Oregon’s first-in-the-nation drug decriminalization law faces growing resistance

- Share via

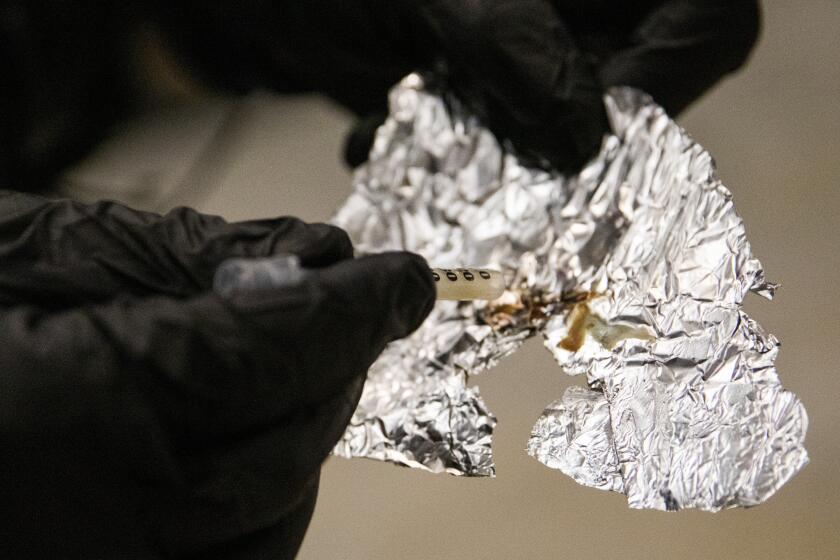

PORTLAND, Ore. — Oregon’s first-in-the-nation law that decriminalized the possession of small amounts of heroin, cocaine and other illicit drugs in favor of an emphasis on addiction treatment is facing strong headwinds in the progressive state after an explosion of public drug use fueled by the proliferation of fentanyl and a surge in deaths from opioids, including those of children.

“The inability for people to live their day-to-day life without encountering open-air drug use is so pressing on urban folks’ minds,” said John Horvick, vice president of polling firm DHM Research. “That has very much changed people’s perspective about what they think Measure 110 is.”

When the law was approved by 58% of Oregon voters three years ago, supporters championed Measure 110 as a revolutionary approach that would transform addiction by minimizing penalties for drug use and investing instead in recovery.

But even top Democratic lawmakers who backed the law, which will likely dominate the upcoming legislative session, say they’re now open to revisiting it after the biggest increase in synthetic opioid deaths among states that have reported their numbers.

The cycle of addiction and homelessness spurred by fentanyl is most visible in Portland, where it’s not unusual to see people shooting up in broad daylight on busy city streets.

“Everything’s on the table,” said Democratic state Sen. Kate Lieber, co-chair of a new joint legislative committee created to tackle addiction. “We have got to do something to make sure that we have safer streets and that we’re saving lives.”

Since Oregon residents voted in 2020 to decriminalize hard drugs and dedicate millions of dollars to treatment, few people have requested the services.

Measure 110 directed the state’s cannabis tax revenue toward drug addiction treatment services while decriminalizing the possession of so-called “personal use” amounts of illicit drugs. Possession of less than a gram of heroin, for example, is subject only to a ticket and a maximum fine of $100.

Those caught with small amounts of drugs can have the citation dismissed by calling a 24-hour hot line to complete an addiction screening within 45 days, but those who don’t do a screening are not penalized for failing to pay the fine. In the first year after the law took effect in February 2021, only 1% of people who received citations for possession sought help via the hot line, state auditors found.

Critics of the law say this doesn’t create an incentive to seek treatment.

Republican lawmakers have urged Democratic Gov. Tina Kotek to call a special session to address the issue before the Legislature reconvenes in February. They have proposed harsher sanctions for possession and other drug-related offenses, such as mandatory treatment, and easing restrictions on placing people under the influence on holds in facilities such as hospitals if they pose a danger to themselves or others.

