South African President Jacob Zuma resigns under pressure from ANC

South African President Jacob Zuma resigned, ending nearly nine years of rule marred by corruption scandals and fiscal mismanagement that inflicted serious damage on one of Africa’s biggest economies. (Feb. 14, 2018)

- Share via

Reporting from Johannesburg, South Africa — South African President Jacob Zuma bowed to intense pressure from his party and resigned Wednesday, ending nearly nine years of rule marred by corruption scandals and fiscal mismanagement that shamed the party of Nelson Mandela and inflicted serious damage on one of Africa’s biggest economies.

The 75-year-old leader’s approval ratings had been sinking along with those of his ruling party, the African National Congress. In the end, the party turned against him and sided with his deputy, Cyril Ramaphosa, who unseated Zuma as party president in December and now becomes acting president of the country.

The ANC National Executive Committee issued Zuma an ultimatum Monday: resign or be recalled from office.

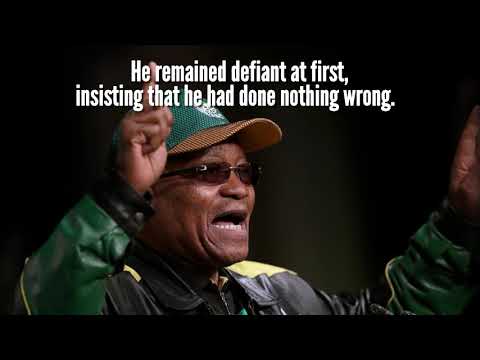

Zuma, who had already been resisting pressure from party leaders to quit, remained defiant at first. On Wednesday, he went on television and, in a lengthy statement, insisted that he had done nothing wrong.

He said he had asked ANC leaders what he had done wrong, but none could answer him.

“What is the rush? I have been asking this question all the time,” he told South African Broadcasting Corp. television. “You can’t force a decision as is being done now.”

“It’s the first time that I feel the leadership is unfair,” Zuma said. “It’s, ‘No, you must just go.’ The ANC does not run things that way. It’s a kind of ANC that I begin to feel that there’s something wrong here.”

But late Wednesday, Zuma backed down and in a television address announced his decision to resign.

“I do not fear exiting political office,” he said. “However, I have only asked my party to articulate my transgressions and the reason for its immediate decision that I vacate office.”

He insisted the decision to dismiss him was unjustified, but said he decided to resign in order to avoid violence between members of the ANC.

“I am forever indebted to the ANC, the liberation movement I have served almost all my life,” he said. “I respect each member and leader of this glorious movement. I have served the people of South Africa to the best of my ability. I am forever grateful that they trusted me with the highest office in the land.”

Ramaphosa, now the acting president, is expected to be elected president at a meeting of the ANC parliamentary caucus in coming days.

Zuma had been due to leave office when his term ended in 2019. But Ramaphosa and his supporters wanted Zuma out well in advance of next year’s presidential election in hopes that the ANC would have time to rebuild its support.

The opposition Democratic Alliance had said any departure deal should be made public and threatened to go to court if Zuma was given immunity from prosecution on corruption charges he is trying to fend off.

Zuma rose to power on the important role he played in the struggle against apartheid and on his charisma, often rousing party supporters, dancing and singing his trademark apartheid-era struggle song, “Bring Me My Machine Gun.” He ended a depleted figure, booed at party gatherings.

His method of governing — using the law to go after enemies, and state contracts and government jobs to enrich allies — is common in many African countries. But many South Africans, including sections of the ANC, were horrified at the scope of the scandals that followed him.

Soon after taking office in 2009, Zuma upgraded his mansion in the coastal province of KwaZulu-Natal, charging the state for “security upgrades,” including a swimming pool, a visitor’s center and an amphitheater. He was eventually forced to pay back $600,000 to the government.

Less than a year into his presidency, family members and friends had accumulated scores of companies, getting rich on the patronage that his political machine lavished.

Lawmakers and government officials have alleged that a powerful business family used its friendship with the president to manipulate Cabinet appointments. Critics say the Gupta family — which has joint ventures with one of Zuma’s sons, Duduzane Zuma, and has employed two other Zuma family members — “captured” the state in an effort to advance its commercial interests, which include mining, media and aviation.

The family and Zuma have denied the allegations.

In a sign that the political winds have shifted, a police anti-corruption unit known as the Hawks raided the home of the Guptas on Wednesday. The Hawks confirmed three arrests had been made and said two other people had agreed to hand themselves over to police.

