Warsaw Ghetto uprising’s 80th anniversary marked by Holocaust survivors, political leaders

- Share via

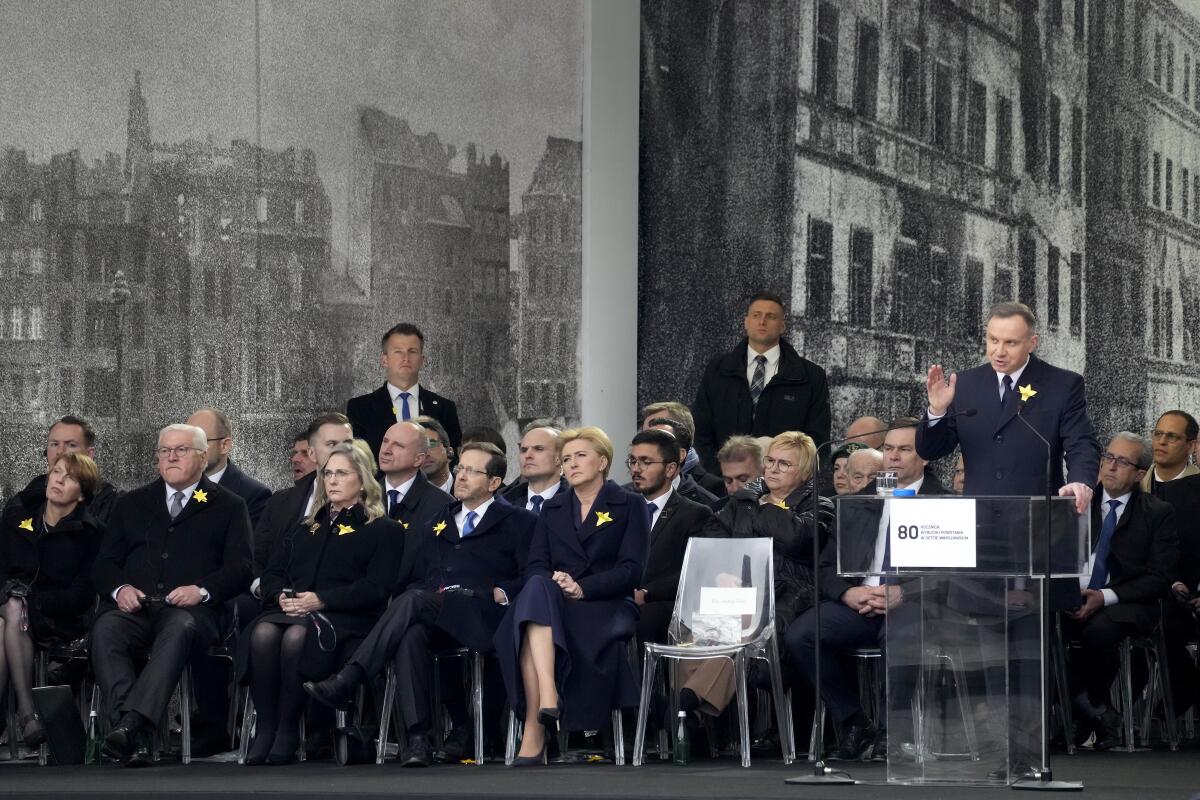

WARSAW — Presidents joined Holocaust survivors and their descendants to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising on Wednesday with a poignant sense that the responsibility for carrying on the memory of the Holocaust is passing from the witnesses to younger generations.

German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier said the lessons of his country’s aggression during Nazi rule hold a lesson as Russia’s attack on Ukraine has “destroyed the foundations of our European security order.”

“You in Poland, you in Israel, you know from your history that freedom and independence must be fought for and defended. You know how important it is for a democracy to defend itself,” Steinmeier said at a ceremony alongside Polish President Andrzej Duda and Israeli President Isaac Herzog.

“But we Germans have also learned the lessons of our history. ‘Never again’ means that there must be no criminal war of aggression like Russia’s against Ukraine in Europe.”

The anniversary honors the hundreds of young Jews who took up arms in Warsaw in 1943 against the overwhelming might of the Nazi army.

