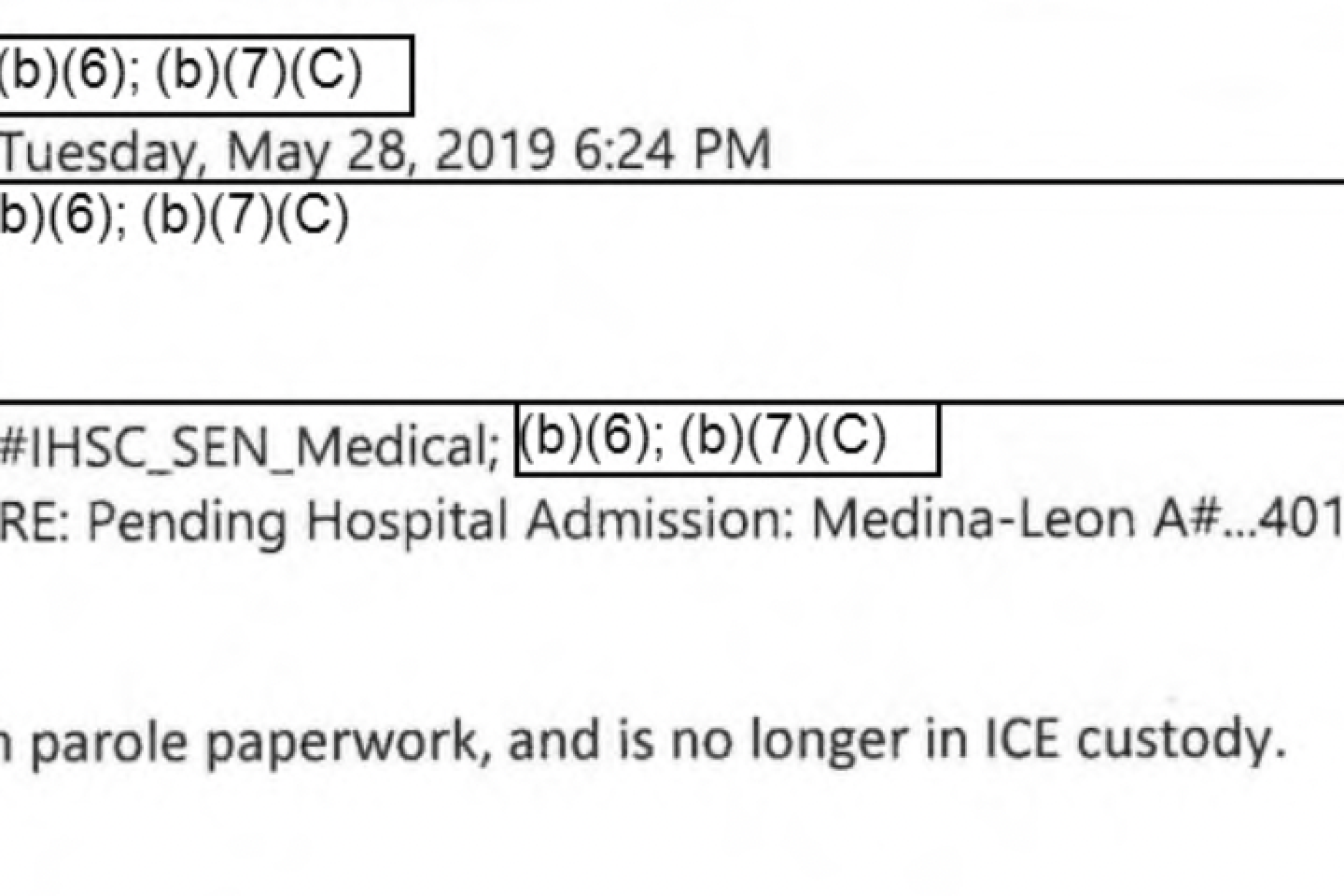

Emails reviewed by The Times show immigration officials moved with unusual speed to remove Medina Leon from custody. While it took six weeks and several visits with medical staff before she saw a doctor in detention, ICE expedited her release in less than six hours — relieving the agency of responsibility when she died four days later.

Los documentos ofrecen una mirada poco común a uno de los varios casos conocidos en los que los detenidos del ICE fueron dados de alta cuando estaban al borde de la muerte.