“Treatment should be a requirement, not a suggestion,” a group of Republican state representatives said in a letter to Kotek.

At least 193 homeless people died in Oregon’s Multnomah County in 2021, with drugs including meth and fentanyl contributing to about 60% of those deaths.

Law enforcement officials who have testified before the new legislative committee on addiction have proposed reestablishing drug possession as a class A misdemeanor, which is punishable by up to a year in jail or a $6,250 fine.

“We don’t believe a return to incarceration is the answer, but restoring a [Class A] misdemeanor for possession with diversion opportunities is critically important,” Jason Edmiston, chief of police in the small, rural city of Hermiston in northeast Oregon, told the committee.

However, data shows decades of criminalizing possession hasn’t deterred people from using drugs. In 2022, nearly 25 million Americans, roughly 8% of the population, reported using illicit drugs other than marijuana in the previous year, according to the annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Some lawmakers have suggested focusing on criminalizing public drug use rather than possession. Alex Kreit, assistant professor of law at Northern Kentucky University and director of its Center on Addiction Law and Policy, said such an approach could help curb visible drug use on city streets but wouldn’t address what’s largely seen as the root cause: homelessness.

“There are states that don’t have decriminalization that have these same difficult problems with public health and public order and just quality-of-life issues related to large-scale homeless populations in downtown areas,” he said, mentioning California as an example.

Backers of Oregon’s approach say decriminalization isn’t necessarily to blame, as many other states with stricter drug laws have also reported increases in fentanyl deaths.

The plan, which would include distribution of glass pipes for methamphetamine and crack users, is opposed by Portland’s mayor and other officials.

But estimates from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show, among the states reporting data, Oregon had the highest increase in synthetic opioid overdose fatalities when comparing 2019 with the 12-month period ending June 30, a thirteenfold surge from 84 deaths to more than 1,100.

Among the next highest was neighboring Washington state, which saw its estimated synthetic opioid overdose deaths increase sevenfold when comparing those same time periods, CDC data shows.

Nationally, overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids such as fentanyl roughly doubled over that time span. Roughly two-thirds of all deadly overdoses in the U.S. in the 12 months ending June 30 involved synthetic opioids, federal data shows.

Supporters of Oregon’s law say it was confronted by a perfect storm of broader forces, including the COVID-19 pandemic, a mental health workforce shortage and the fentanyl crisis, which didn’t reach fever pitch until after the law took effect in early 2021.

A group of Oregon lawmakers recently traveled to Portugal, which decriminalized the personal possession of drugs in 2001, to learn more about its policy. State Rep. Lily Morgan, the only Republican legislator on the trip, said Portugal’s approach was interesting but couldn’t necessarily be applied to Oregon.

“The biggest glaring difference is they’re still not dealing with fentanyl and meth,” she said, noting the country also has universal healthcare.

Portland, Ore., long a famously progressive city, faces a crisis of confidence as it grapples with homelessness and crime. Residents can’t agree on solutions.

Despite public perception, the law has made some progress by directing $265 million of cannabis tax revenue toward standing up the state’s new addiction treatment infrastructure.

The law also created what are known as Behavioral Health Resource Networks in every county, which provide care regardless of a patient’s ability to pay. The networks have ensured about 7,000 people entered treatment from January to March of this year, doubling from nearly 3,500 people from July through September 2022, state data shows.

The law’s funding also has been key for providers of mental health and addiction services because it has “created a sustainable, predictable funding home for services that never had that before,” said Heather Jefferis, executive director of the Oregon Council for Behavioral Health, which represents such providers.

Horvick, the pollster, said public support for expanding treatment remains high despite pushback against the law.

“It would be a mistake to overturn 110 right now because I think that would make us go backwards,” Lieber, the Democratic state senator, said. “Just repealing it will not solve our problem. Even if we didn’t have 110, we would still be having significant issues.”

AP writer Geoff Mulvihill in Philadelphia contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.