There are no fighters still alive. Marek Edelman, the last surviving commander, died in 2009. He remained in Poland and helped keep alive the memory of the revolt in his homeland. Simcha Rotem, a fighter who smuggled others out of the burning ghetto through sewage tunnels, died in 2018 in Israel, where he had settled.

New photographs — some never seen before — that were taken secretly during the Warsaw Ghetto uprising of 1943 are discovered in a family collection.

The small number of elderly surviving witnesses today were mostly children at the time of the revolt.

The commemorations, led by three presidents whose nations were forever shaped by World War II, took place in front of the Memorial to the Ghetto Heroes, on the spot where the fighting erupted.

Israel was founded after the war to give Jews a home where they could finally be safe after centuries of persecution in Europe.

Germany, which inflicted death and destruction across the vast areas that it occupied, has acknowledged its crimes and expressed remorse.

Simcha Rotem, an Israeli Holocaust survivor who was among the last known Jewish fighters from the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto uprising against the Nazis, has died.

Steinmeier once again begged forgiveness.

“As German federal president, I stand before you today and bow to the courageous fighters in the Warsaw Ghetto,” Steinmeier said. “I bow to the dead in deep sorrow.”

And Poland, where Europe’s largest prewar Jewish population lived and which was invaded and subjected to mass death and destruction, carries out its responsibility of preserving sites like the ghetto and the Auschwitz death camp, while also honoring the massive losses inflicted on the entire nation. Some 6 million Polish citizens were killed during the war, about 3 million of them Jews and the others mostly Christian Poles.

“Dear President Duda, dear President Herzog, many people in your two countries, in Poland and in Israel, have granted us Germans reconciliation despite these crimes,” Steinmeier said, calling that a “miracle of reconciliation” to be preserved into the future.

An exhibition brings back to Germany a diverse set of everyday objects that Jews took with them when they fled the Nazis.

Some of those participating in Wednesday’s observances traveled from as far as Australia and the United States to honor those who perished and also the rich Jewish civilization that is their heritage. Many hold their own private ceremonies, paying tribute to those departed at the Jewish cemetery or at various memorials on the former grounds of the ghetto.

Avi Valevski, a professor of psychiatry from Israel whose father, Ryszard Walewski, a doctor who led a group of some 150 warriors in the revolt, visited Warsaw with his wife, describing it as “more than an emotional moment.”

Valevski, 72, is working to preserve a history that his father rarely spoke to him about but that also carries an emotional burden. He was young when his father became ill and died in 1971, but today he pores through the documentation his father left behind and is trying to get one of his stories translated into English and published.

“He was quite proud of his fight against the Nazi beast — his words — but I suppose that the feeling of apprehension entered my soul until now,” Valevski said.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The Germans invaded Poland in 1939 and the following year set up the ghetto, the largest of many in occupied Poland.

It initially held some 380,000 Jews who were cramped into tight living spaces, and at its peak housed about a half-million people. Disease and starvation were rampant, and bodies often appeared on the streets.

The Jewish resistance movement in the Warsaw Ghetto grew after 265,000 men, women and children were rounded up in the summer of 1942 and killed at the Treblinka death camp. As word of the Nazi genocide spread, those who remained behind no longer believed German promises that they would be sent to labor camps.

A small group of rebels began to spread calls for resistance, carrying out isolated acts of sabotage and attacks. Some Jews began defying German orders to report for deportation.

Antisemitic hate crimes rose in New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, the U.S. cities with the largest Jewish populations, according to police data.

The uprising began when the Nazis entered the ghetto April 19, 1943, the eve of the Passover holiday. Three days later, the Nazis set the ghetto ablaze, turning it into a fiery death trap, but the Jewish fighters kept up their struggle for nearly a month before they were brutally vanquished. That was longer than some countries held out.

“I’m a New Yorker, but there is something that keeps drawing me back here,” said Barbara Jolson Blumenthal, whose parents survived the Warsaw Ghetto after a Pole helped them to escape and hide on the “Aryan” side of the city.

“And although such horrible things happened here, I remember my parents saying that they loved it here, that it was so wonderful here, and I walk the streets and I wonder if this is where my family was and where they walked,” Blumenthal said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.