The arrests related to a dairy farm project in Free State province that was supposed to direct money to poor black South Africans. Instead, almost all the money is alleged to have been used to pay for a Gupta family wedding.

Under Zuma, many of the people shuffled into government jobs were unqualified, ill-equipped or corrupt. He drew widespread criticism in 2016 when he dismissed a reputable finance minister, Nhlanhla Nene, and tried to install a former mayor of a small municipality with little experience in finance.

That same year, a Chinese rhino horn trafficker said in a television documentary that he “did business” with the wife of David Mahlobo, a former state security minister and close Zuma ally. He said Mahlobo was his friend and displayed cellphone photos of them together.

Mahlobo denied either he or his wife had any connection with the trafficker and was never investigated. He remains in the cabinet as minister for energy. Zuma had been promoting a controversial $83-billion nuclear power plan that Ramaphosa says the country cannot afford.

The proposed nuclear deal with Russia was pushed hard by Zuma and Mahlobo, with critics accusing the government of undue haste in pursuing the agreement.

Zuma was tainted by scandal even before voters elected him. He had been accused of rape, then acquitted, and charged with making over 783 corrupt payments as deputy president before prosecutors dropped the charges weeks before the 2009 election, clearing his way to become president after the vote.

But, popular in the party, he overcame the political damage from those episodes with a personal story that made him a hero in the fight against apartheid.

He grew up illiterate, forced to herd cattle as a child instead of going to school, after the death of his father, a policeman. His mother left him in the care of relatives and went to the city of Durban to earn money as a maid, and he began to teach himself to read, using other children’s schoolbooks.

He joined the ANC in 1959 and was jailed for 10 years on Robben Island with Mandela, who went on to become the nation’s first black president. Zuma never received a visitor; his mother was too poor to travel to see him.

Upon release, he rose through the ranks of the ANC to head the intelligence arm of its military wing.

His history and his outsized personality propelled him to the leadership of the party. He was a populist who exuded charm and warmth, unlike former President Thabo Mbeki, the cool and remote successor to Mandela.

The pressure for Zuma to step aside began to mount last fall after a court ordered the reinstatement of corruption charges that had been dropped in 2009 — a decision he is now fighting — and the deepening scandals over the influence of the Gupta family.

Increasing that pressure were the effects of fiscal mismanagement.

Last year, global credit rating agencies downgraded South Africa’s debt rating to junk. State-owned enterprises piled up debt, requiring repeated bailouts. Recently the finance minister warned that electricity provider Eskom was in such bad shape that it could topple the entire South African economy.

Zuma lost control of the party at a national conference in December, failing in a bid to ensure his ex-wife, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, succeeded him, an effort many viewed as designed to shield him from prosecution.

Instead Ramaphosa narrowly won the presidency of the party and the right to succeed Zuma as the nation’s president if the ANC wins parliamentary elections next year. In South Africa, the majority party in Parliament elects the president.

Zuma also lost control of the ANC’s National Executive Committee, the only party body with the power to fire him — or in the parlance of the party, “recall” him.

Ramaphosa had started turning against his boss last year, telling a radio interviewer that he believed the president was guilty of rape, despite his 2006 acquittal.

At the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, last month, Ramaphosa said that South Africa had been captured by corrupt elements close to Zuma.

As the sense of crisis deepened, the national currency surged at every suggestion Zuma would go.

His decision to resign saved the ANC the embarrassing spectacle of voting with opposition parties in Parliament to oust him. The party had supported him in past no-confidence votes.

Zuma had been scheduled to deliver the state of the nation speech to Parliament last Thursday. The address will now be delivered by Ramaphosa on Friday evening, after he is elected president that morning, the ANC has said.

After several days of negotiations between Ramaphosa and Zuma, the party’s executive committee met in a marathon 13-hour session Monday to decide the issue. A letter of recall was delivered to Zuma by the party Tuesday.

Zuma is not the first South African president to be forced out of office. In a power play orchestrated by Zuma supporters, Mbeki resigned in 2008 after he was “recalled” by the executive committee, nine months before his term was due to end.

Many hope that Ramaphosa will clear out corruption in the ANC by appointing a strong chief of the National Prosecution Authority and empowering that person to go after powerful figures in the party — even at the risk of losing some key political allies.

Twitter: @RobynDixon_LAT

UPDATES:

2 p.m.: This article was updated with details of Jacob Zuma’s resignation speech.

This article was originally published at 1:05 p.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.