A lifetime of racism makes Alzheimer’s more prevalent in Black Americans

- Share via

FREDERICKSBURG, Va. — Constance Guthrie is not yet dead, but her daughter has begun to plan her funeral.

It will be, Jessica Guthrie says, in a Black-owned funeral home, with the songs of their ancestors. She envisions a celebration of her mother’s life, not a tragic recitation of her long decline.

As it should be. Her mother has lived 74 years, many of them good, as a Black woman, a mother, educator and businesswoman.

But she is dying of Alzheimer’s disease, a scourge of Black Americans that threatens to grow far worse in the coming decades.

Black people are more likely to develop Alzheimer’s than white people in the United States. They are less likely to be correctly diagnosed, and their families often struggle to get treatment from a medical system filled with bias against them.

About 14% of Black people in America over the age of 65 have Alzheimer’s, compared with 10% of white people, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The disparity is likely even greater, because many Black patients aren’t correctly diagnosed.

And by 2060, cases are expected to increase fourfold among Black Americans.

While some risk factors may differ by race, the large disparities among racial groups can’t be explained just by genetics.

The problems start much earlier in life. Health conditions like heart disease and diabetes are known risk factors. Both are more common among Black populations, who are more likely to live near polluting industries and to have less access to healthy food, among other factors. Depression, high blood pressure, obesity and chronic stress can also raise the likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s. So can poverty.

The higher mortality rate among Black Americans resulted in 1.63 million excess deaths relative to white Americans over more than two decades, a study finds.

And overall, Black people don’t receive the same quality of healthcare throughout life as white people.

They often don’t get high-quality treatment — or any treatment — for the conditions that are risk factors. When they develop Alzheimer’s or other dementia-related disorders, they’re less likely to get medication to ease the symptoms.

And there’s the insidious impact of living with racism.

The trauma caused by racism can lead to increased stress, which can in turn cause health problems like inflammation, which is a risk factor for cognitive decline, said Carl V. Hill, chief diversity, equity and inclusion officer of the Alzheimer’s Assn.

“Because of this structural racism that creates poor access to health, medication, housing, those who experience racism and discrimination are not provided a pathway to lower their risk,” Hill said.

It is, he said, “a one-two punch.”

For Jessica Guthrie, it has meant that the final years of her mother’s life have been filled not with peace, but heartache and frustration, as she navigates doctors who don’t believe her when she says her mom is suffering. In the slow, plodding walk that is her mother’s final years, she has few healthcare partners.

A new California Health Care Foundation survey found Black and Latino Californians were more likely to have negative health provider experiences and medical debt.

“It has been pervasive across multiple doctors, emergency rooms and hospital doctors,” Guthrie said. “Not being listened to, not believed, not given the full treatment.”

“To be a caregiver of someone living with Alzheimer’s is that you watch your loved one die every day,” she said. “I’ve been grieving my mom for seven years.”