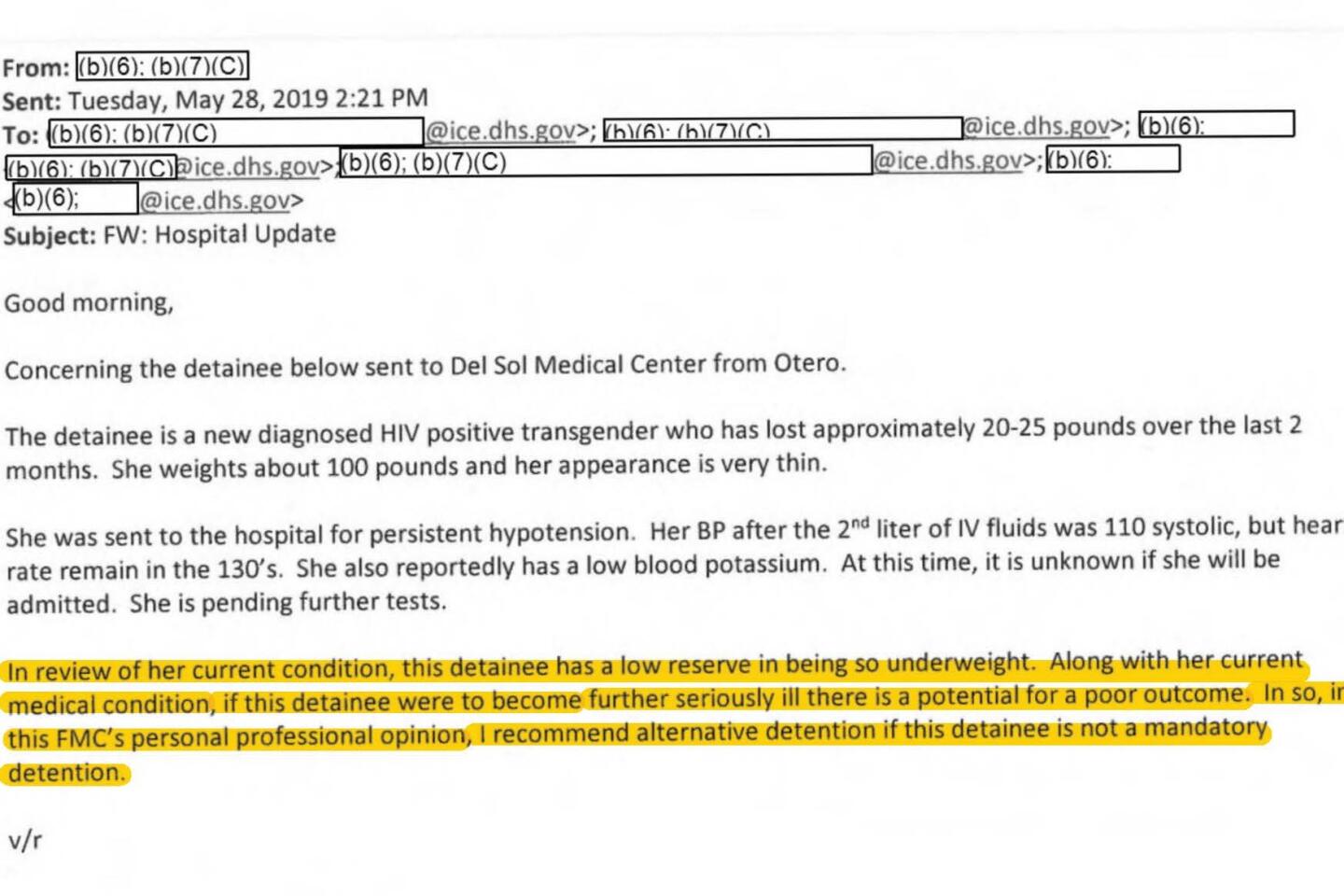

ICE’s field medical coordinator initiated the rapid-fire process on May 28, recommending Medina Leon’s release from Otero. The facility is operated by Management and Training Corp., a private prison company known as MTC.

“If this detainee were to become further seriously ill there is a potential for a poor outcome,” the official wrote, noting that Medina Leon was “so underweight.”

