Many Hong Kong parents just don’t understand student-led protests

- Share via

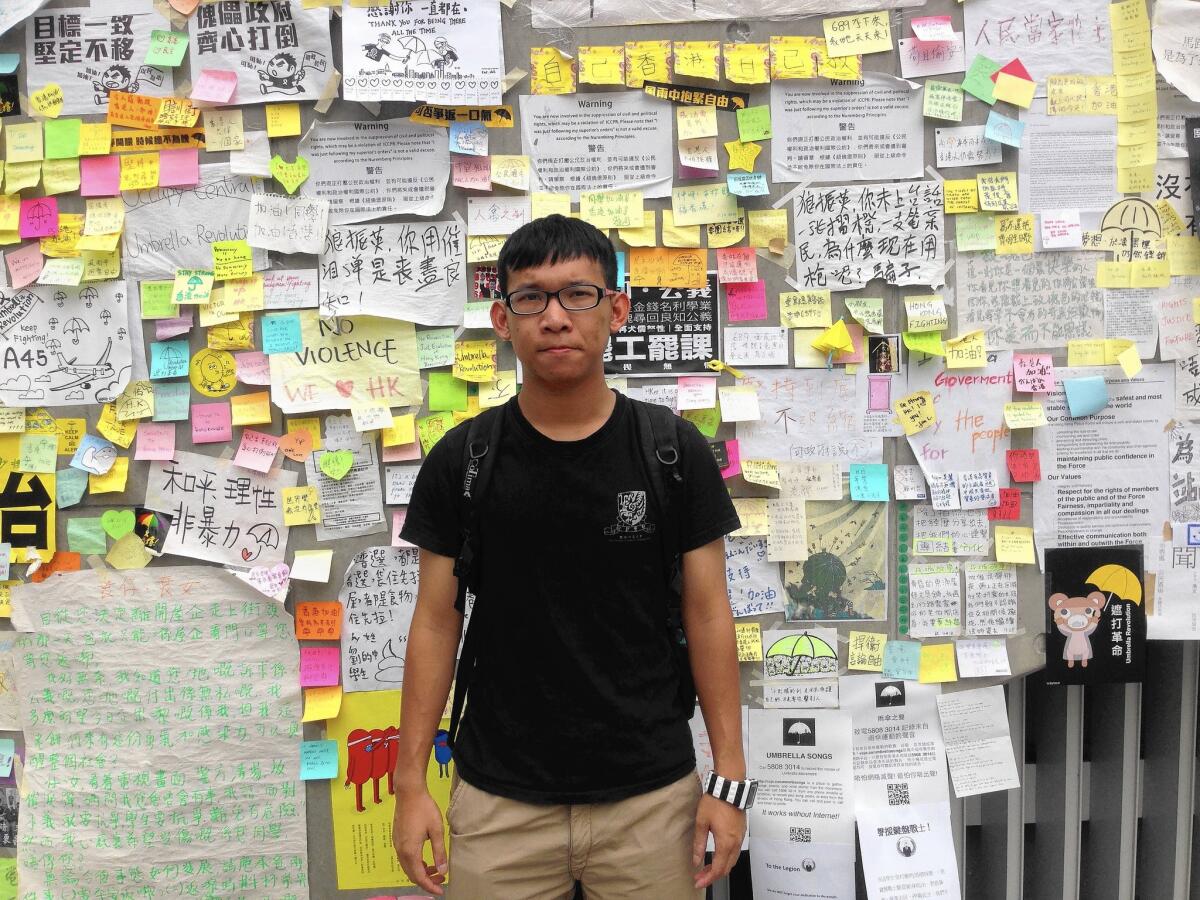

Reporting from Hong Kong — Every time Kelvin Chan returns home around midnight from the daily pro-democracy rallies here, he finds his father fuming silently in the living room.

“He says nothing when I come in,” said Chan, 23. “He just gets up and goes to his bedroom.”

When Chan tries to broach the subject of freer elections, the patriarch is intractable, convinced his son is jeopardizing the young man’s future and meddling futilely in Chinese politics.

“It’s tearing apart our relationship,” the recent college graduate said.

Like many young protesters who have taken to the streets, Chan is struggling to bridge a generational divide freshly exposed by more than two weeks of polarizing demonstrations.

On one side are students and recent graduates whose democratic aspirations are seasoned by the growing competition for university placements, jobs and ever-more expensive apartments because of the influx of mainland Chinese.

On the other side are parents, often pragmatic first- or second-generation immigrants from the mainland who prize stability above all and see little hope, let alone use, in challenging Beijing’s authoritarian rule.

“This group in their late 40s or 50s witnessed the June 4 Tiananmen massacre and are inculcated with a deep sense of political powerlessness,” said Dixon Ming Sing, associate professor of social science at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, citing the 1989 crackdown on protests in the Chinese capital. “They think that Beijing is such an economic giant that it’s really difficult, if not impossible, for them to move an inch in terms of further democratization.”

