Philippine president’s swagger recedes in the face of a powerful China

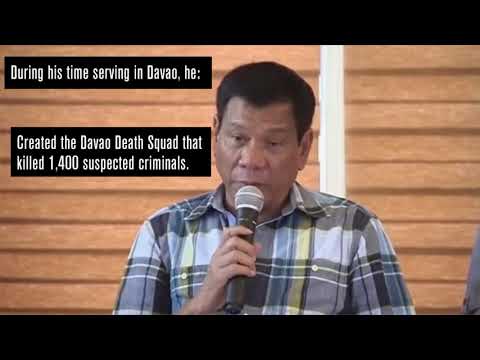

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, 71, passed his 100th day in office on Oct. 8.

- Share via

Reporting from MANILA — When he was campaigning for the presidency last year, Rodrigo Duterte spoke with swagger about how he’d handle China’s claims to Philippine territory in the South China Sea.

“I will ride a jet ski and plant the Philippine flag there in their port,” Duterte said.

Now that he’s president of the Philippines, Duterte still speaks brashly about many things. But when it comes to China, the preeminent Asian superpower, he has toned down the rhetoric substantially, while still trying to assert his country’s sovereignty over its territory.

It has not been an easy balancing act.

Duterte ordered his military in April to occupy the contested Spratly Islands in the South China Sea — a bold assertion in the face of Chinese claims to the islands.

“We tried to be friends with everybody but we have to maintain our jurisdiction now, at least the areas under our control,” the presidential office website quoted Duterte as saying at the time. “And I have ordered the armed forces to occupy all — these so many islands, I think nine or 10 — [to] put in structures and the Philippine flag.”

But China has the world’s third most powerful military; the Philippine armed forces rank No. 51, according to the database GlobalFirePower.com. Pressure from China caused Duterte to retreat within weeks, opting instead for a maritime strategy intended to keep approval ratings high at home while preserving peace with Beijing.

After China voiced “concern,” Duterte said his government would improve structures on the islands, but not deploy weapons. It was not the first time he had made concessions to China.

Duterte set aside differences with Beijing in October to diversify foreign policy away from heavy reliance on the United States and to avoid conflict in the South China Sea. Beijing pledged $24 billion in aid and investment for the Philippines that month. This month, the two countries opened talks on how to manage competing claims to the resource-rich tract of water between them.

China is waiting for Duterte to take a consistent stance on the Spratly Islands, said Yun Sun, a senior associate with the East Asia Program at the Stimson Center, a Washington-based think tank. The communist leadership may be unsure how to read Duterte’s comments and hopes to avoid a confrontation, analysts say.

“After securing the friendship with the Philippines, I don’t think the Chinese are so stupid to just unfriend the Philippines,” said Eduardo Araral, associate professor at the National University of Singapore’s public policy school.

Still, China has proved determined to cement its claims in the South China Sea. It claims more than 90% of the 1.4-million-square-mile body of water, overlapping the claims of five other countries, including the Philippines.

Philippine fishing boat operators have griped about Chinese control over Scarborough Shoal, a South China Sea feature coveted for its catches, since a standoff there in 2012. The issue prompted Duterte’s predecessor to seek world court arbitration, which went against Beijing in July 2016.

“We cannot go to Scarborough Shoal anymore because of the Chinese patrol. They’re roving,” said Butch Ortega, 42, a fisherman of 20 years from the South China Sea coastal town of Masinloc, north of Manila.

In March, Filipinos objected in the legislature and through opinion surveys after Philippine news reports said Duterte knew Chinese vessels had parked at Benham Rise, an undersea plateau off the Pacific coast of the largest Philippine island, Luzon. One ship was stationed there for three months in 2016, the reports said.

The United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf had approved the Philippine claim to Benham Rise in 2012 and the country is considering exploring the 32-million-acre plateau for gas and minerals.

An opposition political party cited the Benham Rise case in March as a “betrayal” of the public and added it to an impeachment case — so far feeble — against Duterte.

“That sort of touched a nerve with the public and focused attention on his foreign policy vis-a-vis China,” said Jay Batongbacal, director of the Institute for Maritime Affairs and Law of the Sea at the University of the Philippines in Quezon City. “He needs to show the public he’s doing something about this.”

Duterte’s performance rating fell from 83% to 78% from December to March, according to the Philippine polling service Pulse Asia Research.

Since the world arbitration court said in July that Beijing lacked a legal basis for claiming much of the South China Sea, Chinese officials have sought one-on-one talks with the other claimant countries to work out differences.

China has pumped tourists into Vietnam, a normally outspoken maritime rival, and invested heavily in two others, Brunei and Malaysia.

China is unlikely to claim Benham Rise or build there, but it may have its sights on the plateau as part of a submarine route from its Hainan province west of Hong Kong to the Pacific Ocean, Araral said.

“Whenever China sends its exploration ships, there’s always doubt about what is China up to,” he said. “But in the case of Benham Rise, it is not a place where it can build artificial islands.”

Chinese could technically revoke last year’s aid pledges to the Philippines since most of it has not materialized yet. It could also stop Philippine fishing boats throughout much of the South China Sea during a May-August fishing moratorium that Beijing has imposed.

Beijing may hold off on any retaliation unless Duterte invites the U.S. Navy back for joint South China Sea patrols, giving the Philippines a boost in military might, Yun said. In mid-May the two navies held exercises off the Philippine coast near Benham Rise but avoided scenarios related to the South China Sea.

“I think the Chinese were prepared for this type of reversal of the Philippine position,” Yun said of Duterte’s remarks since early April. “Duterte’s comment is not always consistent.”

The Philippine president thundered last year against the United States for its criticism of extrajudicial killings of suspected drug dealers since he took office in June and demanded a reduction in U.S. military aid.

But his government and the United States, a Philippine colonizer for five decades until 1946, have retained a 1999 visiting forces agreement and a 2014 agreement that lets U.S. troops rotate in and out of the country.

In any event, if Duterte can stick to his plans for the Spratlys and keep China away from Benham Rise, he should maintain his high approval ratings at home, analysts said. “President Duterte is very much trusted with the Philippine people,” Araral said.

ALSO

China’s Belt and Road Forum lays groundwork for a new global order

In the Philippines, poverty and corruption fuel the drug trade

Jennings is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.