In an email the same day marked “high” importance, another ICE official replied that her “vitals do not look good.”

“Could we please get detainee property for full release ready ASAP,” a detention supervisor responded.

Within hours of her being admitted to the hospital, two ICE agents arrived at Medina Leon’s bed with parole paperwork for her to sign. One of the agents later told investigators that the process was being expedited though he “was not aware of the reasons for the rush.” He said he had never before served release documents at a hospital.

The Department of Homeland Security Inspector General’s office issues an alert calling for detainees to be relocated until conditions improve.

That night, a status update noted Medina Leon’s condition was “serious/critical.” A final email came 20 minutes later: “The detainee has been served with parole paperwork, and is no longer in ICE custody.”

ICE spokeswoman Paige Hughes declined to comment on Medina Leon’s case, but wrote in a statement that the agency “takes very seriously the health, safety, and welfare of those in our care, including those who come into ICE custody with prior medical conditions or who have never before received appropriate medical evaluation or care.”

MTC spokesman David Martinson also declined to comment on the case.

“We take the medical care of detainees very seriously,” he wrote in a statement, adding that “detainees have access to appropriate and necessary medical, dental, and mental health care, including emergency services.”

A Times investigation found that since 2017, at least 265 calls have reported violence and abuse inside California’s four privately run immigrant detention centers. Half of them alleged sex crimes against detainees.

The swift processing of Medina Leon’s parole was highly unusual — such reprieves typically take several days or weeks. During the Trump administration, ICE more often released detainees on bond, which requires families to front thousands of dollars to help loved ones avoid remaining in detention for months as they await decisions on their immigration cases. Others were released under different discretionary orders of recognizance or supervision while their case was pending.

Advocates for detainees say Medina Leon’s death highlights a history of actions by ICE officials that allow the agency to avoid responsibility for sick or dying detainees. ICE has long been criticized for inadequate medical care provided by detention facilities, most of which are managed by for-profit companies like MTC.

Do you have a tip?

Do you know someone who was released from ICE detention with an advanced illness or just before they died? Share your tips about the immigrant detention system with reporters Andrea Castillo and Jie Jenny Zou.

[email protected]

[email protected]

After the first private prison contract was granted in 1983 for a Texas facility, the federal government’s immigrant detention network expanded until it peaked in 2019 with an average daily population of more than 55,000. So far this year, that figure is around 20,000. Nearly 80% of detainees are held in for-profit facilities, though the Biden administration has closed or scaled back several troubled facilities and has favored alternatives such as using ankle monitors to track those awaiting immigration court proceedings.

Despite detaining hundreds of thousands of people nationwide, ICE has said that fewer than a dozen detainees die in custody each year. Recorded deaths have remained low even during the pandemic. ICE reported a high of 21 deaths in 2020 and just five for all of 2021. No deaths have been recorded so far in 2022.

The agency began recording in-custody deaths in 2009 as part of reforms during the Obama administration. That same year, ICE officials admitted they had failed to disclose 10 additional deaths in a list of 90 that the agency delivered to Congress. In 2018, Congress required ICE to publicly release reports on every in-custody death within 90 days. But ICE has failed to comply since the mandate began, according to a September 2020 congressional oversight report.

Why is ICE choosing to release people from custody who are on their deathbeds while they’re hospitalized?

— Eunice Cho, an attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union is suing ICE for access to records about deaths of detainees who were released from custody in their final days after experiencing medical emergencies. The lawsuit names four people — Medina Leon and three men who were released while they were hospitalized and had fallen into comas.

“Why is ICE choosing to release people from custody who are on their deathbeds while they’re hospitalized?” said Eunice Cho, an attorney at the ACLU. “The impact is, of course, that ICE is then exempt from reporting requirements, investigation requirements and financial requirements from the deaths that have taken place” as a result of inadequate healthcare.

‘We wanted to change the world’

For nearly a decade, Medina Leon volunteered for Alexia Sanchez’s advocacy organization, Gay Sin Fronteras, in El Salvador.

Sanchez said Medina Leon accompanied queer and transgender people to medical appointments and pharmacies. She talked people out of acting on thoughts of suicide. And she made hospital visits to ensure that doctors treated patients with HIV, which is heavily stigmatized in El Salvador. Advocates say more than 500 trans people have been killed there since 1995.

