Inside the meeting of GOP electors who sought to thwart Biden’s election win in Georgia

- Share via

ATLANTA — It was a bad place to keep a secret.

When Republicans gathered on Dec. 14, 2020, claiming to be legitimate electors casting the state’s 16 electoral votes for Donald Trump, they met at the Georgia Capitol in a room just upstairs from the building’s public entrance. A Trump campaign official asked for the electors’ “complete discretion,” telling them to say only that they were meeting with two state senators who were there.

“Your duties are imperative to ensure the end result — a win in Georgia for President Trump — but will be hampered unless we have complete secrecy and discretion,” Robert Sinners wrote in an email uncovered by investigators.

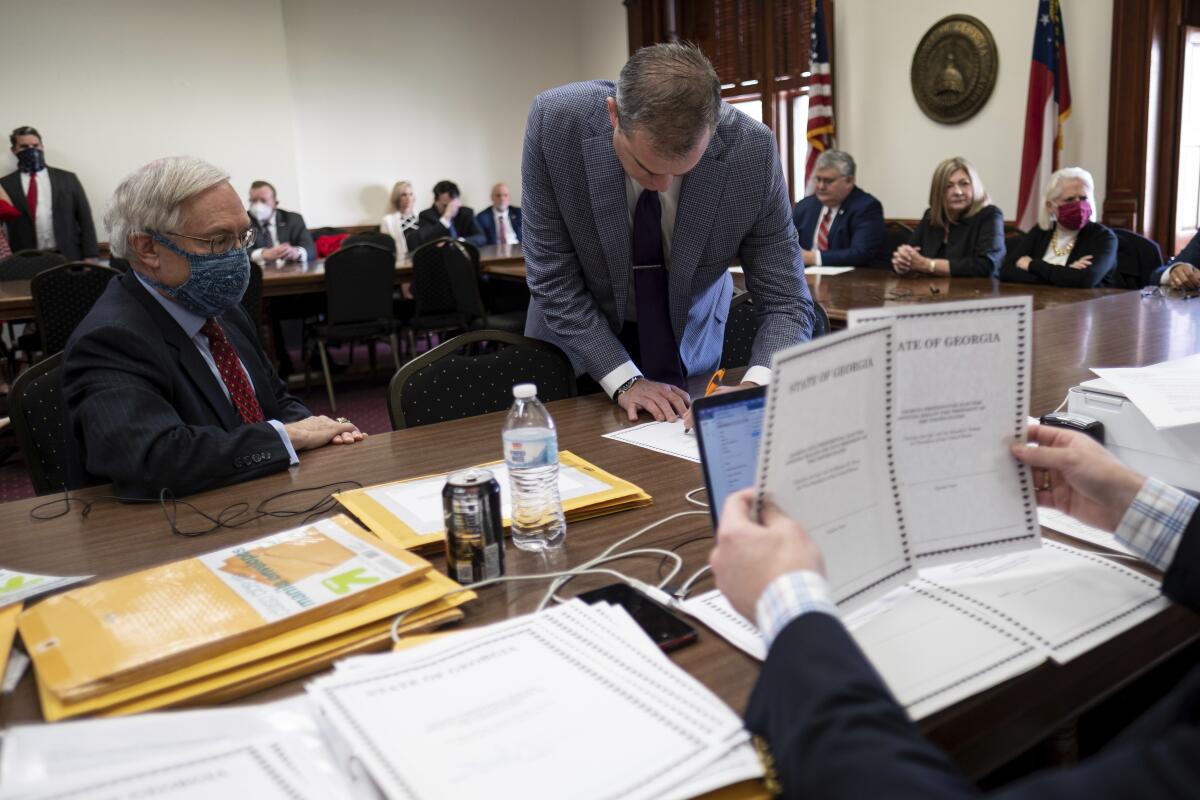

But reporters for the Associated Press and other news organizations noticed the Republicans entering the building and were eventually allowed to enter the room, where they photographed and recorded video of the proceeding.

In the chaotic weeks after the 2020 election, the gathering’s significance wasn’t immediately clear. But it has emerged as a crucial element in the prosecution of Trump and 18 others who were indicted by a Georgia grand jury in August on allegations of trying to overturn Democrat Joe Biden’s narrow win in the state.

Despite their sometimes moderate records, vulnerable California Republicans kept backing Jim Jordan, Donald Trump’s ultraconservative and ultimately failed pick for speaker.

The meeting was cited as a central element in court proceedings Friday as part of a last-minute deal with lawyer and defendant Kenneth Chesebro, who pleaded guilty to one felony charge of conspiracy to file false documents.

Chesebro, who prosecutors have said helped originate the plan for Republican electors to meet in swing states where Biden was certified as the winner, is now one of three people who have pleaded guilty in the case.

Attorney Sidney Powell pleaded guilty Thursday to six misdemeanors for intentional interference in the performance of election duties as part of a broader conspiracy prosecutors say violated Georgia’s anti-racketeering law.