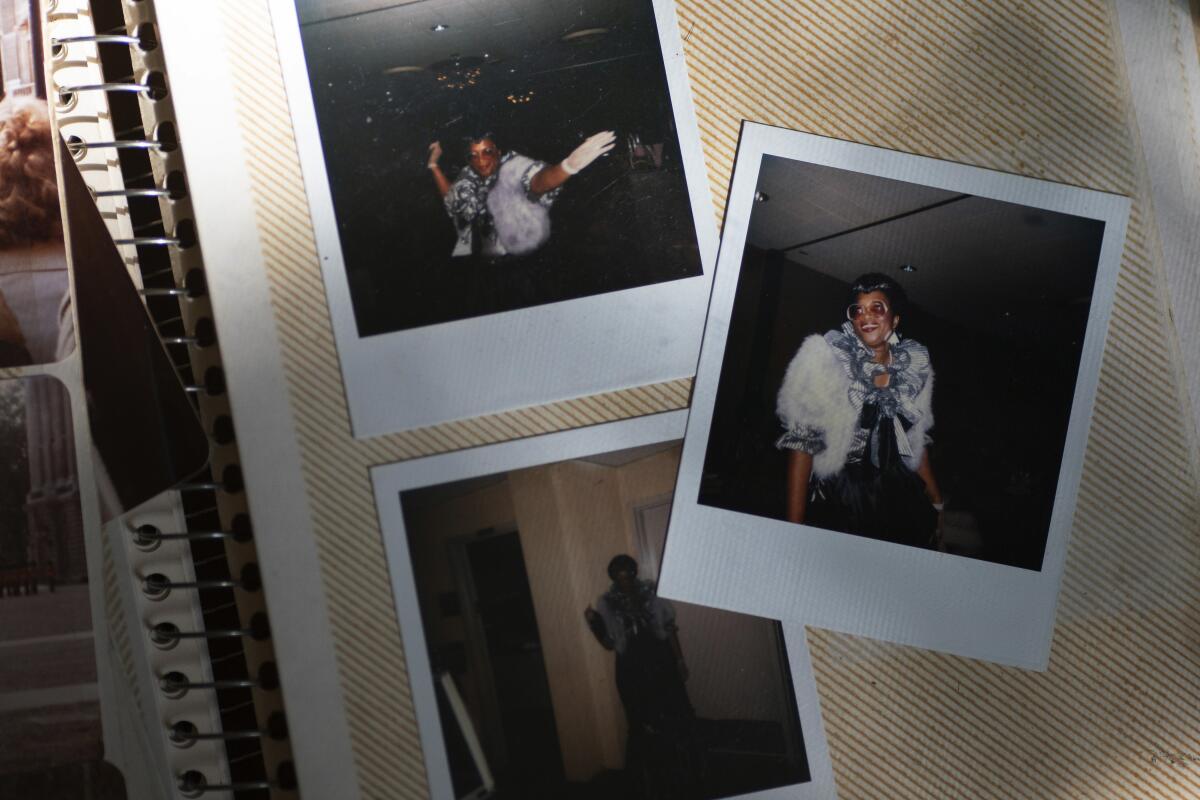

The salon was called Hair by Connie, and for 18 years it was the place to go in Alexandria, Va., for many Black women who wanted to look their best. Reigning over the shop was its owner, Constance Guthrie.

She traveled the world, attending hair shows. She opened her salon to fashion shows like the “Tall, Full and Sassy” event advertised in an old flier she now keeps in a box of mementos. She donned dazzling, colorful and flamboyant outfits to match her larger-than-life personality.

In the 1990s, she made the difficult decision to close her beloved salon and move. She bought a home in Fredericksburg so her daughter could attend the best schools, and later became a paraprofessional in the local school district, giving her a schedule that meant she never had to miss oratorical contests or choir recitals.

She was always there for her only child. They often stayed up into the wee hours of the night working on school projects together. Despite their meager means, her daughter grew up surrounded by encouragement and love.

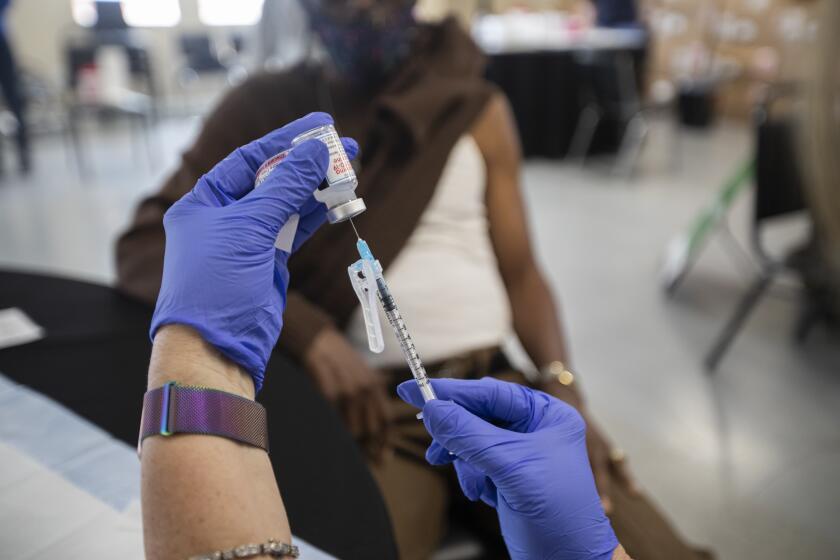

U.S. health officials have approved a new Alzheimer’s drug that modestly slows the brain-robbing disease

“My mother gave up everything to make sure that I had the greatest support, the greatest opportunities,” Jessica Guthrie recalled. “We were like two peas in a pod.”

Her mother’s hard work paid off. Guthrie became a teacher and later moved to Dallas to chase her dreams and build her own life, becoming a successful chief program officer for an education service.

Then, seven years ago, her mother began her descent into dementia.

