Pakistanis question teachers, students at seminary attended by San Bernardino shooter

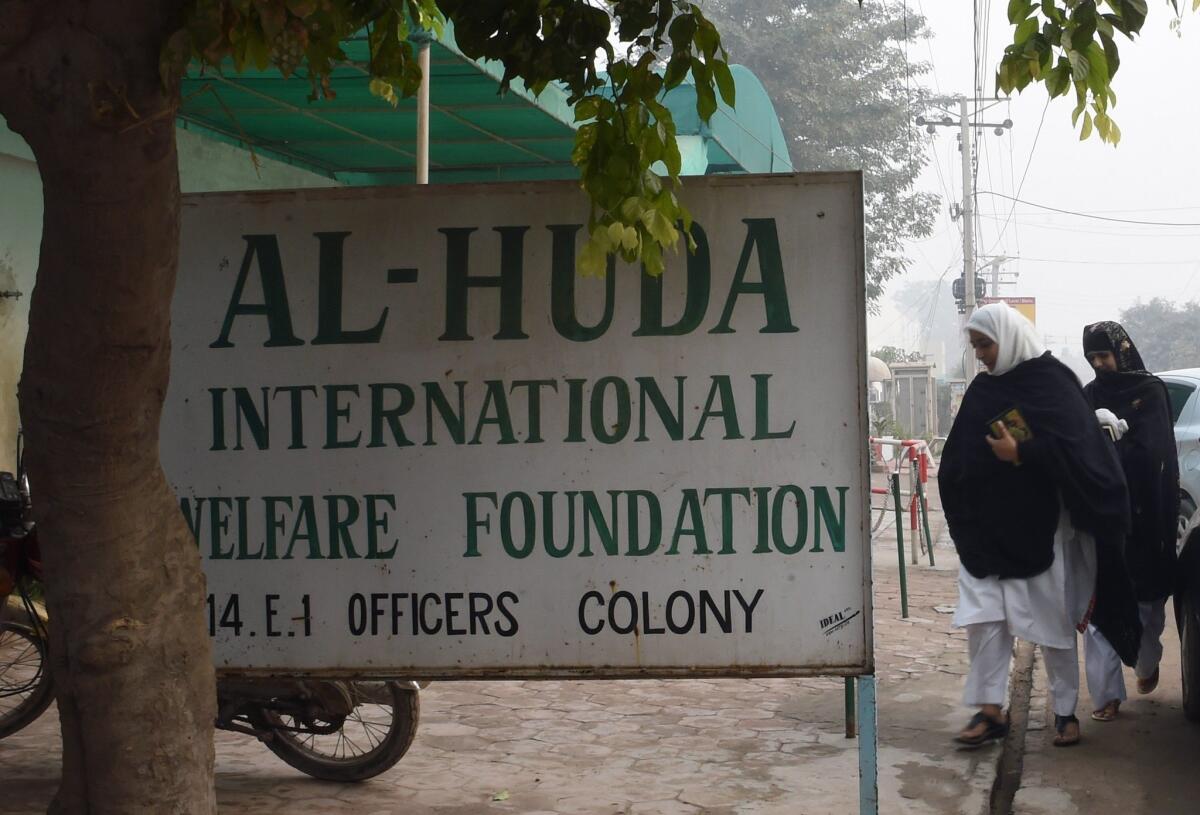

Pakistani students arrive at Al-Huda Institute, a seminary for women, in Multan on Dec. 8. San Bernardino shooter Tashfeen Malik studied with Al-Huda while living in Multan.

- Share via

Reporting from Islamabad, Pakistan — Pakistani security officials on Wednesday questioned teachers and students at the Islamic seminary that Tashfeen Malik attended in 2013 in an effort to trace the San Bernardino shooter’s path to radicalism.

Security personnel also searched the house where Malik was said to have lived in the central Pakistan city of Multan, where she attended a separate university from 2007 to 2013, a police official said.

“They have searched her house at Multan but so far have not found any clues that she was in touch with any extremist organization during her stay in Multan,” said the police official, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to discuss the investigation.

FULL COVERAGE: San Bernardino terror attack | Live updates

Representatives of the women’s seminary in Multan, known as Al Huda, said that teachers and students were interviewed for the first time Wednesday, four days after The Times first reported that Malik had attended the school.

“We have cooperated with them and provided them all the information,” an Al Huda representative in Multan said by phone. She declined to be named, citing a school policy.

Security officials in Islamabad said they had not yet found clues Malik had contact with extremist organizations during her time in Multan. Al Huda representatives said she began attending classes at the school in mid-2013 but dropped out after a few months.

Pakistani officials have said little publicly about the shooting that left 14 people dead at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino, suggesting that authorities would like to play down the suspects’ Pakistan connections.

