‘Brexit remorse’ is fading, which is why Britain’s upcoming election could be very good for the Conservatives

- Share via

Reporting from London — For the first time since she first became eligible to vote more than five decades ago, Barbara Hague is planning to place a cross in the box beside the Conservative Party candidate in Britain’s upcoming election.

Despite wishing to stay in the European Union during last year’s June referendum and voting Liberal Democrat most of her life, she is putting her trust in Prime Minister Theresa May to lead the country as it severs its decades-long ties with the 28-member bloc.

“I feel this election is all about ‘Brexit’ and although I voted to remain, the country voted to leave. We have got to go along with that,” said Hague, a retiree from Barnet, in north London. “I feel Theresa May is the best person to lead us through it, but she needs a big majority.”

Analysts predict that voters like Hague will not be unique in the June 8 election, which is shaping up to be unlike any other in recent memory. Traditional party allegiances are being cast aside in favor of candidates the electorate believes can best steer the country through two years of fraught divorce negotiations, a process that has colloquially become known as Brexit.

This does not, however, mean the country is any less divided about the referendum, in which 52% of voters chose “Leave” and 48% opted to “Remain.”

“People are not necessarily changing their views about Brexit,” said polling expert John Curtice, a senior fellow at the UK in a Changing Europe think tank. “What they are changing their minds about is how to express their views about Brexit with respect to their party political choice.”

In the days and weeks following the June 23 referendum, there were reports of so-called Brexit remorse.

As the pound sterling initially fell sharply against the dollar, viral videos circulated of voters saying they backed “Leave” but didn’t actually expect their side to win, and wanted a do-over.

Polls show that those attitudes have not withstood the test of time and most people would vote the same way again tomorrow, given the chance.

“I think people were generally pretty surprised by the results, but I haven’t seen any evidence of buyers’ remorse among Remain or Leave voters,” said James McGrory, co-executive director of Open Britain, the successor to the referendum’s Remain campaign. It is calling for a softer version of Brexit than May is currently proposing and the maintenance of close ties with Europe.

McGrory attributes this lack of an attitude shift to the fact that Brits have not yet seen enough of the negative consequences of leaving the European Union.

Inflation has risen, the pound has weakened, but the doomsday scenarios painted before the referendum by economists and campaigners have not materialized.

Now that the clock is running on ‘Brexit,’ here’s what you need to know »

“We are still in the EU, the negotiations haven’t even started. Article 50 was only triggered at the end of last month. A lot of the doubts are the same,” McGrory explained.

“Leave campaigners and the government are still promising people that Brexit is going to be a relatively cost-free option. They are still claiming that on Day One when we leave there will be all these fantastical trade deals with India and China. My own view is that this stuff is going to be very difficult to deliver.”

Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty is the formal process that begins the unraveling of decades of complex, intertwined laws and regulations between Britain and the rest of the EU.

May set it in motion with a letter hand-delivered to European Council President Donald Tusk at the end of March, but official talks with EU leaders will not begin until after the election.

That makes her decision to hold an election now all the more shrewd.

“She’s calling an election before the really negative headlines start to dominate the news with the negotiation outcomes,” said Jane Green, professor of political science at the University of Manchester.

Early polls suggest that May does have a commanding lead as she peels off voters from the far-right UK Independence Party, which campaigns on a staunchly anti-EU platform while simultaneously winning over some Remain voters, like Hague, who are now resigned to the fact that Brexit is happening, and believe May is the best chance they have to get a good deal.

May is also trying to make this election all about her ability to provide “strong and stable” leadership during a time of turmoil, a phrase she repeats at every interview and election rally.