The friends saw each other regularly until Medina Leon stopped showing up at organizing efforts. Sanchez, who is also trans, fled months later and now lives in Los Angeles.

U.S. immigration officials report few deaths in custody each year. But if a person is released just before death, ICE doesn’t need to report it.

“We wanted to change the world,” Sanchez said. “Knowing what happened to Johana was a very tough blow.”

After presenting herself to border officials near El Paso and requesting asylum, Medina Leon was transferred on April 14, 2019, to the Otero County Processing Center. Like most immigrants detained by ICE, she had no criminal record.

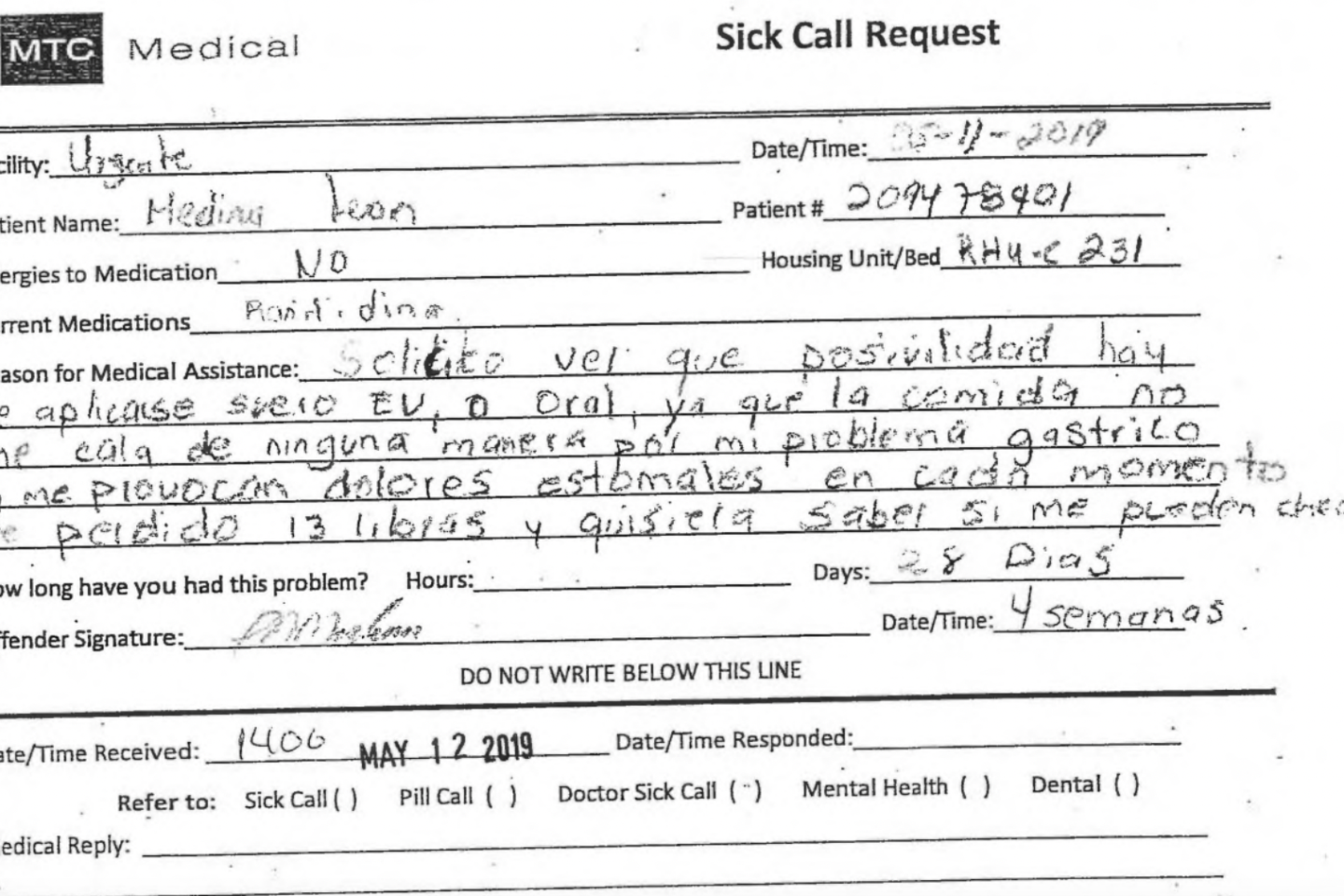

Two days into her stay at Otero, Medina Leon made the first of at least five requests for medical attention, often complaining of stomach pain, vomiting and nausea. Homeland Security Department records reviewed by The Times show nurses prescribed antacids, attributing her condition to the facility’s “spicy food” and a prior history of gastrointestinal issues.