Malik, 29, was born in Pakistan, raised in Saudi Arabia and was a U.S. resident. While studying in Multan she took classes at Al Huda, a women’s seminary that does not advocate violence but spreads a deeply conservative interpretation of Islam and, experts say, often inculcates students with anti-Western views.

The other shooter, Malik’s husband, Syed Rizwan Farook, 28, was an American citizen of Pakistani descent.

Following the assault in California, Pakistani authorities said they would launch a domestic inquiry, but officials have disclosed few details.

Pakistan has long been a problematic U.S. ally in the effort to combat terrorism, with a weak civilian government unable to monitor tens of thousands of Islamic schools, or madrasas, including some believed to preach violence. Pakistan’s military is also accused of tacitly supporting insurgent groups, including the Afghan Taliban and allies, that have attacked U.S.-led coalition forces in neighboring Afghanistan.

Al Huda is one of tens of thousands of private and Islamic schools scattered across Pakistan that operate largely without government oversight. Pakistan’s failing public education sector and widespread poverty have given rise to the madrasas, which take in mostly uneducated children of poor families and offer them free housing and religious education, but also include seminaries such as Al Huda, which caters to urban, upper-middle-class women.

Experts say it is impossible for the government to monitor these schools closely.

“There are a couple of million students studying at these madrasas,” said Imtiaz Gul, head of the Center for Research and Security Studies, an independent think tank in Islamabad, the Pakistani capital. “If one or two of them go astray and pick up guns – after living in America and being raised in Saudi Arabia – I don’t see any point for the Pakistani government to undertake any specific measures.”

A year ago Pakistan announced its intention to regulate and reform the madrasas as part of a 20-point national counterterrorism plan formulated in the wake of a massacre at an army-run school in Peshawar that left more than 132 children dead.

But the initiative has not gotten off the ground. Islamic clerics have resisted efforts to get them to register with the government, in part due to concerns over the forms they must fill out. As a result, the government still doesn’t know exactly how many madrasas are operating in the country or the sources of their funding.

Gul said that the lack of a uniform regulatory mechanism for the madrasas remains “a big failing of the state” but that Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s government – like others before it – is reluctant to confront powerful clerics.

“The government has vowed to do this, but as of now not enough is being done,” Gul said. “It’s simply a question of capacity and of political will. Most often the politicians do not take hard decisions [due to] electoral considerations.”

Estimates of the numbers of madrasas in Pakistan vary. An umbrella organization of madrasas counts 35,337 schools with nearly 3.5 million students. Pakistan’s government figures show barely more than 22,000.

There are thousands more, experts say, that are not registered with either body. But even if the government could count the schools, it would not have the capacity to monitor what’s being taught.

Ayesha Siddiqa, a Pakistani author and columnist who has studied Al Huda, says that while the privately funded institute is not believed to advocate violence, it sends students down the path toward more conservative thought and behavior that could tip into extremism. It would be difficult for authorities in Pakistan – or anywhere -- to determine exactly how a seminary student decided to commit a violent act, Siddiqa said.

“Just Tashfeen Malik’s case is not a strong enough basis to allow the government to force greater accountability on a random basis,” Siddiqa said. “You can’t go to Al Huda and say, ‘We want to know what you’re teaching.’ Even if they do that, it will be very difficult to pinpoint and say, ‘You shouldn’t be teaching this.’”

Pakistan’s reaction to the San Bernardino shooting has been muted as well because of an “image problem,” Siddiqa said: the perception that Pakistan is a haven for radicalism. Yet the vast majority of extremist violence emanating from Pakistan takes place domestically.

Some 60,000 Pakistanis have died since 2001 in militant attacks or battles between security forces and extremist groups, according to analysts. And while Malik and Farook reportedly pledged allegiance to Islamic State before the San Bernardino attack, Pakistan has not been a major source of foreign fighters for the extremist organization.

A report released last month said that of the estimated 25,000 to 30,000 fighters who have traveled to Iraq or Syria from foreign countries, about 500 came from Pakistan – fewer than from Britain, France or Germany.

“Every time there is some extremist incident that happens around the world, the first thing any Pakistani wishes for is, ‘Let there not be any Pakistani involvement,’” Siddiqa said. Part of the reason for Pakistan’s muted response to San Bernardino, she said, “is this ostrich feeling -- hide your head in the sand and ignore it.”

Special correspondent Sahi reported from Islamabad and Times staff writer Bengali from Mumbai, India.

Follow @SBengali on Twitter for news out of Pakistan

ALSO

Graphics: Where Muslims (mostly) don’t live

The San Bernardino shooter turned to a new type of online lending

From mockery to anger, world’s Muslims react to Trump’s call to keep them out

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.