From a bridge in South Africa, sidewalk bookseller believes in the power to change lives

- Share via

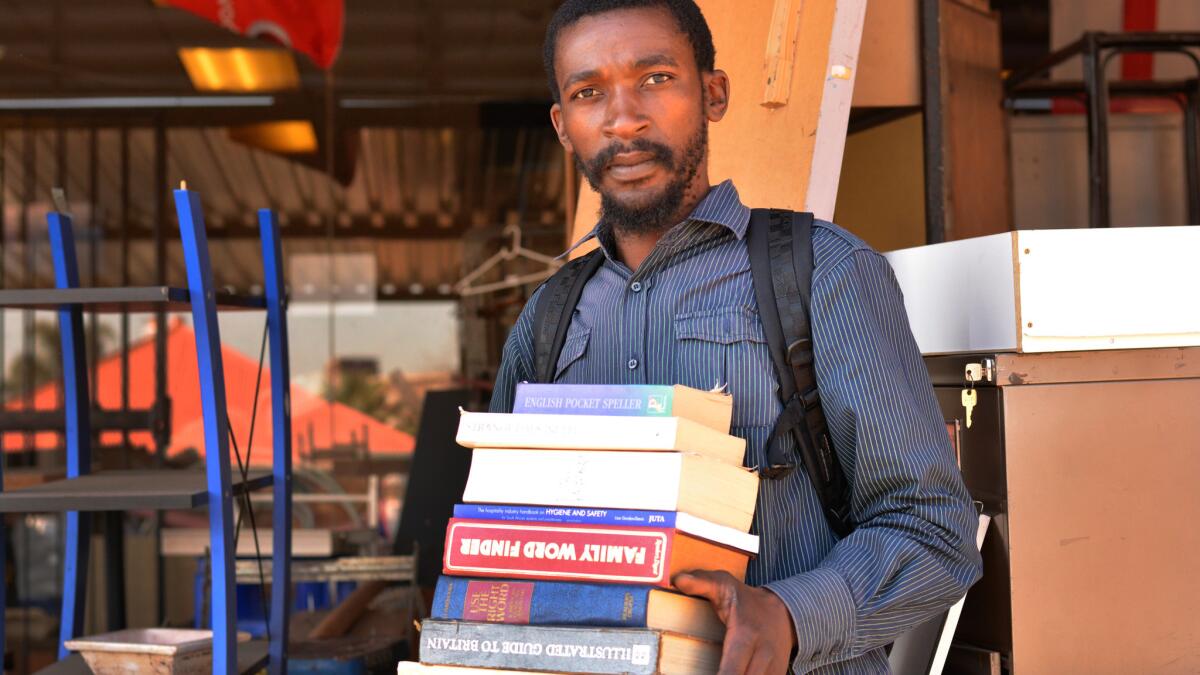

Reporting from Johannesburg, South Africa — He spends his day on his knees, reverently arranging and rearranging his books on the plastic sheets that serve as his sidewalk shop on a downtown bridge, as thoughtful as a fortuneteller turning over cards.

To Sandile Mavimbela, the books have more mystical pull than any deck of cards, and he believes in their power to change futures — including his own if he sells enough of them.

But they can also alter the lives of his readers. The span over a rail yard links two sides of a crowded, crime-racked city, but to him this place is a bridge from curiosity to knowledge.

“The concept is books are a bridge to a better life. I think you’re selling the knowledge, being a middle person between the customer and the book,” Mavimbela, 27, says.

The titles smile at the sky, willing readers to come. “Unfair Dismissal” by Andrew Levy, “Nedbank’s Money Making Made Simple” by Noel Whittaker, “The Hunger Games” by Suzanne Collins, “Boundaries: When to Say Yes, How to Say No” by Henry Cloud and John Townsend, “The Lord of the Rings” by J.R.R. Tolkien, “Heat” by George Monbiot, “Name Your Baby” by Lareina Rule, “The Art of Negotiation” by Michael Wheeler and “Lord Jim” by Joseph Conrad.

Customers bend over, browsing under the hot afternoon sun. Someone asks for a book about Thabo Mbeki, a former South African president.

“Orders can be difficult,” Mavimbela says, but he notes the title and customer’s name and phone number carefully in a large book. If he’s lucky, he might stumble across something the next time he visits one of the thrift shops he prowls for cheap books .

“One thing you almost always understand is that doing business on the street is never easy,” he says. “You have to do it your way so you get things right.”

An avid reader, he keeps back the best books to take home to read before he lays them out on the sidewalk to sell.

Today has not been lucky. There was the letdown at his favorite library, usually a good place to pick up cheap books, but barren after a recent clean-out of old titles. All he got was one out-of-print medical textbook, a good find, but not the usual treasure-trove.

“It’s hard to get good books,” he says.

He visits three thrift shops, where the white volunteers meet him with patronizing indifference or prickly hostility.

In the silence of a thrift shop in a wealthy suburb north of the city, Mavimbela groans in frustration as he peers through the titles.

His customers are always bugging him for dictionaries. Easy enough to find for wealthy buyers in new-book stores, they are hard to find secondhand.

He finally unearths two of the beauties, with “Oxford” in big shiny letters, from a box in the back. A friendly white woman named Judy always sells him good books for a few cents at this shop. But she’s away, and the elderly man in charge today is being, well, not so nice.

“Those books are for someone else,” the man snaps.

“Judy should have been here,” Mavimbela whispers, his face taut with disappointment. He leaves empty-handed.