Medina Leon marked the top of each handwritten request “urgent.”

“I can’t keep down the food in any way because of my gastric issue and it gives me constant stomach pain,” she wrote on May 11. “I’ve lost 13 pounds and would like to know if I can be seen.”

By Memorial Day weekend — five weeks into her detention — Medina Leon had lost nearly 18% of her body weight, going from 126 to 103 pounds. Her final request, inquiring about a rash that had developed on her forehead, appeared more desperate: “Urgent please.”

A nurse flagged her case as “serious,” jotting down a growing list of symptoms that now included weakness, a sore throat, cough and acid reflux. She referred Medina Leon for a follow-up appointment with Otero’s on-call nurse practitioner, but he never saw her.

A wrongful-death lawsuit filed by Medina Leon’s family claims that another medical request she made the next day went unanswered. MTC policy requires medical staff to review requests within a day — or immediately in urgent situations. Staff then have another 24 hours to evaluate sick detainees in person.

In depositions, nurses who treated Medina Leon said that, at the time, Otero staff relied on a paper system to refer detainees’ medical requests to providers. Under that system, one staffer testified, it could take “a couple days” for a provider to respond to a referral.

A nurse practitioner who was supposed to treat Medina Leon on May 24 told inspector general investigators that he had not heard about her case. Two days later, when he called to check in on patients during his next scheduled shift, he was told “nothing exciting was awaiting.”

Del Sol Medical Center in El Paso.

The nurse practitioner, who spent just a few days a week at Otero, also had a full-time job at a clinic and owned a restaurant, according to a deposition transcript. He admitted in his testimony that he never saw Medina Leon in person.

In a separate deposition, Otero’s warden acknowledged the nurse practitioner had violated MTC’s company policy by stamping his name on Medina Leon’s medical record without actually seeing her.

By the time Medina Leon saw a doctor on May 27, her skin had yellowed, her temperature was fluctuating and her heart struggled to pump blood. Unsure of what was causing her rapid decline, staff ordered tests for hepatitis, HIV and chickenpox.

The next morning, the wrongful-death lawsuit claims, Medina Leon was found unconscious in her cell. Inspector general records show she had been dizzy, threw up her breakfast and complained of chest pains.

Sanchez said Medina Leon had always radiated optimism, frequently telling friends, “Everything is possible.” But when her HIV test came back positive May 28, she grew distraught, covered her face and cried, a staffer told investigators.

Within hours, an ambulance was called to rush Medina Leon to Del Sol Medical Center in El Paso. Staff waited by her side with a defibrillator in case her heart gave out.

As word of Medina Leon’s plummet spread, ICE officials moved swiftly to process her parole.

Four days later she was dead.

A death certificate listed sepsis — a life-threatening condition that arises when the body struggles to fight an infection — as the primary cause of death, with pneumonia and HIV as underlying causes. A private autopsy ordered for the family’s lawsuit found a blood clot in Medina Leon’s lungs and a fungal infection that had spread to multiple organs.

An ICE statement at the time said her death was “another unfortunate example of an alien who enters the United States with an untreated, unscreened medical condition.”

But behind the scenes, officials at the inspector general’s office and ICE had begun an internal investigation that would lead to more questions than answers.

Medical staff involved in her care agreed more could have been done sooner, though they disagreed over who or what was at fault. The doctor who rushed Medina Leon to the hospital told investigators he thought someone should have phoned him earlier because he was on call 24 hours a day. Meanwhile, a nurse told investigators that company protocol allowed emergency calls only for patients in “acute distress.”