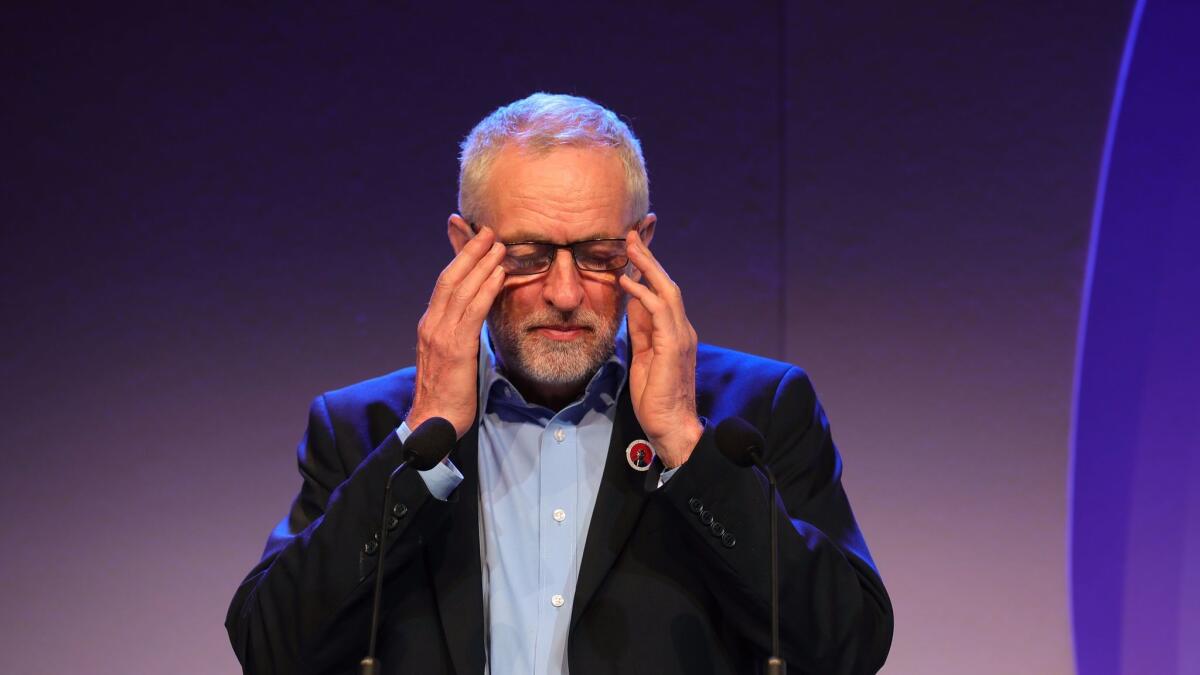

With this mantra, she is shining a spotlight on the other key factor in her favor right now: the opposition Labor Party’s disarray.The Labor Party became bitterly split during the referendum, with many thinking its leader, Jeremy Corbyn, ran a lackluster campaign for the Remain side.

Many of the Remain camp’s worst results were in working-class, traditional Labor heartlands in the north of England. And many of those voters are planning to abandon the party in the upcoming election, polls show.

Since last June, Labor has failed to prove it can provide unified, decisive leadership or offer a viable alternative to the “hard Brexit” that May is proposing — which could involve Britain leaving both the European single market and the customs union in order to regain control over key issues such as immigration and laws.

This is why Corbyn is on the campaign trail talking about the faltering national health center, welfare cuts and a housing crisis — in other words, anything but leaving the EU.

The only mainstream party that is standing up for the Remain camp in this election is the Liberal Democrats, who would like to stop Brexit, but advocate a more moderate version of the breakup if it can’t be blocked.

The centrist party, which focuses on social inequality and seeks greater European integration, says it has signed up 12,500 new members since the election was announced and raised more than $650,000 from grass-roots supporters.

“I think the Liberal Democrats’ fundamental role is to hold Theresa May to account, but to keep the flame alive for a pro-European outcome in the future,” said green entrepreneur Charles Perry, who took to the streets of London along with tens of thousands in the days after the vote to express his dismay with the referendum result.

The Liberal Democrats hope they can translate this membership surge into some key parliamentary seats on June 8, but the electoral system has not worked in their favor in the past.

If their supporters are spread too thinly around the country, having more votes could fail to translate into seats in the House of Commons because of the way the British electoral system works. The electorate does not vote directly for prime minister, and parties are assigned seats in Parliament based on local results for each candidate, not an overall percentage.

That is why Open Britain has published a list of Brexit-supporting members of Parliament they hope to oust to focus the electorate’s attention on key seats that could alter the electoral map.

Perhaps one of the ironies in this whole saga is that May herself campaigned — reluctantly, many say — alongside her predecessor, David Cameron, for the losing Remain side.

Now she is not only the one responsible for triggering Article 50, but doubling down and calling an early election to try to make sure that nothing hampers her ability to achieve Britain’s complete independence.

In several interviews shortly after becoming prime minister in the wake of the referendum vote, May ruled out calling an election before the current parliamentary term expires in 2020. But so far there is more focus on her reputation as a stable, safe pair of hands than her U-turns.

“Trying to pin down Theresa May is not an easy exercise,” said professor Tim Bale, who teaches politics at Queen Mary University of London. “She is rather an eclectic mix of various strains within the Conservative Party. On the one hand quite socially progressive, especially on women’s issues. On the other hand she seems to be very hard-line when it comes to immigration.

“She’s managing to be all things to all people,” he added. Polls have been notoriously inaccurate in the last year, but if May’s gamble is right and she not only wins but strengthens the size of her majority in the House of Commons, it will unquestionably place her in a commanding position as she navigates the years ahead. She also hopes it will keep the lid on any Brexit naysayers.

“In some ways it does make Brexit absolutely inevitable now,” Bale said. “I don’t think there’s any way back after this election.”

Christina Boyle is a special correspondent.

ALSO

European Union leaders may welcome a united Ireland after Britain’s departure via Brexit

Meet the man who could become France’s youngest president

Lawmakers in Scotland back referendum on independence from Britain

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.