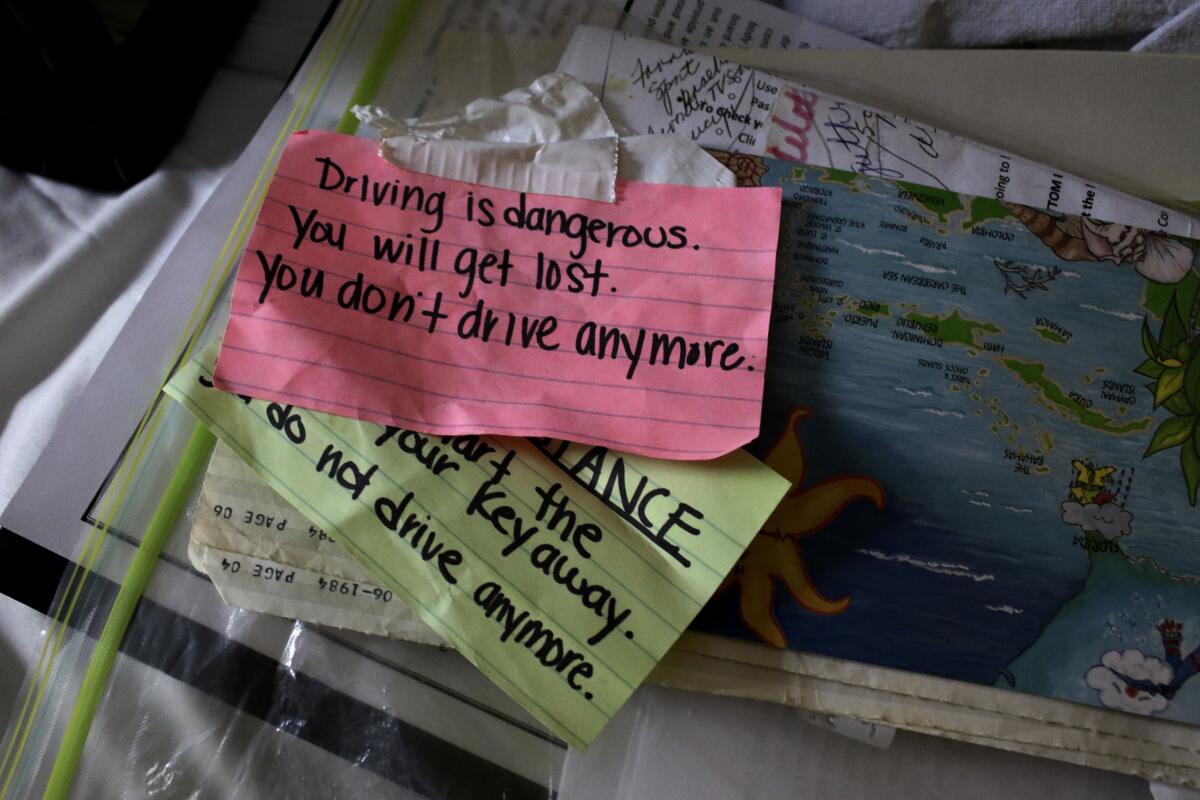

She started to forget simple things, like where her keys were. She lost her way coming home from work on a route she had traveled almost daily for 18 years. She got into a car accident.

The troubling incidents became more frequent, worrying her daughter, who was still hundreds of miles away in Texas.

They tried to use sticky notes to remind her of her limitations and daily tasks. Some of the colorful notes still line the walls of the family’s home.

For a woman who had grown accustomed to being so independent, it was hard for her mother to accept that she needed help.

“She spent so long trying to hide it,” Guthrie said. “Like, ‘Oh, I’m good, I’m fine. I just forgot.’ But you could tell that a lot of her anxiety and stress was because she was trying to cover this up from other people.”

Her mother began to wander around her neighborhood. Guthrie and nearby loved ones tried bolting the door to prevent her from wandering.

Then a neurologist confirmed that she was suffering early cognitive decline and that it was likely Alzheimer’s.

Constance Guthrie was just 66 when she was diagnosed.

It’s not just the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study, Black Americans’ skepticism about COVID vaccines is fueled by health inequities they face now.

Soon after, Jessica Guthrie made the tough decision to pack up and leave Dallas to care for her mother full time. She recently began working remotely again after taking an extended leave of absence to care for her.

Her mother had never had the common risk factors of diabetes or high blood pressure. She was fairly active and healthy, and would often walk around her neighborhood. But in 2015, she suffered a transient ischemic attack, or a “mini-stroke,” which is a brief disruption in the blood supply to part of the brain.

Guthrie believes the mini-stroke could have been caused in part by the heavy stress her mother endured at her job, where she worked for 18 years as a special education paraprofessional.

Guthrie wonders whether genetics may have also played a role: Her mother’s aunts are all living with the disease. Her mother’s brother, who was a doctor, has started to experience cognitive decline.

Lost in her own mind, Constance Guthrie can no longer testify to the difficulties she has endured — as a mother and as a Black entrepreneur running a business on her own.

But Jessica Guthrie can attest to her own struggles as a Black caregiver, trying to ensure that her mother receives appropriate care.

In 2018, her mother started pointing at her stomach, repeatedly, indicating she was in pain. Her daughter took her to her primary care physician, who is white and brushed the concerns aside.