Accounts also differ as to Medina Leon’s awareness of her HIV status. One nurse told investigators Medina Leon said she might have HIV, mentioning that she was stuck by a dirty needle while working as a nurse in El Salvador a year earlier. But the doctor who treated her ordered the HIV test as part of a slate of exams that included chickenpox and syphilis. And ICE’s medical coordinator said Medina Leon denied any history of known HIV exposure when they spoke at the hospital.

Under ICE policy, detainees receive comprehensive health assessments within two weeks of being booked into a facility. But staff at the Otero detention center told investigators that lab tests are not standard and are typically ordered by doctors in specific cases for certain preexisting conditions. ICE doesn’t proactively screen detainees for HIV.

ICE’s own medical experts had warned the agency about patients like Medina Leon. Two months before her death, the same medical coordinator who recommended Medina Leon’s release suggested the agency begin treating transgender detainees as “chronic” patients in order to facilitate earlier diagnoses.

¿Tienes una historia?

¿Conoce a alguien que fue liberado de la detención de ICE con una enfermedad avanzada o justo antes de morir? Comparta sus historias sobre el sistema de detención de inmigrantes con las reporteras Andrea Castillo y Jie Jenny Zou.

[email protected]

[email protected]

The coordinator had also flagged several healthcare deficiencies at Otero. Among the issues: Detainees with identified chronic conditions weren’t evaluated quickly enough, the level of urgency for cases wasn’t documented by providers in referrals to outside specialists, and detainees arriving with prescribed medications were “not having their medications continued.”

Despite a slew of unresolved questions, investigators closed their case on Medina Leon’s death in September 2020, concluding there was no “evidence of malfeasance or policy violations.” Aside from the ICE medical coordinator who recommended her release, Medina Leon’s entire medical team of more than seven people was employed by private contractor MTC.

In an email, the Office of Inspector General stood behind its investigation, which found “no misconduct by DHS staff or contractor personnel.” Officials declined to explain the decision to investigate Medina Leon’s death, but noted that it was one of two ICE out-of-custody deaths reviewed by the agency since 2003.

ICE spokeswoman Hughes noted that the agency’s policy of reviewing detainee deaths was updated in October 2021 to include deaths that occur within a month of release from custody “when appropriate, to ensure accountability and maximum transparency.”

‘A death sentence’

Healthcare experts say deaths like Medina Leon’s are avoidable.

“Young women don’t have to die of sepsis, for God’s sake,” said Coleen Kivlahan, medical director of the human rights asylum clinic at UC San Francisco. “Was this death preventable by early screening and early care? The answer would be yes.”

Kivlahan said any medical provider with experience treating trans patients would have checked for HIV early on, particularly in cases of severe weight loss. Many of the trans patients she sees in her clinic — who are seeking asylum in the U.S. after trauma and abuse in their home countries — are HIV-positive, but go largely undiagnosed while in detention.

Activists quickly sounded the alarm about Medina Leon’s death in 2019, noting its striking similarities to that of another trans woman who died in ICE custody a year earlier.

As with Medina Leon, Roxsana Hernandez’s HIV went untreated throughout her detention until her condition worsened, landing her in the hospital in 2018. She died of dehydration and complications from HIV less than a month after arriving at the Tijuana border from Honduras and requesting asylum. Hernandez did not receive an intake medical screening until three days after she was detained by ICE, though the agency’s policy requires screening within 12 hours of arrival, said Dale Melchert, who led a wrongful-death lawsuit for the Transgender Law Center. She was transferred to a different facility three times in three days.

Unlike with Medina Leon, Hernandez’s death was officially recorded by ICE, requiring the agency to notify Congress and disclose some records.

Both women made repeated requests for medical attention as they experienced telltale signs of untreated HIV: weight loss, yellowing skin, fever and disorientation.

“In both Roxsana and Johana’s cases, treatable medical conditions became a death sentence,” Melchert said. Had the government provided Hernandez “with the care she was entitled to within 12 hours of custody, she could be here today,” he said.

An ACLU attorney said the case raises questions about whether immigration officials are undercounting detainee deaths during the pandemic by releasing people just before they die.

Watchdog groups have urged Congress to investigate and publicize death reviews for people released from immigration custody just before they die, including during a 2019 House committee hearing on oversight of ICE detention three months after Medina Leon’s death.