At his next stop, classical music tinkles in the background as a row of murmuring black women sort through the secondhand clothing, surrounded by cricket bats, tennis rackets, suitcases, games, plates, curtains and shoes. Mavimbela runs a finger along the books, his eyes wistful. There’s not much here.

He asks the manager whether she has anything by American Christian novelist Francine Rivers.

“No, because they’re donated books,” she says with a patronizing laugh. “We don’t have a buyer.”

At another shop, where he has to pay 30 cents each for books people discard for recycling at 2 cents a pound, he hesitates over a thick tome on civil engineering hydraulics.

Will it sell? He ends up buying the book.

“Sometimes you get a nice book like this,” he says, picking up “The Naked Chef” by Jamie Oliver, like a fisherman hauling out a particularly fat trout. He’ll charge $2.50, a handsome profit.

Whenever the bookseller sees a book he likes, he taps the cover excitedly with his fingers and unconsciously huffs with exhilaration, tossing the book carefully onto a growing pile at his feet.

When the manager harangues him for searching through the boxes of discards, Mavimbela, studiously polite, avoids eye contact and flips through more.

Flip, flip flip. Tap, tap, huff.

Mavimbela pays $8.25 for his haul, careful to depart on good terms.

“They still have that mentality about blacks,” he says, “but I know what I’m looking for. I just choose to be quiet.”

He ends the day outside the thrift shop, as African street entrepreneurs sometimes do, sifting through the trash. “They always throw the good books out.” he says.

He pulls out book after book, flipping through the pages with slender fingers.

If it weren’t for books, Mavimbela’s life would have been an orphan’s path of crime, violence, alcohol and drugs.

His mother taught him: “Get up early, get a bath, look smart, be positive, do unto others as you would have them do to you.” By the time he was 6, he was selling steel wool pads in their small rural village on the border of Swaziland, where she was born.

“I knew I could sell things.”

But when he was 9, his father died of AIDS. His mother was ejected from the family home and returned to her homeland, leaving him to live with an aunt.

Mavimbela spent his days lying on his narrow bed, under which he had a pile of books and magazines he’d been given by the guards at a nearby border post.

“I guess I was depressed. I would not even go out to play,” he says. “I was so bored, I’d read anything.”

He went back to school the next year, but he was lonely and alienated and would drink several beers before class. He was drawn into cross-border drug smuggling, the area’s only real trade, and wound up in Soweto selling drugs to dealers.

“I didn’t have parents. It was only my own rule. I did what I wanted. Most of the time I’d hang out with the guys outside at night. Then the next morning, somebody was injured, somebody was stabbed, somebody was arrested.

“I realized I was the one destroying myself.”

He was sleeping rough on boxes in downtown Johannesburg before he met a man by chance who taught him the secondhand book trade. It reminded him of the childhood days. He found he had a talent for finding and selling the books people wanted to read.

He invests his earnings back into buying more books. Though he struggles financially, he makes enough for food and rent, and his customers promise to keep supporting his endeavor.

Buying a book is an act of hope, and Mavimbela understands his customers’ dreams: The school mothers looking for cheap textbooks for their children. The serious young people looking for motivational books on how to get rich. The older people seeking uplifting religious works. All his readers crave the one thing he has very little of: books by African authors.

Two young women wander by sheltering from the sun under an umbrella. Not far away, a team of shoe cleaners does a brisk trade. A man trundles past with a shopping cart, selling stuff he has “found.” A beggar, who smells as though he hasn’t washed in weeks, approaches Mavimbela, hand extended, and the book man reaches into his pocket for a bank note.

An old man leafs through one of Mavimbela’s books. A white tourist wanders by, taking photos of the skyline with his phone. Mavimbela purses his lips, afraid the visitor will fall victim to thieves. Locals typically stop such naive passersby, gently warning that there are “bad people” around and they’ll steal your camera or your phone for sure.

“Have you got dictionaries?” an earnest-looking mother of schoolchildren asks. A young woman with painted, pouty lips, tight jeans and blank dark glasses drifts up. She wants a nice book to read. She pronounces nice as “nahs,” breathing the word slowly from her lips. Mavimbela hops nimbly from one end of his pavement shop to the other, grabbing books, proffering suggestions.

A night of violence that shattered a South African’s view of her white privilege »

“The way I do it, I have to persuade, not in a persuading manner but a convincing manner,” he says. “I say this is just like what you are looking for. He wasn’t intending to buy that book, but he buys it anyway.”

The young woman buys several, looking pleased. Two other women find the textbooks they need.

There’s a thud nearby and a sudden silence. People freeze. A young man has been hit by a small truck, his body hurled into a shop window. The victim crawls to the side of the road, in slow motion. Women scream and clutch their heads. Men shout, “No!”

The young man is curled by the road, but no one calls an ambulance. “It will take too long,” an old woman says. Someone helps the man to his feet and he limps painfully to the truck that hit him, to go to a hospital.

Mavimbela thinks there must be a bad spirit haunting the bridge, reaping souls. Someone gets hit on the road every few weeks.

For a while, no one talks about anything but the accident. Slowly, people move on. Commerce starts back up. The shoe-cleaning guys tout for customers. Mavimbela arranges his books. And arranges them again. He strikes up conversations with customers, probing to find out what they like, and always producing something tempting.

Flip, flip flip. Tap, tap, huff.

The harsh percussion of the traffic, the whisper of flipping pages. This is the music of his days.

MORE WORLD NEWS

Bombed and beleaguered, a Baghdad neighborhood takes stock on a key Muslim holiday

Here’s why China refuses to block North Korea’s nuclear ambitions

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.