The story behind Juneteenth and how it became a federal holiday

- Share via

Americans on Monday will celebrate Juneteenth, marking the day the last enslaved people in the country learned they were free.

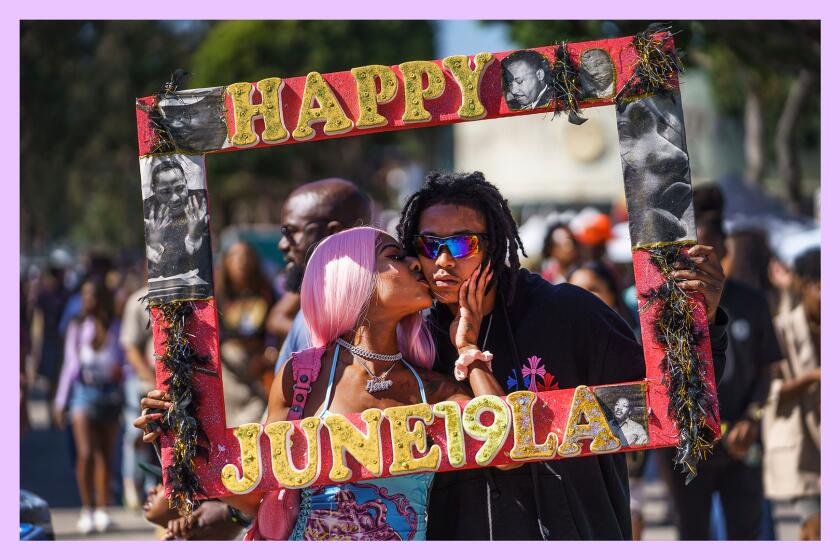

For generations, Black Americans have recognized the end of one of the darkest chapters in U.S. history with joy, in the form of parades, street festivals, performances and cookouts.

The U.S. government was slow to embrace the occasion — it was only in 2021 that President Biden signed a bill passed by Congress to set aside Juneteenth, or June 19th, as a federal holiday.

Just as many people are learning what Juneteenth is all about, the holiday’s traditions are facing new pressures, including political rhetoric condemning efforts to teach Americans about the nation’s racial history, companies using the holiday as a marketing event and people partying without understanding why.

Here is a look at the origins of Juneteenth and how it became a federal holiday.

Juneteenth traces itself to the day in 1865 — more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation — that brought news of freedom to enslaved people in Galveston, Texas. Now a federal holiday, it’s become more popular than ever.

How did Juneteenth start?

The celebrations began with enslaved people in Galveston, Texas.

Although President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation freed enslaved people in 1863, it could not be enforced in many places in the South until the Civil War ended in 1865. Even then, some white people who had profited from their forced, unpaid labor were reluctant to share the news.

In a 1941 interview, Laura Smalley, who was freed from a plantation near Bellville, Texas, recalled that the man she referred to as “old master” came home from fighting in the Civil War and didn’t tell the people he had enslaved what had happened.

“Old master didn’t tell, you know, they was free,” Smalley said. “I think now they say they worked them, six months after that. Six months. And turn them loose on the 19th of June. That’s why, you know, we celebrate that day.”

News that the war had ended and those who had been enslaved were free finally reached Galveston when Union Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger and his troops arrived in the Gulf Coast city on June 19, 1865, more than two months after Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant.

Granger delivered General Order No. 3, which said: “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.”

Slavery was permanently abolished six months later, when Georgia ratified the 13th Amendment.

The next year, the free people of Galveston celebrated Juneteenth, an observance that has continued and has spread around the world. Events around the holiday include concerts, parades and readings of the Emancipation Proclamation.

What does ‘Juneteenth’ mean?

It’s a portmanteau blending the words “June” and “nineteenth.”

The holiday has also been called Juneteenth Independence Day, Freedom Day, second Independence Day and Emancipation Day.

It began with church picnics and speeches and spread as Black Texans moved elsewhere.

Most U.S. states now hold celebrations honoring Juneteenth as a holiday or a day of recognition, like Flag Day. Juneteenth is a paid holiday for state employees in Texas, New York, Virginia, Washington and Nevada. Hundreds of companies give workers the day off.

Opal Lee, a former teacher and activist, is credited with rallying others behind a campaign to make Juneteenth a federal holiday. The 96-year-old had vivid memories of celebrating Juneteenth as a child in East Texas with music, food and games.

In 2016, the “little old lady in tennis shoes” walked through her home city of Fort Worth, then in other cities before arriving in Washington, D.C. Soon, celebrities and politicians were lending their support.

Lee was one of the people standing next to Biden when he signed Juneteenth into law.

How have Juneteenth celebrations evolved?

The national reckoning over race ignited by the 2020 murder of George Floyd by police helped set the stage for Juneteenth to become the first new federal holiday since 1983, when Martin Luther King Jr. Day was created.

The Juneteenth bill was sponsored by Sen. Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.) and had 60 co-sponsors — a show of bipartisan support as lawmakers struggled to overcome divisions that

are still simmering three years later.

The two votes taken by the L.A. City Council on Friday deal with the minutiae of holiday rules for an employer with tens of thousands of employees.

Now there is a movement to position the holiday as an opportunity for activism and education, with community service projects aimed at addressing racial disparities and educational panels on topics such as healthcare inequity and the need for parks and green spaces in urban areas.

Like most holidays, Juneteenth has seen its fair share of commercialism. Retailers, museums and other venues have capitalized on it by selling themed T-shirts, party ware and food products. Some of the marketing has misfired, provoking a social media backlash.

Supporters of the holiday have worked to make sure Juneteenth celebrators don’t forget why the day exists.

“In 1776 the country was freed from the British, but the people were not all free,” Dee Evans, national director of communications of the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation, said in 2019. “June 19, 1865, was actually when the people and the entire country was actually free.”

There’s a push to use the day to remember the sacrifices that were made for freedom in the United States — especially in these racially and politically charged times.

“Our freedoms are fragile, and it doesn’t take much for things to go backward,” said Para LaNell Agboga, museum site coordinator at the George Washington Carver Museum, Cultural and Genealogy Center in Austin, Texas.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.