Advocates say quantifying how many cases like Medina Leon’s exist is difficult because ICE has historically refused to provide basic information about detainees who die just after being released from custody. In addition to Medina Leon, the ACLU lawsuit names Martin Vargas Arellano, Jose Ibarra Bucio and Teka Gulema, each of whom died soon after release.

Vargas Arellano contracted COVID-19 at the Adelanto ICE Processing Facility in San Bernardino County and had a stroke. The 55-year-old from Mexico was released from custody last year while brain-dead at a local hospital. He had repeatedly asked to be released from detention because of health conditions including diabetes, hypertension and hepatitis C.

Young women don’t have to die of sepsis, for God’s sake. Was this death preventable by early screening and early care? The answer would be yes.

— Coleen Kivlahan, medical director of the human rights asylum clinic at UC San Francisco

Ibarra Bucio, a 27-year-old from Mexico who was also detained at Adelanto, had a brain hemorrhage in 2019 and was transferred to a hospital while comatose. He died four weeks after being released from ICE custody when his family took him off life support.

Gulema, a 33-year-old Ethiopian man, became paralyzed from a bacterial infection while detained at a facility in Alabama and was transferred to a hospital where he remained for nearly a year. He was released from custody weeks before he died in 2016 at the hospital.

José Ibarra Bucio, 27, had been detained at the Adelanto ICE Processing Center for about a week when he called his wife in early February, saying he was desperate to get out.

“How many more individuals are out there that we don’t know about?” Cho said.

There are more. Guatemalan toddler Mariee Juárez, who acquired a viral lung infection while detained in Texas in 2018 and died at a hospital weeks after being released. Oscar López Acosta, who was infected with COVID-19 in an Ohio facility in 2020 and was released as his health deteriorated and died two weeks later. And Saliou Ndiaye from Senegal, who attempted suicide at Adelanto in 2017 and was released from custody while on life support.

Hoping to ensure the government’s continued responsibility for Ndiaye’s care, his lawyer Carrye Washington asked an immigration judge to find that ICE could not release an unconscious person and order him back into custody. Washington said the judge declined to intervene, and Ndiaye remains on life support.

Ten days passed after Vargas Arellano died before his lawyer learned about it by filing a missing-person’s report and calling the coroner’s office.

A court-appointed investigation into his death led to a scathing special master’s report last July on the actions of ICE, Adelanto and its contract healthcare provider, Wellpath. The report notes that the decision to release Vargas Arellano while comatose and near death resulted in his being “moved off the ‘books’ at ICE.”

“Because ICE released him to the hospital, all three were relieved of their obligations to report his death,” the report states. “Further, this seems to have been the sole purpose of the release.”

ICE declined to comment on Arellano’s case and others reviewed by The Times.

Dr. Marc Stern, a physician specializing in correctional healthcare who has served as an expert for the DHS Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, said that it may be more fiscally responsible to release someone from custody who is hospitalized. That way, he said, the government avoids spending taxpayer money on guards and paying medical bills that some hospitals already cover for low-income patients.

But Stern said that flouting reporting requirements indicates there could also be a political motivation in ICE’s release of sick detainees. All deaths should be reported, he noted, particularly when someone’s health deteriorates under ICE’s watch.

“Our system is fundamentally flawed in not defining deaths completely enough,” Stern said.

Rafe Foreman, a Texas attorney who represented Medina Leon’s family in their wrongful-death lawsuit, said he believes ICE has an incentive to release people who are about to die.

The case named as defendants MTC and its employees — the Otero facility warden and four healthcare providers. ICE and the Department of Homeland Security were not parties to the lawsuit, which was dismissed in court. Foreman said the case was resolved but declined to say whether there was an out-of-court settlement. Medina Leon’s parents declined to comment.

“This was the worst case of medical malpractice that I’ve seen in a while,” Foreman said. “From the minute she walked in there until she died, she was neglected.”

In court filings, lawyers for MTC denied the allegations, argued that Medina Leon’s family had no basis to receive punitive damages and said the case should be dismissed.

The lawyers also spelled out what happened after she died: No medical personnel were disciplined, and “no changes in policy, practice, protocols or procedures occurred.”

Times staff writer Paloma Esquivel in Los Angeles and Nelson Rauda Zablah in El Salvador contributed to this report.

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.