While Democrats met in Georgia’s ornate state Senate chamber to cast electoral votes for Biden in 2020, the Republicans sat at three worn and nicked conference tables to consider options for keeping Trump in the White House. According to the case laid out by prosecutors, these were “fake,” “false” or “fraudulent” electors. At least eight Georgia Republican electors present that day have since agreed to testify in exchange for immunity from state charges.

The meeting was led by David Shafer, then chairman of the Georgia Republican Party. Lending the gathering the air of an official proceeding was the presence of a court reporter — something Shafer denied to Fulton County, Ga., prosecutors in April 2022. That denial contributed to a charge of false statements and writings against Shafer.

Additional improvised elements of the meeting became clear as the group considered its officers. Shawn Still, now a state senator, wasn’t initially elected as secretary, for instance. But halfway through the meeting, Shafer noted that Still was listed on documents as secretary.

“I would like to avoid reprinting the documents,” Shafer said, asking the electors to replace another Republican with Still.

One of three people the grand jury indicted for participating in the vote, Still may have been dragged into legal jeopardy when he was elected secretary.

The third indicted elector, Cathy Latham, was also charged with helping outsiders access state voting equipment in southern Georgia’s Coffee County.

As the meeting unfolded, the Republicans sought to replace four electors who had previously lined up to support Trump. One had registered to vote in Alabama and was no longer

eligible. State Sen. Burt Jones, later elected lieutenant governor with Trump’s backing, took his spot.

Three other GOP electors didn’t show up, including John Isakson Jr., son of late Republican U.S. Sen. Johnny Isakson. In 2022, the younger Isakson told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that he’d stayed away because the meeting seemed like “political gamesmanship.”

Prosecutors allege Shafer and Still committed yet more felonies by creating a document claiming to fill those vacancies. State law says that action needed Gov. Brian Kemp’s consent. The Republican governor had days earlier certified Biden as Georgia’s winner for a

second time after a recount.

Sinners, the Trump campaign official who helped arrange the meeting, printed new elector certificates on a noisy portable printer. The racket of the machine — in an unadorned space usually set aside for state lawmakers to host constituents — added to the meeting’s mundane and bureaucratic feel.

One by one, the 16 Republicans were called. Each walked to the table and signed certificates pronouncing Trump and then-Vice President Mike Pence as the preferred choice of Georgia voters.

That was the moment, grand jurors allege, when they committed the felonies for which they have been charged: impersonating a public officer, first-degree forgery and making false statements in writing.

“They were fake electors; they were impersonating electors. They were no electors,” Fulton County prosecutor Anna Cross told a federal judge in September, adding there was no evidence that Shafer, Still, Latham or the other Republicans believed Trump had actually won.

The group’s defenders have called them “alternate” or “contingent” electors who were just trying to keep Trump’s legal options open as a lawsuit challenged Georgia’s election results. Some Republicans argue that Trump never got a fair shake in Georgia because that lawsuit was never tried, despite a state law calling for election challenges to be heard within 20 days.

A state Republican Party website raising money to defend the supposed electors calls them “patriots who served.”

“If we did not hold this meeting, then our election contest would effectively be abandoned,” Shafer said at the December meeting to lawyer Ray Smith, who was there advising the electors and has also been indicted. “And so the only way for us to have any judge consider the merits of our complaint, the thousands of people who we allege voted unlawfully, is for us to have this meeting.”

Shafer has defended his actions by citing the1960 presidential election in Hawaii, where Democrats met after Republican Richard Nixon was certified as the state’s winner. The Democrats sent three electoral votes for John F. Kennedy to the U.S. Senate.

Todd Zywicki, a law professor at George Mason University in Virginia, has said in a signed declaration that actions by Shafer and other Republican electors in Georgia were “lawful, reasonable, proper and necessary” considering the election contest and the Hawaii precedent.

The defendants’ lawyers argue it was up to Congress to determine which slates should be counted.

But Fulton County Dist. Atty. Fani Willis’ office, in a court filing, disputed Shafer’s claim that the actions of Georgia Republicans in 2020 bore any similarity to those of Hawaii Democrats in 1960. Her staff cites a major distinction: that Democrats eventually won a recount in Hawaii that a court affirmed and the governor certified, sending official documents to the Senate.

“The factual situations are so readily distinguishable as to make the comparison meaningless,” Willis’ team wrote, arguing against Shafer’s attempt to remove his case to federal court.

Willis’ office wrote that the Republicans’ meeting “was used to further a clumsy but relentless pressure campaign on the vice president and state legislatures, and as a means to publicly undermine the legitimate results of the presidential election.”

Sinners, the Trump campaign staffer, now rejects the purpose of the meeting. He denies the notion that Trump won Georgia and now works for Brad Raffensperger, Georgia’s Republican secretary of state, who came to national attention for rebuffing pressure from the then-president to “find” enough votes to reverse his loss.

Sinners cooperated with the U.S. House committee that investigated the violent insurrection on Jan. 6, 2021. He hasn’t said whether he’s cooperating with Willis.

In an interview, he made clear he regretted what unfolded in the Georgia Capitol during one of the most turbulent periods in American politics.

“This was an ill-advised attempt by the former president’s campaign to create a false reality — a victory,” Sinners said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.