Voting ends in the last round of India’s election, a referendum on Modi’s decade in power

- Share via

NEW DELHI — India’s six-week-long national election came to an end Saturday with most exit polls projecting Prime Minister Narendra Modi is set to extend his decade in power with a third consecutive term.

During the grueling, multi-phase election, candidates crisscrossed the country, poll workers hiked to remote villages, and voters lined up for hours in sweltering heat. Now all that’s left is to wait for the results, which are expected to be announced Tuesday.

The election is considered one of the most consequential in India’s history. If Modi wins, he’ll be only the second Indian leader to retain power for a third term after Jawaharlal Nehru, the country’s first prime minister.

Exit polls by major television news channels projected Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party and its allies were leading over the broad opposition alliance led by the Congress party. Most exit polls projected BJP and its allies could win more than 350 seats out of 543 — far ahead of the 272 seats needed to form the next government.

Indian television channels have had a mixed record in the past in predicting election results.

Modi’s campaign began on a platform of economic progress, with vows to uplift the poor and turn India into a developed nation by 2047. But it turned increasingly shrill in recent weeks as Modi escalated polarizing rhetoric in incendiary speeches that targeted the country’s Muslim minority, who make up 14% of India’s 1.4 billion people.

After campaigning ended Thursday, Modi went to a memorial site honoring a famous Hindu saint to meditate on national television. The opposition Congress party called it a political stunt and said it violated election rules as the campaigning period has ended.

When the election kicked off in April, Modi and his BJP were widely expected to clinch another term.

Since coming to power in 2014, Modi has enjoyed immense popularity. His supporters see him as a self-made, strong leader who has improved India’s standing in the world, and credit his pro-business policies with making the economy the world’s fifth-largest.

At the same time, his rule has seen brazen attacks and hate speech against minorities, particularly Muslims. India’s democracy, his critics say, is faltering and Modi has increasingly blurred the line between religion and state.

But as the campaign ground on, his party faced stiff resistance from the opposition alliance and its main face, Rahul Gandhi of the Congress party. They have attacked Modi over his Hindu nationalist politics and are hoping to benefit from growing economic discontent.

Pre-poll surveys showed that voters were increasingly worried about unemployment, the rise in food prices and an overall sentiment that only a small portion of Indians have benefited despite brisk economic growth under Modi, making the contest appear closer than initially anticipated.

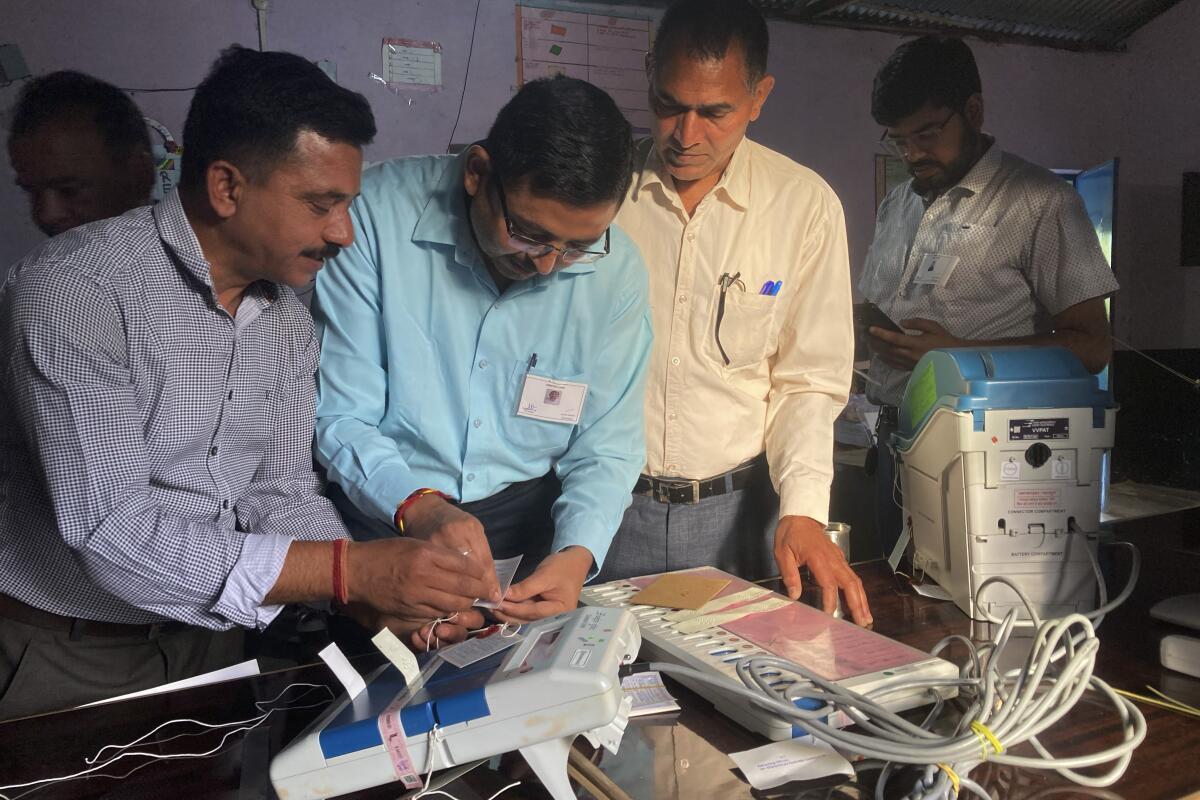

The seventh round of polls covered 57 constituencies across seven states and one union territory, completing a national election to fill all 543 seats in the powerful lower house of parliament. Nearly 970 million voters — more than 10% of the world’s population — were eligible to elect a new parliament for five years. More than 8,300 candidates ran for the office.

In Kolkata, the capital of West Bengal, voters lined up outside polling stations early Saturday morning to avoid the scorching heat. Modi was challenged there by the state’s chief minister, Mamata Banerjee, who heads the regional Trinamool Congress party.

“There is a crunch for jobs now in the present market. I will vote for the government that can uplift jobs. And I hope those who cannot get jobs, they will get jobs,” said Ankit Samaddar.

In this election, Modi’s BJP — which controls much of India’s Hindi-speaking northern and central parts — sought to expand their influence by making inroads into the country’s eastern and southern states, where regional parties hold greater sway.

The BJP also banked on consolidating votes among the Hindu majority, who make up 80% of the population, after Modi opened a long-demanded Hindu temple on the site of a razed mosque in January.

Modi ramped up anti-Muslim rhetoric after voter turnout dipped slightly below 2019 figures in the first few rounds of the 2024 polls, in a move seen as a bid to energize his core Hindu voter base. But analysts say it also reflected the absence of a single big-ticket campaign issue, which Modi has relied on to power previous campaigns.

In 2014, Modi’s status as a political outsider with plans to crack down on deep-rooted corruption won over voters disillusioned with decades of dynastic politics. And in 2019, he swept the polls on a wave of nationalism after his government launched airstrikes into rival Pakistan in response to a suicide bombing in Kashmir that killed 40 Indian soldiers.

But things are different this time, analysts say, giving Modi’s political challengers a potential opportunity.

“The opposition somehow managed to derail his plan by setting the narrative to local issues, like unemployment and the economy. This election, people are voting keeping various issues in mind,” said Rasheed Kidwai, a political analyst.

Saaliq and Pathi write for the Associated Press. AP video journalist Shonal Ganguly contributed from Kolkata, India.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.