“My mother couldn’t articulate that there was significant pain in the moment, and the doctor of the practice basically said, ‘Oh, well, you know, sometimes they just come in and put on a show, and it seems like she’s fine,’” Guthrie said. “They asked, ‘Are you sure she’s in so much pain?’”

They sent her mother home without performing further tests. But the pain persisted.

The next day, Guthrie took her to the emergency room, where a Black doctor ordered the necessary imaging. Her mother needed emergency surgery to correct a painful, protruding hernia.

Then there was the time she took her mother to the ER for intense leg pain. She had arthritis in her knee, but Guthrie suspected something more serious.

The doctor said her mother likely just needed rehab for her bad knee. Guthrie advocated for more testing, which showed that her mother had a blood clot in her leg.

“Racism is implicit and deeply rooted in the air that we breathe,” said Guthrie, who has started an Instagram account to chronicle her experiences caring for her mother.

The problems Black people face getting medical care are pervasive. Those living with serious illnesses get less help managing pain and other symptoms, and their communication with doctors is worse, according to the Center to Advance Palliative Care.

Studies show they are less likely to receive dementia-related medication that can help ease symptoms like the hallucinations and depression that make the disease particularly terrifying for families.

Among nonwhite caregivers, half or more say they have faced discrimination when navigating healthcare settings for those in their care. Their top concern is that providers or staff do not listen to them due to their race.

And there are barriers to even being diagnosed properly. A recent study found that Black participants in Alzheimer’s disease studies were 35% less likely to be diagnosed than white participants.

Part of the problem is a shortage of Black doctors. Just 1 in 3 physicians in the United States is Black, Indigenous, Latino or Asian. That lack of representation has had a compounding effect on the care that Black people receive — especially later in life, when older Americans suffering from illnesses like Alzheimer’s become unable to advocate for themselves.

All of these factors put an added burden on Black families providing care.

Through Instagram, Guthrie regularly hears from other Black caregivers, mostly women, who have similar stories of not being heard, feeling isolated or being denied proper treatment.

“I think that part of my journey would have looked significantly different if I were a middle-aged white person or a white male,” she said. “I would have been listened to the first time.”

Jessica Guthrie has spent the last several months preparing for her mother’s death, making sure every detail is perfect.

But in an unexpected twist, she learned in February that her mother would be discharged from home hospice care in early March. Medicare typically covers hospice care for those who are terminally ill, with a life expectancy of six months or less.

Although her mother is in the last stage of Alzheimer’s disease, she has been deemed stable.

Both her appetite and water intake are great. Her skin is glowing. She still shows glimmers of her sassy spirit.

On the surface, this is good news. Guthrie is relishing every extra day she has with her mother.

Still, the discharge feels like a slap in the face.

Several studies have found that Black patients with various serious illnesses are less likely to be referred to hospice care or to use it.

Losing hospice services means losing equipment and supplies, including the hospital-grade bed that Guthrie’s mother sleeps in, the lift to get her out of bed, and her wheelchair. Gone are the weekly nurse visits, vital checks, the social worker and the extra services that her mother loved — music and massage therapy.

Guthrie is concerned about how she’ll handle the next medical emergency. She’ll have to rely on local hospitals that had provided her mother with problematic care.

“Everything’s gone, and it feels like I’m back at square one again,” she said. “I feel like the system’s failed us, and has failed so many other caregivers.”

It’s the latest burden, but maybe not the last, and it’s taking its toll.

Guthrie is 34, and many of her friends are now married, starting families, traveling and investing money for the future.

But she’s had to spend money on her mother’s care and largely put her life on hold.

“When you think about how I spent so long trying not to repeat this cycle of poverty, now I’m sitting in a place where I make a pretty good salary, and yet I’m not setting myself up for the future that I know that I should have,” she said.

Some days she mourns the life she might have had and everything she has sacrificed to help her mother. She sees undeniable parallels with all that her mother sacrificed for her. But she wouldn’t change a thing.

Her exhausting experience as a caregiver has added purpose to her life. She feels she is also helping other Black caregivers to be seen and heard.

For now, she is happy to spend time with the woman she calls “CG.”

Every morning after her mother wakes up in her small room, Guthrie flips on the TV to the gospel music station. “Music brightens my mom. She would sing no matter if she was on key or not.”

She also sings to her mother as she’s changing or feeding her. On a recent day she tried making it through “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” as she massaged her mother’s fingers, but her voice cracked and she began crying.

“You saying goodbye?” her mother mumbled.

Constance Guthrie doesn’t sing or clap along anymore, but she lightly tapped her feet under her blanket. And she let out a low, steady hum.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.