The younger generation, on the other hand, has seen how mass activism successfully blocked two attempts by China to diminish some of the territory’s autonomy: the 2003 defeat of an anti-subversion bill known as Article 23 that would have eroded freedom of speech, and resistance in 2012 to a proposal for so-called patriotic education in schools that critics said was an attempt to brainwash children into loving China.

Ever since Britain returned Hong Kong to China in 1997, the territory has operated under a framework known as “one country, two systems” that preserved democratic freedoms. And although Hong Kong citizens were never permitted to choose their colonial governor, they were supposed to be allowed to directly elect the territory’s chief executive beginning in 2017.

Then in August, China’s legislature announced that the chief executive would be chosen from a slate of candidates screened by Beijing, sparking the current demonstrations. “Even if we were still under the British, we would fight for the right to vote,” Chan said.

Experts agree there is little hope of Beijing opening elections to a popular vote. Hong Kong Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying reiterated that point this week in an interview with a local broadcaster, saying there was “almost zero chance” of Chinese leaders changing their stance.

The protests are being led by three main groups: Occupy Central With Love and Peace, headed by two professors and a Christian minister; Scholarism, a group of high school students; and the Hong Kong Federation of Students, which is made up of college students.

Pessimism in Hong Kong’s future skews young. A Hong Kong University poll released last month showed that only 11% of respondents ages 18 to 29 had confidence in the “one country, two systems” policy. By comparison, 52% of respondents 50 or older said they were confident in the system.

Part of that gulf in opinion can be explained by changes in geopolitics since the Tiananmen crackdown 25 years ago, said Jeffrey Wasserstrom, an expert in Chinese history at UC Irvine.

“When the older generation in Hong Kong looked at their regional neighbors in 1989, there was a right-wing authoritarian regime in Taiwan and a right-wing authoritarian regime controlling South Korea,” Wasserstrom said. “There seemed to be a lot of variations of one-party rule. And now young people are seeing how the most modern and exciting cities tend to be ones where people have the right to vote and seem to be doing very well.”

The discontent isn’t purely political. Hong Kong’s youths are stepping into a far more competitive environment than their parents’ generation.

Up to 10% of undergraduates at local universities and more than 60% of graduate students now come from the mainland, leaving fewer places for natives.

Many Hong Kong graduates complain that the mainlanders also have a distinct advantage in the hunt for jobs because so much business is conducted in China. Command of Mandarin, not the Cantonese dialect of Hong Kong, is essential.

Meanwhile, homeownership moves further out of reach. Housing prices have hit record highs in the territory of 7 million, in no small part because of the deluge of mainland money pouring in.

“Upward mobility has been constricted,” said Sing, the social science professor.

Amanda Hui, 48, agrees that young people are facing more pressure. But she thinks the disruptive sit-ins will only alienate politically moderate residents like her.

“It’s total chaos,” said Hui, a stay-at-home mom walking past an intersection occupied by protesters in the Mong Kok district. “I’ve never seen anything like this in Hong Kong. They should leave. Even if all of Hong Kong decided to protest, it wouldn’t change Beijing.”

To Mabel Chung, abandoning the protests is unthinkable, even though her parents strongly disapprove of the challenge to Beijing. The 20-year-old Chinese-language and literature major at the Chinese University of Hong Kong has been camping out at the main demonstration site in the Admiralty district for about a week.

Her father, a construction worker and People’s Liberation Army veteran who immigrated illegally to Hong Kong from the mainland in the 1970s, told Chung that she was naive to believe she could make a difference in the territory’s future.

“I mostly just try to avoid talking to them about it,” Chung said.

Despite heaving in agony Sept. 28 when police deployed tear gas, she has stuck with the sit-in and has come to cherish its utopian atmosphere. Protesters offer dim sum to passersby. Public restrooms are chock-full of donated toiletries. Students offer free tutoring to one another and build desks along a highway median to use for studying.

“I’m scared, but I feel like I’m doing the right thing by being here,” said Chung, who sleeps on a plastic bag splayed out on the ground and uses her backpack as a pillow.

Trevor Yeung, who tries to squeeze in a few hours each day at the Admiralty sit-in after work, hasn’t been able to avoid confrontation with his parents.

One morning, while the three were eating breakfast at a restaurant, Yeung’s father said, “Look at how these stupid students are stopping everything in Hong Kong and hurting the stock market.”

Yeung, who had kept his emotions bottled for days, shot back, “What if your son is one of those stupid people?”

The relationship has been cool ever since. Yeung, a 26-year-old artist, reminds himself his parents are not college-educated and have not traveled the globe, as he has done.

“I don’t know how to talk to them about this,” Yeung said. “They’re not politically active. I can’t just stay at home looking outside. I need to participate. I want to help.”

Special correspondent Nicole Liu in Hong Kong contributed to this report.

Twitter: @dhpierson

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.